|

Back

Rare Partnership, Rare Music New York

Avery Fisher Hall, Lincoln Center

04/02/2014 - & April 3, 4, 5, 2014

Benjamin Britten: Four Sea Interludes from Peter Grimes, Opus 33a

Béla Bartók: Piano Concerto No. 3, sz. 119

Dmitri Shostakovich: Symphony No. 10, Opus 93

Peter Serkin (Pianist)

New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Pablo Heras-Casado (Conductor)

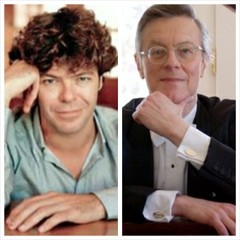

P. Heras-Casado, P. Serkin (©Courtesy of the Artist/Regina Touhey Serkin)

Perhaps there are stranger partnerships than Peter Serkin and Pablo Heras-Casado, but we will have to be satisfied with this singular duo.

Three years ago, the reserved New York pianist, scion of a musical aristocracy, and the dynamic Granada-born conductor who has whizzed to glory, winner of a Musical America “Conductor of the year” award, came together like old friends, playing a program of rare Stravinsky with the International Contemporary Ensemble. Last night, the two joined forces again, this time for the Bartók Third Concerto.

And if the Serkin/Heras-Casado duo will never have the popularity of, say, Hepburn-and-Tracy or Bogart-and-Bacall, they certainly stand out in the Manhattan musical spotlight.

The occasion last night was Pablo Heras-Casado’s debut with the New York Philharmonic, which is far overdue. The Spanish conductor leads a neighboring orchestra already (St. Luke’s) and has conducted virtually every other international orchestra, so this opening performance was already foreseen as one of the highlights of the Spring season.

His choices were limited but wise. A master of contemporary music, and more than adequate with the mainstream repertoire, Mr. Heras-Casado chose three works which were genealogically “modern” (i.e. written 60-odd years ago), they were not 20th Century abstruse (more rhythmic than algo-rhythmic dodocephonia), and all had the emotional grips on audience which the conductor can produce.

The Serkin was not only the centerpiece, but the Bartók was indeed an elegiac performance. It was neither sharp nor acerbic, for this was one of the composer’s final works, a meditation more than a maelstrom.

Perhaps Messrs Serkin and Heras-Casado started too hesitantly, but in this conception, there was nothing to urge them on. If the tempo was a bit slow, and the next Adagio religioso played even slower than usual, both artists were prepared to take their time, to allow Bartók’s tranquil, even Baroque thoughts to come out.

(The program unfortunately wrote that this second movement was an “Allegro religioso”, but the error does send the imagination into wondering how that would sound.

Both musicians allowed the Presto to be fast enough, but there was enough relative restraint for the contrapuntal fireworks, and an unfettered blazing end to their Wednesday partnership.

Mr. Heras-Casado started the program with a totally different music, written in the same year, Benjamin Britten’s ”Peter Grimes” Interludes. The conductor never needed a baton for the evening, but his movements were exquisite enough, the solo playing by the Phil and some lovely string playing evoked some of the most evocative music of the evening.

(I had no idea this was for an opera when I first heard these four sections as a child, but still recall my mind somehow going back a few centuries, still somehow thought of those momentary string calls as light glints on the sea. Britten didn’t always reach that image, but he certainly succeeded here.)

Weirdly, many in the audience disappeared after the intermission. They missed something quite stunning. For little was held back for most of Shostakovich’s Tenth Symphony, though Mr. Heras-Casado had two arduous challenges. First, how to hold that long long introduction to the finale. He didn’t quite manage it. The music itself is inspired, but rare is the conductor who can grip onto those measures. Those who knew the symphony last night were probably saying, “Get on with it, Maestro. Enough broccoli. Let’s feast on Shosty’s birthday cake.”

Far more successful was the even longer line of the first movement, an arch whose momentum and buildup were not only subtle but agonizing. His restraint of the orchestra, the cellos supporting the double basses, the flute and clarinet solos all were parts of a majestic structure.

It goes without saying that the two scherzi (the second movement and the last half of the finale) are joys for any young conductor of Mr. Heras-Casado’s genius, so he allowed the NY Phil to play with power, solo legerdemain, and a dash (though never a mad dash) to the finish line.

Harry Rolnick

|