|

Back

Enchantment Penetrates My Senses Berlin

Deutsche Oper

09/20/2009 - & September 26, October 1, 2009, January 31, February 12*, 2010

Richard Wagner: Tannhäuser

Stephen Gould (Tannhäuser), Reinhard Hagen (Landgraf Hermann), Petra Maria Schnitzer (Venus/Elisabeth), Dietrich Henschel (Wolfram von Eschenbach), Clemens Bieber (Walther von der Vogelweide), Lenus Carlson (Biterolf), Jörg Schörner (Heinrich der Schreiber), Jörn Schümann (Reinmar von Zweter), Martina Welschenbach (Shepherd)

Orchestra, Chorus, and Extra Chorus of the Deutsche Oper Berlin, Ulf Schirmer (conductor)

Bernd Damovsky (set, costume, and lighting designer), Silvana Schröder (choreographer), Kirsten Harms (production)

(Courtesy Deutsche Oper Berlin)

Deutsche Oper Berlin is reviving up for the forthcoming Wagner bicentennial in 2013. Since November it has been presenting “Wagner Festival Weeks” featuring five of the composer’s mature works and the house’s first ever production of Wagner’s earlier opera, Rienzi. In addition, in April the company will revive its well weathered post-modernist production of Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung, a much anticipated event that has long since sold out. Only Parsifal is missing from its repertoire this season.

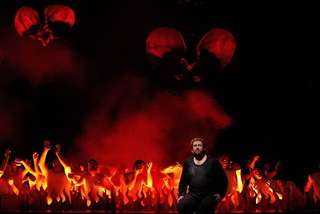

Kirsten Harms’s production of Tannhäuser premiered in November 2008. Featuring the opera’s earlier and now less commonly performed Dresden version (without the first act ballet added for the scandalous Paris premiere of 1861), Harms’s effort draws us into the realms of fantasy and the unconscious. As the overture plays, a stunt double of Tannhäuser is lowered from above the proscenium into watery depths, where topless bubble blowing nymphs greet him with stylized dance movements and a ritual undressing. He is descending into the Venusberg – the eternal feminine’s realm of desire and eroticism, everything he, and we, are supposed to suppress to conform to phenomenal reality and the expectations of a society that tells us at some level to fear. Indeed, Tannhäuser’s spiritual emptiness within the Venusburg and abrupt departure from it leave him confronted with the graphically depicted consequences of sin. In Harms’s production the chorus of pilgrims is not blithely wandering toward Rome, but, thanks to an effect of the Deutsche Oper’s stage elevators, already burning in Hell and singing hopefully of redemption from within its fiery embrace. Winged demons circle above. Conventional society quickly appears in the form of the Landgrave and his knights, all in traditional if rather cumbersome suits of armor, bearing lances astride artificial horses led about by pages.

Convincing Tannhäuser to return to them without dismounting – without descending to his level – we are ushered into the realm of the Wartburg, the respectable, if oppressive, bastion of courtly propriety that serves as the antithesis of the Venusburg. Elisabeth’s ecstatic second act aria, an apostrophe to the castle’s famous Singer’s Hall (here an open space filled with regimented suits of armor that rise and remained suspended over the rest of Act II) and exultation at news of her beloved Tannhäuser’s return, gives us a major psychological insight into the work – that Venus and Elisabeth are really two aspects of the same eternal feminine who comprise the idea of woman in all its complex totality. By casting the same singer as Venus and Elisabeth, this production reinforces that idea. In the final act Elisabeth’s death after her prayer and sanctification by Wolfram’s Evening Star song leave her body on stage. When the embittered Tannhäuser returns from his failed pilgrimage to receive the Pope’s forgiveness for his descent into the Venusburg, she rises, reanimated as the goddess in what appears in this production to be a successful attempt to lure him back into her embrace. Salvation, then, can be found as integrally in Eros as it can be in the dimensions of Christian piety.

The evening proved that hearing Wagner in Germany can be an experience without parallel. It is pointless to say that Stephen Gould is no natural Heldentenor, for the more lyrical qualities of Tannhäuser’s music do not require the heft of later Wagnerian heroes. Gould never lacked volume or intensity and only seemed to grow in power over the course of the evening. Tannhäuser’s bitter third act monologue was absolutely riveting. Petra Maria Schnitzer expertly took on the dual role of Venus and Elisabeth and managed the balance well. Her ruthlessly seductive Venus scenes alternated impressively with her Elisabeth’s charming adoration and wise caritas. A cool, smooth tone complemented intelligently articulated ascents. Dietrich Henschel’s Wolfram, though dramatically appealing, suffered from a huffy quality that undermined the part’s psychological depth and emotional sensitivity. His song to the evening star emerged as his best singing, but it lacked the symbolic insight that might come with the realization that the evening star is in fact Venus. Reinhard Hagen’s sturdy bass fared far better in the role of Landgrave Hermann. Clemens Bieber, Lenus Carlson, Jörg Schörner, and Jörn Schümann were adequately gruff in their brief appearances as the Landgrave’s retinue and fellow contestants in the song contest.

Ulf Schirmer led the Deutsche Oper Orchestra with finely disciplined attention and admirably expressive tempi that delicately navigated between the temptations of moving too fast or too slow. The company’s chorus and expanded chorus delivered with verve and excitement. The Pilgrim’s Chorus in Act III, delivered from hospital beds, resounded as such a model of Wagnerian choral singing that one could rightly wonder why the composer later decided that employing a chorus is not aesthetically correct.

Paul du Quenoy

|