|

Back

The Bards Are Singing New York

Zankel Hall, Carnegie Hall

04/22/2014 -

collected stories: hero

Benjamin Bagby: Scenes from “Beowulf”: I. “The Monster”; II. “The Hero”; III. “The Fight”

Harry Partch: The Wayward: a. “Barstow”; b.”San Francisco”; c. “The Letter”; d. “U.S. Highball”

Benjamin Bagby (Storyteller and Medieval Harp)

Harry Partch Institute Ensemble of Montclair State University, New Jersey: Stephen Kalm (Baritone), Robert Osborne (Bass-Baritone), Charles Corey: (Kithara II and Cloud-Chamber Bowls; Producer and Musical Director), Christi L. Corey (Surrogate Kithara), Sverre Kyvik Bauge (Cello and Harmonic Canons), David Broome (Chromelodeon I), Joe Fee (Diamond Marimba and Spoils of War), Joe Bergen (Bamboo Marimba, Bloboy and Cloud-Chamber Bowls), Matt Olsson (Bass Marimba)

Jon Roy (Artistic Director, Video Artist and Projection Supervisor), Philip Blackburn, Alice Peragine (Video Artists), David Lang (Curator “collected stories”)

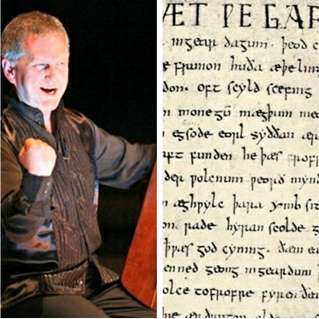

B. Bagby, Beowulf Ms (© Hilary Scott/Public Domain)

“’collected stories’ divides the world not by genre or style, but by various kinds of stories that a piece of music can tell in order to see how the story and the composer work together.” David Lang, Holder of 2014-2014 Richard and Barbara Debs Composer’s Chair at Carnegie Hall and Curator of collected stories

To those raised in the Stravinsky dicta that music is music, unable to project anything more than its notes, composer David Lang has taken on a heady task. Namely, that these six days in Carnegie Hall should present music as story, music relating heroes, lovers, wanderers, mystics.

Nor do the adjacent stories give easy access. Performers each night jolt against each other. Ancient Siberian chants next to modern mystical chants. John Cage against...well, a new work by David Lang himself.

Last night, the stories were paired a millennia apart, encompassing as many contradictions as eloquences. Did the medieval story-teller Benjamin Bagby really sing a truncated Beowulf the way it was sung by bards in the 11th Century? Or was Beowulf actually ever a bardic work at all? May it have been unsung but only notated? Was the multi-talented Mr. Bagby the owner of a real medieval harp actually tuned the way it could have been in that same century?

As for the second work, an opera by Harry Partch, produced by equally gifted ensemble from Montclair State University, they may played Mr. Partch’s original instruments, but the composer might have been either gratified or appalled by the multi-visual background for his folkish resonating tales of the peripatetic life.

Those thoughts, especially of Mr. Bagby, are after-thoughts. For even in ancient Anglo-Saxon, which resembles Martian equivalent of Welsh, Mr. Bagby was absolutely mesmerizing. His stage voice is a highly dramatic baritone easily managing to get in the bass range. But this is like saying that Sir Lawrence Olivier was restricted to a particular compass. For Mr. Bagby is above all dramatic, in the best Shakespearean way.

The translations–telling how the monster Grendel destroyed the Heroes of an ancient Danish tribe, before being defeated by the visiting knight Beowulf–were flashed on the wall of Zankel auditorium, but Mr. Bagby almost didn’t need them. His voice quivered with rage that a monster would eat Christian knights. His voice drunkenly related another knight belittling Beowulf, and his voice compassionately soothed that inebriated nay-sayer.

Somehow, his “medieval harp”, the six strings apparently tuned in a modified pentatonic scale, could be rippled with glory, the strings struck with angry bangs, or essentially accompanying the Bard on his tale of utter heroism.

How authentic was this? We shall never know. But on a personal note, I was wandering in rural Albania a few years ago, when two wandering troubadours showed up in my rustic guest house to recite, with a much larger lute, some medieval battle of Albanian history. Their voices also quivered and raged and gave redolent literal pictures of this chants and songs. And like Mr. Bagby’s Anglo-Saxon, I believe these Albanian bards had been speaking their own archaic form of Albanian, possibly closer to the original Illyrian language of the area.

Mr. Bagby, whether or not authentically replicating the medieval story-telling of the Eleventh Century (he calls himself “a reconstructed singer of tales”) was a dramatic master at the sarcasm, bonhomie, horror and of course heroism of another age. This was indeed an abbreviated version of Beowulf. I look forward to an entire evening of what we blasé readers might call the audio version of that great epic.

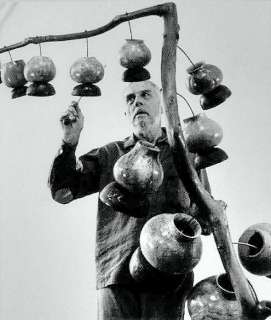

H. Partch and gourd-tree (© Commons@wikipedia.org)

The second work, a four-story “opera” by Harry Partch, was the first vocal work I had ever heard from the iconoclastic inventor/hobo/composer. To me, the music of Harry Partch will always be a magical instrumental phenomenon. The names of the instruments (shown above in the list of performers) are interesting enough. But the sounds of his Bloboys, diamond marimba and cloud chamber-bowl are the equivalent of Benjamin Bagby’s Anglo-Saxon.

Specifically, they sound nothing like our modern sounds. Harry Partch rejected Bach’s well-tempered scales and brought influences which encompassed another world of music. His influences bear repeating:

“Yaqui Indians, Chinese lullabies, Hebrew chants for the dead, Christian hymns, Congo puberty rites, Chinese music halls (San Francisco), lumber yards and junk shops...Boris Godunov...”

The sounds are resonant, tingling, echoing, plangent, always off-key. Most “inventive” composers of the last century confined themselves to percussive innovations and different fingerings. Mr. Partch created his own world.

Those instruments were played with fantastic agility by the students of the Harry Partch Institute. Added to this, for three of the four segments, were videos which included old footage (of 1910 San Francisco, barren deserts) and live intercepts of the players.

The video of the final “US Highball” was a technical mess, as if the producers hadn’t had enough time. That was a distinct shortcoming.

Onto the stage with its instruments danced two singers who romped and jumped and sang and moved as if they came out of an Aaron Copland ballet. Their hijinks were amusing–to a certain point. Then, like the videos of the final section, they became wearying.

In other words, the stories and music and dancing and singing became a spider-web of forces which negated themselves. After the concert, I put on a YouTube audio section from “Wandering” to be more gratified than these so talented performers in a multi-visual world.

It was still an enlightening evening. Tonight I go to hear David Lang’s “collected spiritual stories”. Preparation is irrelevant. My mind is open, for the narratives encompass the sheerly unpredictable.

Harry Rolnick

|