|

Back

"Waiter, There’s a Feather in my Bagel!" New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

03/14/2014 -

Franz Schubert: Symphony No. 8 in B Minor (“The Unfinished”), D. 759

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 4 in G Major

Juliane Banse (Soprano)

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Christoph Eschenbach (Conductor)

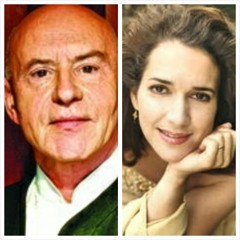

C. Eschenbach, J. Banse(© Eric Brissaud/Suzi Kroll

An old New Yorker cartoon once showed a conductor lifting his baton for Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, then turning to the audience and with a smile, saying, “Okay, stop me if you’ve heard this one.”

Some music, in fact, is so great yet so familiar, that any listener must take a deep breath and say to him/herself, “Okay, let’s pretend listening to this for the first time, as if we’ve never heard it before. Yes, the Beethoven, of course Carmen, and last night, the challenge was hearing Schubert’s Eighth Symphony as if we had never discovered it as a child, as a teenager, as a student conductor, and as a concert favorite.

With Christoph Eschenbach on the podium, and with the Vienna Philharmonic–who would have given the premiere if Schubert had finished it or the 174-year-old orchestra had been invented–that was not a difficult feat. Mr. Eschenbach must have conducted it thousands of times, but as a man of utmost integrity, he would have heard the music in his mind (naturally he needed no score) and given it a reading as if it had just been written.

True enough, this was a very special reading. In fact, it was a chilling performance.

One expects that opening to be ominous, but, like Haydn, good old Franz would have burst into something melodiously shining. Nothing glittered here. Mr. Eschenbach’s orchestra burst out with fearful tremolos, the oboe theme had a nuanced half-hearted melody, and when the orchestra played as an ensemble, the reading was tragic, harsh, the kettledrums banging out funereal tattoos rather than metrical backgrounds.

While the truth may be that the composer “forgot” to finish it, Mr. Eschenbach showed that Schubert felt that he couldn’t finish it. How (he might have asked) do you write a scherzo after writing the equivalent of Dante’s Inferno?

In fact, so bitterly immoderate was the music for a titular Allegro moderato that the second movement’s tranquility came as an afterthought. Had Schubert heard Mr. Eschenbach play the opening, he might not even have continued it after that, and simply left it as a tragic overture.

The following Mahler Fourth is almost as popular, but one never needs to fear this music. Like three of his first four symphonies, it is vernal, uplifting, a paean to nature and life. This one, though, is almost naive, almost pure. No tubas, no trombones (the virtuosic horn parts, played by Ronald Janezic, replaced them and were played faultlessly), the sounds of sleigh bells and final words like a vegan’s gourmet menu. (One tries to imagine the butchered lamb was symbolic.)

Mr. Eschenbach never tried to find an underlying tragedy here. Except for some exaggerated pauses, it was pointed, genial, had some terrific First Chair playing, and the soloist was...well, we’ll come to that later.

The first movement was taken exactly as Mahler has it in the score. “Deliberate”, but also “Nicht eilen”: Don’t screw around, but play it as “face value.” For the scherzo, Rainer Küchl changed violins for the scordatura pitch-raised demon song. Yet there was nothing demonic here. Like the first movement, it was placed placidly, with a bit of piquancy, a scintilla of wit.

In the slow movement, the Maestro broke the rules–and came up with one of the most visually arresting moments I had ever heard in this symphony. The Vienna strings were perfectly clear, the pace was moderate, the sounds were lulling.

And then came the climax for which everybody waits. The orchestra is playing pianissimo in G, as if nothing would interrupt the lullaby. There is a hush, a muting, and sforzando, and the whole orchestra bursts into a forte fortissimo section of trilling and arpeggios and glissandi, not like a Big Bang, but an angelic raising of the universe curtains.

Simultaneously, with these wonderful sounds, the soprano of the evening, Juliane Banse, walked to the center of the stage.

The first reaction was revulsion: why should she interrupt the proceedings. Within a fraction of the second, it was obvious that Ms. Banse was the embodiment of the Annunciation, that her presence and forthcoming song would be the personification of these heavenly sounds.

It was not only dazzling and iconoclastic, but it worked. For Ms. Banse, while operatic enough, eschewed emotion for the luscious gifts of heaven. Oh, how I wish that they were sung in English for this audience. To hear the words of “singing and leaping, sipping and dancing...free wine... herbs and asparagus, pears and grapes... bread baked by angels.” (“Waiter, there’s a winged feather in my bagel!”)

The words are angelic. Ms. Banse’s softness as she spoke of St. Peter looking on, her effortless creamy high notes, didn’t create the illusion of a child’s heaven, it was a child’s heaven.

No amen for this religion, but an ode to “joyful awakening.” Mr. Eschenbach retained that vision. For after the last pianissimo low E on harp and double basses, the conductor did not lower his hands but kept them aloft for 45 seconds.

It was a celestial hush.

Harry Rolnick

|