|

Back

The Levine-Mahler Love Affair New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

12/22/2013 -

Gustav Mahler: Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen – Symphony No. 7

Peter Mattei (Baritone)

The MET Orchestra, James Levine (Music Director and Conductor)

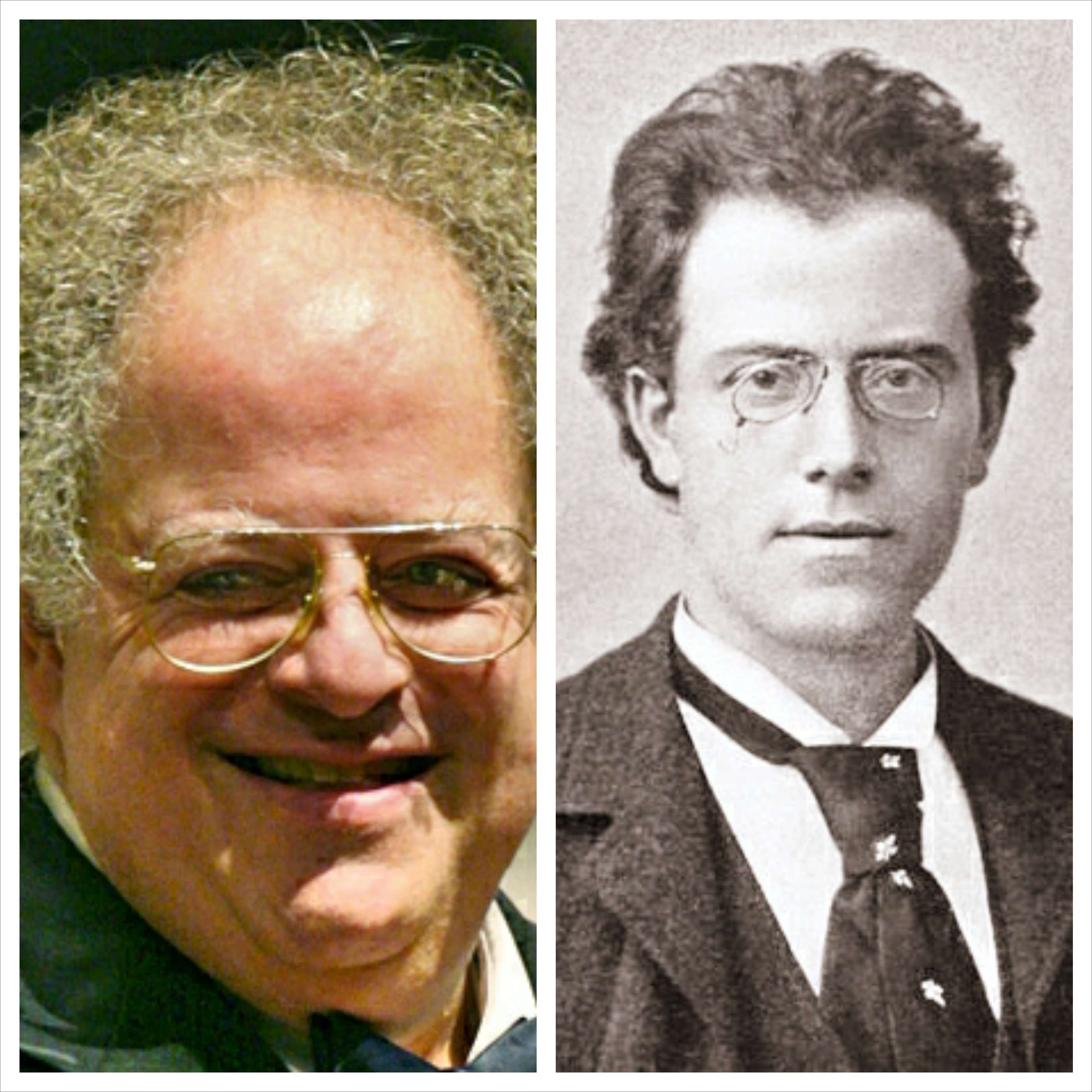

J. Levine/G. Mahler (© Michael Dwyer/AP/Wikipedia Commons)

For over 2,000 years, sages and patriarchs have debated whether Mahler’s Seventh Symphony is appropriate the weekend before Christmas. The answer is hardly Talmudic. Gustav Mahler is a composer for all seasons. And like Mozart, he was never afraid to pile emotions on feelings, trivial tunes with heavenly harmonies, godawful parade marches with gargantuan structures.

As for the Seventh, the challenges may be greater than all the rest, since its contradictions, elegies and drum-banging street marches, are almost impossible to make cohesive. Except...except that in Mahler’s case, Classical or even Romantic cohesion isn’t the goal. Whatever explanation he might have given was obviously a momentary whim.

The music of the Seventh, though, is such an enigma that any listener–or any conductor–who tried to understand it with words would miss the utter pointlessness of the thing. If it did have a point, well, the art would disappear.

My words are mundane, because James Levine, exciting, vibrant, alive, if not quite ambulatory (he used his very mobile wheelchair) did give a pointed performance yesterday with the MET Orchestra, an ensemble he had transformed into one of the world’s great orchestras. And the Seventh yesterday was anything but describable. Under Mr. Levine, this was Medieval tapestry of infinite designs, obsessive rhythms, and–at the end–a gorgeous reprise including those previous fragments, and some Wagner thrown in as well.

In fact, Mr. Levine turned the Seventh into almost a paean of joy. Yes, we did have that famous lachrymose tenor horn solo, but Mahler’s description, “Here nature roars” was for a non-dangerous roaring for a march which could have come from Charles Ives. The repetitive tattoo, under Levine’s hands was hardly a psychological quirk as much as a structural device for bringing in a whole collage of sounds, tunes, ravishing climaxes and tinhorn repetitions.

While the work is hardly ever played in New York concert halls, recordings give it a thick orchestration. Here, though, James Levine gave us the al fresco version, almost a Mozart divertimento that, should one miss a few bars, would still stand with loveliness on its own. Okay, that bass trombone growls out before the end, but this is not so much nature roaring as an announcement that nature is alive and well.

Mahler then seems to say, “Well, if you don’t like that march, I’m gonna give you yet another march. Take it or leave it.” Fortunately, the horn calls and echoes offstage hit just the right bucolic notes.

The third movement missed something. It missed the wicked satire of a waltz. In fact, this was a real waltz, without any ghostly Fantastique apparitions. Written literally midway between Rosenkavalier and Ravel’s Valse, it was an unstylized appreciation.

One gets the idea that Mahler is sometimes showing off here. His mandolin and guitar and harp in the fourth movement, the soft sounds, the shadowy mime show was the expert designer not afraid to hyperbolize his genius.

And this was proven by the almost riotous finale. That’s when one begins to suspect that this was the equivalent of Beethoven’s Sixth after the Fifth. Mahler followed the sometimes lugubrious Sixth with this celebration of music.

Yes, celebration, not cerebration. With Mr. Levine on podium, with the MET Orchestra brass at their brassiest, one should have felt guilty if the music was “washing over” the listener. But one had no reason to. Mr. Levine played us music which was so beautiful, quirky and even relaxed that we heard the most unexpected Mahler possible, and his standing ovations were worthy of the Levine name.

P. Mattei (© Allmusic.com)

The enigma of this symphony stood out even more with the opening Songs of a Wayfarer, written almost two decades previously. Had Franz Schubert lived another 50 years, he would have written the same melodies. Unlike the Seventh, they were never ambiguous, they were direct, with poetry and melody complementing each other, and Swedish baritone Peter Mattei giving it a rousing performance.

Mr.Mattei is an opera singer, and he soared best in the highly dramatic “I have a glowing knife...Ah, woe! Ah, woe!” That third song gave him the chance to exercise a thrilling fortissimo. Not that the other three songs were bad. It was always a comfortable Mahler, a delightful Mahler. What James Levine attempted was to take the musical labyrinths of the Seventh and show that Mahler never departed from that selfsame happy tossing of his spirits to the world, for savoring and remembering.

Harry Rolnick

|