|

Back

Ecstacy, Exaltation and Escher New York

SubCulture, 45 Bleeker Street

01/12/2014 -

Marc Neikrug: Passions, Reflected for Solo Piano (World premiere)

Poul Ruders: String Quartet No. 4 (U.S. premiere) (#)

Marc-André Dalbavie: Trio No. 1 for violin, cello and piano

Yefim Bronfman (Piano), Musicians from the New York Philharmonic: QuanGe (#), Fiona Simon, Sharon Yamada (Violins), Robert Rinehart (Viola), Eileen Moon, Maria Kitsopoulos (#) (Cellos)

Marc Neikrug (Host)

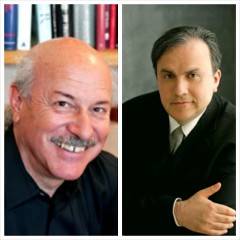

M. Neikrug, Y. Bronfman

(© Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival/Dario Acosta)

Budding writers are scolded when using too many exclamation marks. “Contact!” should be denounced for restricting itself to one.

Created by Alan Gilbert as an adjunct to New York Philharmonic programs, it has attracted not only the best composers, commentators and musicians, but audiences who yearn for music of our time. Without frills, apologies or (what would be true for the usual Phil audiences), yawns and rustling of programs.

True, Pierre Boulez tried to inculcate NY Phil audiences into contemporary music, but they apparently resented this interruption to the familiar. Bernstein condescended as much as he charmed. But Mr. Gilbert–lauded by composers like Marc Neikrug last night for his performances–knew that he had to change the setting, to make it an occasion akin, perhaps, to those 1920’s salons attended by Stravinsky, Ravel, Bartók et al.

The Met Museum provided an excellent space, but SubCulture Underground has more of a communal feeling. This, after all, is the Village, not “uptown”. So the audience last night for “Contact!” gathered, beside Mr. Gilbert, a plethora of NY musical illuminati for three works played by equal illuminati on stage, including Yefim Bronfman and NY Phil soloists.

The host was one of our finest composers himself, Marc Neikrug. His descriptions, eschewing the technical, used words of emotion (“Ferocious!”, “Fresh!”) to describe the music of three composers, including himself. In fact, the opening work was his Passions, Reflected for Piano Solo, proof enough that Mr. Neikrug can easily wear his heart on his musical staff.

His music sometimes has purposes outside of the notes (he has researched and written for music in healing), but in the world premiere of Passions, he gave Yefim Bronfman twelve pieces to play. In the resemblance to Schumann, the works are different but should not be differentiated. Thus, each piece here was given an apt description.

That was an irony, for the pieces are titled I, II, III...XII.

Still, like the Schumann piano works he adores, the twelve pieces are part of a whole. And the passions did take many forms. With number I, Mr. Bronfman stayed down in the bass with a repeated impulsive cell of three adjacent notes. I heard these same notes throughout the rest of the piece, but that could have been my imagination trying to justify the structure.

Those dozen works were never afraid to go for the most dissonant harmonies. But they were never really harsh. Instead we did have twelve moods. They ranged from the highly emotional to (in number VI) the sentimental. Then again, isn’t sentiment one of our moods? Why always aim for Olympus when we’re living on earth?

Number VII or VIII (my notes are scrawled) was a grand waltz, and possibly Mr. Neikrug was attempting a double homage. Deference to Schumann who in his own waltz gave deference to Chopin. Other pieces took more ambivalent gestures as Mr. Bronfman plunged up and down the keyboard until the ultimate (and longest) of the “movements”.

Nicely, these were not Webernian bagatelles, where each note had to make sense. In fact, they were more like some of Prokofiev’s image-works for piano. But Mr. Neikrug gave feeling to the piano, with his own passions, both micro– and macro-cosmic.

In the middle of the evening was Poul Ruders’ Fourth String Quartet, and like all else by this Danish giant, the intensity, the ferocity (Mr. Neikrug’s word) and unfettered macrocosmic state was offered in five totally engaging movements.

Mr. Ruders never ever lets an instrumental color be left behind. This might have been a string quartet (and the four players listed above gave it pulse and impulse), but he created the most delicious sounds. The first movement included resonances on each instrument, so the strings were held, or bounced off each other, and one felt as in a Baroque cathedral, not an East Village bar. The second was purely Beethovenian, a scherzo and trio, the latter of which formed part of the final three movements.

This was Poul Ruders the magician, taking that simple ländler-like theme and pushing it into a variety of ferociously fast movements, tours de force into complex equations, everything from a Beethoven-style quick run up to the theme to again an aural discovery, where the instruments could have been four bells or gongs.

No special effects were used here. Simply harmonics, high tones bouncing off high tones, resonances leading to resonances. And a finale that was like a rest period for the frenzied music which had gone before.

Now it was back to Mr. Bronfman, the Phil’s artist-in-residence. No adjectives can capture his persona. “Indefatigable ” or “endlessly curious” or “vital” or “titanic” scratch the massive surface of this great Tashkent-born artist. So, not content with playing Mr. Neikrug’s twelve pieces, he came out with two Phil artists–violinist Quan Ge and cellist Maria Kitsopoulos–for a piece which could be described as “Escher in music.”

Marc-André Dalbavie was once dismissed by Pierre Boulez as “easy to grasp.” If that was an insult by the Gordian-knotty Boulez, it was wrong. Mr. Dalbavie may be less convoluted than Boulez but the complexities of this First Trio were endlessly fascinating.

It began with a dozen gun-shots. Rather, Mr. Bronfman banging those gunshots hotly and fiercely on the piano, followed timidly by strings. But now came the Escher conundrum. Each instrument was flexibly restricted to play scales. Endless scales up and down, mixing modes, interrupting each other, producing Escher’s illusion of an architecture rising and falling, each instrument transformed into more and more complex equations, sometimes out of tune, sometimes together, until the whole dizzying 18-minute riddle within riddle within riddle was suddenly stopped!

Stopped by the same gunshot notes in which Mr. Bronfman opened the piece.

Mr. Neikrug himself said, “I’m not sure how he does it.” And if that composer is baffled, who are we poor mortals to figure it out? Except that it was delightful intriguing, and, like the hour-long concert, infinitely joyful.

Harry Rolnick

|