|

Back

Whispers, breaths and trills New York

The Tenri Institute

05/29/2014 -

Perspectives and Tenri Institute Present “The Intimate World of Toshio Hosokawa”:

Toshio Hosokawa: Oshu Sashi for shakuhachi (Traditional Japanese) – Atem-Lied for solo flute – Two Japanese Folk Songs for soprano and guitar – Stunden-Blumen: Hommage à Olivier Messiaen, for clarinet, violin, cello and piano – Three Love Songs for soprano and saxophone – Lied for flute and piano – Vertical Time Study No. 2 for saxophone, piano and percussion

Miwako Handa (Soprano)

Ralph Samuelson (Shakuhachi), Perspectives Ensemble: Sato Moughalian (Flute and Artistic Director), Margaret Lancaster (Bass Flute), Pascal Archer (Clarinet), Cornelius Dufallo (Violin), Wendy Sutter (Cello), Oren Fader (Guitar), Eliot Gattegno (Saxophone), Stephen Gosling (Piano), Barry Centanni (Percussion)

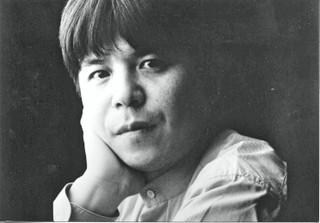

T.Hosokawa (© Schott Publishers)

A rare name in New York concert halls until this week, Toshio Hosokawa has been a most fashionable composer in Central Europe. A composer-in-residence with the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra, recipient of endless commissions, his operas and orchestral music premiered by the most luminous conductors, he is also honored in his native Japan–and this week was honored for the first program in New York Phil Biennial with his multi-layered The Raven.

I personally loved The Raven, a brilliant mélange of song, chant, orchestral textures and dance. Yet here, Mr. Hosokawa had a certain advantage. He was not working, as he usually does, with an assemblage of Japanese ceremonial music, mystic and Western avant-garde forms. He had, as the link or melody or story, the words of Edgar Allen Poe. And no matter how he dealt with it, Poe’s words were in the forefront of this mad eloquence.

Hearing an uninterrupted hour of Mr. Hosokawa the night after The Raven, even with the most splendid soloists from Japan and America, was less of a gift, more of a trial.

The audience was thrice admonished (twice in the program, once by a speaker) not to applaud between the seven pieces but to “enjoy the silences.” Had this been a program by Georg Friedrich Haas, the silence would be complemented by total darkness. But the Tenri Center, with its bright lights and whitewashed walls, was visually loud, and the entrances and exits of the performers left little to be silent about.

And while one expects a certain breadth in music, Mr. Hosokawa is far more interested in human breath. Margaret Lancaster didn’t play a solo bass flute, she breathed above the mouthpiece for a good half of the music. Elio Gattegno, a brilliant sax player, spent much of his own time breathing, and Pascal Archer started his clarinet solo in the Messiaen-inspired Stunden-Blumen with heavy breathing as well.

The breaths, as well as the incessant trilling from strings and winds, the off-key notes, the rumbles on the strings themselves, lent a kind of mystical emptiness to Mr. Hosokawa’s music. Perhaps it was meant to be lulling that we should appreciate the silences as well as the music, John Cage style, but at a certain point, enough was enough.

Yet the evening was worthwhile if only for the New York premiere from Miwako Handa, a soprano favored by the composer, and a woman whose extraordinary talent is still reverberating in my own ears.

Mr. Handa, I learn, not only is a opera diva (Susanna in Figaro, Nanetta in Falstaff), but a vocalist who has sung and recorded two Mahler symphonies with Eliaho Inbal, and who last night provided a memerizing miracle.

Billed as a soprano, it isn’t that Ms. Handa has a range going easily over three octaves, or that she was spot on at the lowest tenor or highest soprano part. That would make her an eccentric singer. But it was the coloring of her voice, the texture which could be lulling, or miraculously resonant, which possessed heartfelt drama or the gentlest tranquility.

Since she was singing Hosokawa’s arrangements of folk songs and haiku, she was at times limited to pentatonic singing. Yet such were the changes in her voice, her absolute verisimilitude and mastery of her voice, whether accompanied by off-key guitar (sensitively played by Oren Fader) or Mr. Gattegno’s breathy saxophone, that one would have wanted an entire recital.

Ms. Handa could be compared with the late Cathy Berberian, I suppose. But Ms. Berberian was as well known as a vocal acrobat as a great singer. Ms. Handa, perhaps employing as many tricks, could never have been called a showman. Her offerings of Mr. Hosokawa were performed with a longing, a truth, and a voice that defied description. (She, along with pianist Stephen Gosling, were the only artists who didn’t need those potent breath/trilling sounds to make their effect. Her voice was quite sufficient for any task.)

After the concert, I asked when she was coming next to New York. “Whenever,” she said, “it’s possible.”

Please, please make it soon.

The different segments of the concert each were worthwhile. Ralph Samuelson’s shakuhachi was as eloquent as another American virtuoso who plays at Tenri, James Nyoraku Schlefer. (Perhaps they are rivals, perhaps they toss raw fish at each other, but they both sound excellent to this neophyte listener.) Sue Moughalian is not only Artistic Director of Tenri, but here played a Lied for flute with another icon of advanced music in New York, Stephen Gosling. Like most of the music here, the work started with breaths, with whispers, and continued with a complex full-blown attractive music.

The final work, Vertical Time Study Number 2, used not only piano and saxophone, but–thank heaven–a nice controlled bit of banging percussion, with Barry Centanni. That “heavenly” thanks was due to the previous unending slow slow work which had preceded this last work. By Mr Hosokawa’s utterly sincere, metaphysical allegiances, those works had an authenticity from which one could not doubt. But listening to a set of loud staccato chords from these three, from listening to their mutual cueing, their actual surprising musical alliances, their various static scenes “walking through a Japanese garden”, one felt at least partly a Western motivation, a sense of velocity.

Just as Mr. Hosokawa had been “ruled” by the words of Edgar Allen Poe’s Raven, in his Vertical Time, he had challenged himself to present varying moments, not variations on silences. And after this, the admonishment for our own silences was finished. For the artists alone, this listener finally had the joy of hearing the sounds of two hands clapping.

Harry Rolnick

|