|

Back

Giovanni the Narcissist Toronto

Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts

02/02/2024 - & February 4, 7, 9, 15, 17*, 24, 2024

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Don Giovanni, K. 527

Gordon Bintner (Don Giovanni), Mané Goloyan (Donna Anna), Anita Hartig*/Charlotte Siegel (Donna Elvira), Ben Bliss (Don Ottavio), Paolo Bordogna (Leporello), Simone McIntosh (Zerlina), Joel Allison (Masetto), David Leigh (Il Commendatore)

Canadian Opera Company Chorus, Sandra Horst (chorus master), Canadian Opera Company Orchestra & Chorus, Johannes Debus (conductor)

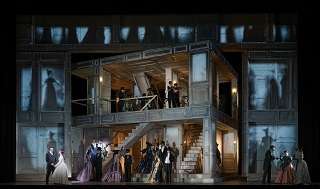

Kasper Holten (Stage Director), Amy Lane (Associate Director), Es Devlin (Sets), Anja Vang Kragh (Costumes), Bruno Poet (Lighting) Designer, John Paul Percox (Revival Lighting Designer), Signe Fabricius (Choreography)

(© Michael Cooper)

Don Giovanni, described by Wagner as “the opera of operas,” is a splendid work, thanks to Mozart’s sublime music and Lorenzo da Ponte’s brilliant libretto. Indeed, rare is the opera whose libretto is at least as good as its score. Da Ponte’s work can be appreciated on several levels, thus offering a plethora of possibilities to a talented and inspired stage director.

Intriguingly, the fables of Don Juan and Faust have inspired Western minds no end, over the past three centuries. Ever since Tirso de Molina’s El burlador de Sevilla y convidado de piedra appeared in 1665, no less than Molière, Goldoni, Lord Byron, E.T.A. Hoffmann, Pushkin, Tolstoy, Camus, Shaw, Kierkegaard and Michael Haneke have tackled the enduring theme of the dissolute serial seducer. In 1960, Ingmar Bergman wrote and directed Djävulens öga (“The Devil’s Eye”), brilliantly combining Faust and Don Juan.

Until the seventies, it was de rigueur that Don Giovanni was a wicked seducer, justly punished at the end. However, more recent productions have been more sympathetic to the protagonist. In part, this is thanks to a less puritanical outlook on the morality of love and sex. Another perspective is that of class. Don Giovanni, Donna Elvira, Donna Anna and Don Ottavio are aristocrats, while Leporello is a servant and Zerlina and Masetto are peasants. In the present production, Don Giovanni is shown as a maniacal pompous aristocrat, egotistical and delusional, but given the natural charm of baritone Gordon Bintner, he is also appealing. Despite his rank and charm, this “seducer” does not succeed in seducing his conquest du jour, Zerlina. Certain gimmicks used by director Kasper Holten insinuate that much of what we see is more in Don Giovanni’s mind than reality. This is somewhat true of narcissists; they see life from their very twisted perspective, thus justifying their whims.

Es Devlin’s elaborate two-storey palace is aesthetically pleasing and in some respects functional, but the separation of the characters on two levels diminishes the intensity of the interaction. The projection of the names of Don Giovanni’s conquests is a good idea, but repeating it ad nauseam made it somewhat tiresome. Also, one has to take dramatic liberties to fathom how Donna Anna’s home is in Don Giovanni’s palace unless she and her father, Il commendatore, were his guests for the night, or if the edifice was not Don Giovanni’s home, but an inn. This would explain why Donna Elvira, travelling from Burgos to Seville, would head straight there upon arrival to town. However, there is no indication of the latter possibility in the rest of the production.

Other than the projected names, ghostly apparitions of women clad in drab beige dresses, faces lightly‑veiled, roam around aimlessly throughout the opera. Apparently, these are the previously seduced women. Their traits are not visible as Don Giovanni can no longer remember them. This Gothic interpretation would be more appropriate had it been in Bartok’s Bluebeard’s Castle, as the women were murdered by the protagonist in that opera. But here, in the context of seduction, it’s jarringly moralistic and unnecessarily macabre. Mercifully, these bizarre roaming ghosts weren’t a great distraction.

In contrast, perhaps intentionally, Zerlina and Masetto’s wedding was made into a fancy event, replete with fantastic costumes. The two future spouses and their guests were sartorially as elegant as the four aristocrats (Giovanni, Elvira, Anna, Ottavio). However, elevating Zerlina and Masetto to rich peasants made them less apt to succumb to Leporello’s invitation, chez Don Giovanni, to enjoy “cioccolata, caffe, vini, prosciutti”; to advance the planned seduction. Zerlina would also be less likely the wide‑eyed naive ingénue, unable to resist Don Giovanni’s advances.

The present production was a missed opportunity, gathering an impressive cast, but this co‑production with London’s Covent Garden was of modest inspiration. The audience will only remember the projected names and the roaming ghosts, gimmicks not worth remarking on. There was also incoherence in the director’s view of Don Giovanni. The opening scene, in which he seduces Donna Anna, seemed more a tryst between consenting adults than rape by a disguised man. The idea is hardly new, but Kasper Holten doesn’t explore it. This is absurd, unless Donna Anna’s consent is a figment of Don Giovanni’s imagination, a confusing proposition.

Dramatically, Gordon Bintner dominated the performance with his immense stage presence and charm. His velvety bass‑baritone contrasted well with Paolo Bordogna’s more buffo bass‑baritone. The frenzy in his interpretation of the champagne aria, “Fin ch’han dal vino”, was almost alarming, appropriately indicating the nobleman’s hunger for life and insatiable appetite. His second Act aria “Deh! vieni alla finestra” was charm incarnate. This Don Giovanni had allure and sex appeal in abundance.

Though Paolo Bordogna is a veteran of comedic opera in Europe whose performances I have often enjoyed, his gags, dictated by director Holten, fell flat, and seemed forced. Many directors make the aristocrat and his servant mirrors of one another, especially as both usually have similar voices in the same lower register. However, no such attempt was made in this production. Indeed, they even lacked the chemistry one would expect of a nobleman and his valet of many years. Even a very busy Don Giovanni would need a few years to list over 2,000 conquests, as noted in Leporello’s catalogue aria.

Vocally, the most impressive interpreters were Armenian soprano Mané Goloyan as Donna Anna and Romanian soprano Anita Hartig as Donna Elvira. Goloyan has an impressive instrument and has no difficulty with the role’s high tessitura. Her “Or sai chi l’onore”, was commanding, despite some insecure notes. Her Act II aria, “Non mi dir”, was both technically brilliant and utterly moving. Antia Hartig’s high notes are still remarkable but the middle register isn’t as pretty as it once was. Nonetheless, she possesses a beautiful voice and is an amazing interpreter. Her Act II aria, “Mi tradì quell’alma ingrate”, almost brought me to tears.

Though endowed with a beautiful voice, Ben Bliss was miscast as Ottavio. His voice is not particularly Mozartian. Initially, he was able to harness it, making it lighter to fit the role, but eventually it was apparent that it was too heavy for Don Ottavio. More than the colour of his voice, Bliss’s style was non‑Mozartian. However, this had a dramatic effect, making his Ottavio more virile than one is used to. If this was a deliberate choice by the director, not much was made of it.

Vocally, Simone McIntosh was ideally cast as Zerlina. A natural soubrette with a beautiful voice and agility, she moved delicately onstage, perfectly impersonating “la giovin’ principiante”; the quality Don Giovanni finds most inspiring, according to Leporello’s “catalogue aria”. Nonetheless, she was not believable as a naive peasant girl, nor was she convincing as an ingénue. This may have been a deliberate choice by the director. If it was, subsequently it went nowhere. Unfortunately, there was little chemistry between her and Don Giovanni in the duet “Là ci darem la mano”.

Johannes Debus led the Canadian Opera Company’s orchestra with panache, clearly demonstrating his love for this cherished work. While the tempi may have seemed at times frantic, it was nonetheless appropriate, considering the inherent frenzy throughout this timeless drama.

Ossama el Naggar

|