|

Back

Holy, Holy, Holy New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

03/10/2013 -

Osvaldo Golijov: La Pasión según San Marcos

Jessica Rivera (Soprano), Luciana Souza (Vocalist), Reynaldo González-Fernández (Afro-Cuban Singer and Dancer), Deraldo Ferreira (Capoeirista and Berimbau)

Members of Schola Cantorum de Venezuela, Maria Guinand (Chorus Director), David Rosenmeyer, Music Supervisor, Forest Hills High School, Frank Sinatra School of the Arts Concert Choir, Heidi Best (Chorus Director), Songs of Solomon, Chantel Wright (Chorus Director), Orquesta La Pasión, Mikael Ringquist, Gonzalo Grau (Leaders), Robert Spano (Conductor)

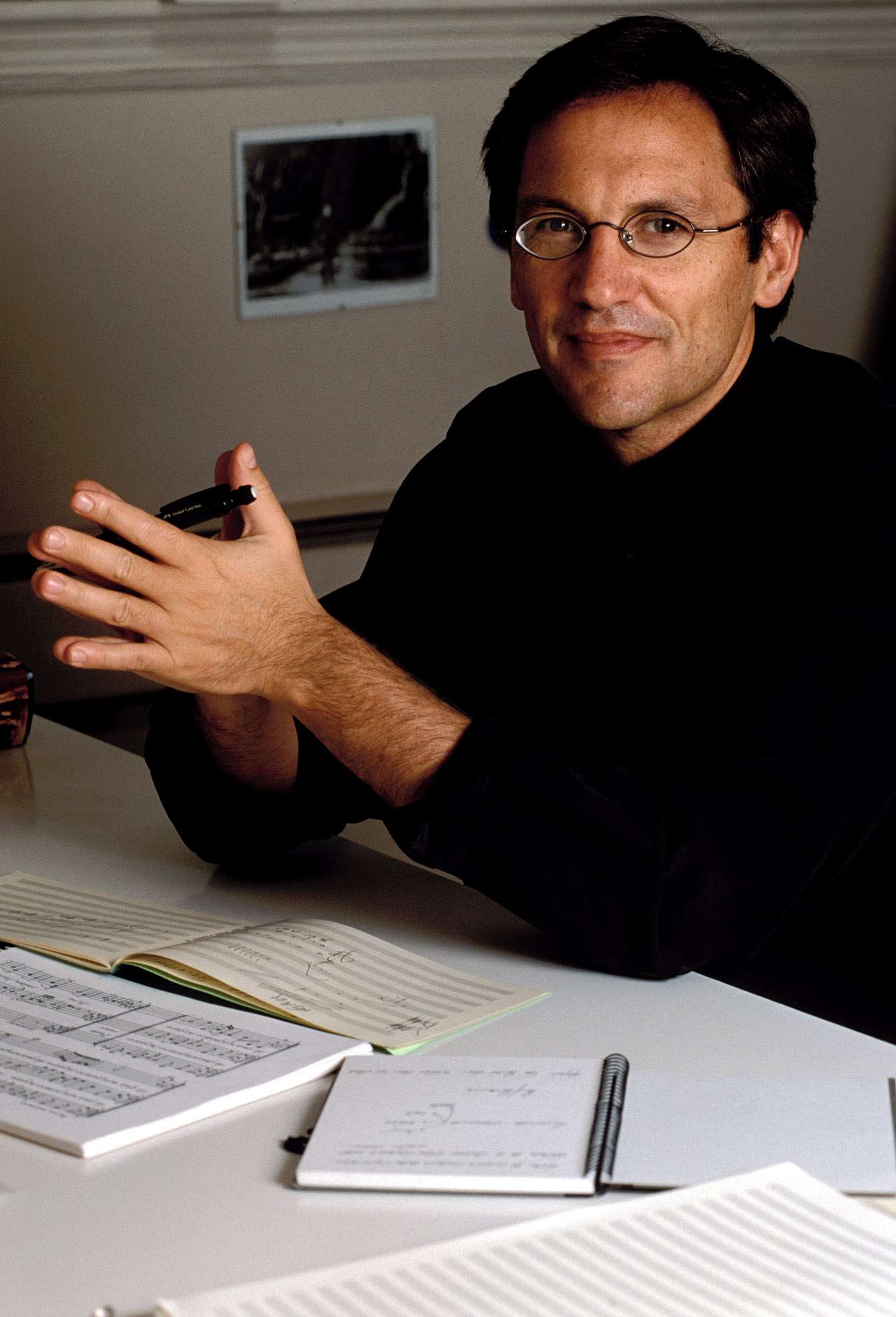

R. Spano (© Angela Morriss)

After 90 uninterrupted minutes of percussion, chorales, sambas, chants, alto beatitudes, soprano arias, and credos involving African, Brazilian, Hebraic and Christian passions, the full house Carnegie Hall audience rose en masse in their own Hosanna for Osvaldo Golijov’s La Pasión según San Marcos yesterday afternoon.

More self-judicious listeners might have raised the inevitable eyebrow, looking at the joy of the plebs. In this case, though, the Carnegie Hall premiere of the decade-old spectacle was an unalloyed triumph. The comparisons were obvious–Bernstein’s Mass, Penderecki’s Passion, John Adams’ El Nino, all amongst the worthiest. But Mr. Golijov provided one extra factor to the music and that made all the difference.

That ingredient was movement. Total movement. The chorus–an amalgamation of Venezuelan and American singers, dressed in purple and white, the colors of the highest Yogic power–moved back and forth, swayed, faced each other, bowed, turned the Gospel of Saint Mark into a Mystery Play of gesture and feeling. The soloists entered and exited from the stage door, emphasizing the drama. Drummers in front of conductor Robert Spano moved with their congas and maracas, with their thundering timpani, and soft bells.

J. Rivera (© www.jessica rivera.com)

Afro-Cuban dancer Reynaldo González-Fernández did the impossible. He moved with the most daring acrobatic tricks, but they seemed to be done in slow motion, not the usual gymnastics but the grace of an Astaire. Mr. Fernandez and Luciana Souza, a fervent alto, sung with earthy passion, while soprano Jessica Rivera, with and without the chorus, gave elated movement to her solos, especially the operatic aria, “Colorless Moon”.

Above all, the movements were percussive: ringing, thundering, with an incessant, almost eternal feeling of swaying and dancing, kinetic throbbing.

This was on the surface. The crux of Mr. Golijov’s Passion was the composer himself. Growing up Jewish in Catholic Argentina, he admitted never having opened up a New Testament in his life until the commission of this work in 2000. But with his background, his incredible talent, and his eclectic appreciation of all the worlds which had opened to him, he could use the background of Brazilian music and religion (more on that below), his feeling of the Passion of Christ, his study of Aramaic languages (the original language of Jesus) and Hebrew and the mystic, irrational feeling of the Resurrection.

What happened now was almost miraculous. Everything fit together: the Kaddish (the same Hebrew prayer which Bernstein loved and set), the story of Jesus as a child and as the sacrificial lamb, and the magic of Brazil itself.

In particular, Golijov had mentioned the African background of the Brazilian state of Bahia. I have never been there, but reading Umberto Eco’s novel Foucault’s Pendulum, with is hundred-odd pages devoted to the rituals of Bahia State, and its relationships to all the mystical rituals of the Middle Ages, I began to understand what La Pasión según San Marcos was all about. (Though, granted, Mr. Eco, the world’s foremost semioticist, could probably unite the history of the Catholic conclaves this week with the history of Girl Scout cookies.)

Mr. Golijov, thus, here could see the “catholicism” of the Catholic Church. He could bring in a live Christ coming down the aisle of Carnegie Hall, being beaten on stage, he could bring in a long song called “Agony” which sounded part Bach, part Brazilian, to reach inside the suffering of Jesus. He could work solo movements only of percussion, and this deepened the feeling of elation.

It was not audacity, but a religious motivation where Jesus, Peter, Pilate and others were played by different segments: chorus, soloists, even musicians. It was equally necessary that the choruses came from South America (Venezuela) and schools in New York and New Jersey. Here was the universality of the Passion, the feeling of the Saddhu and the Brazilian street-hawker, the drummer and the artist, that the spirit does not dwell in the church, on the Cross–or even in the concert hall. But that it exists within us all.

O. Golijov (© Sara Evans)

The forces here were as massive as the inspiration by the composer, who was present and came out to tumultuous applause. Then again, it is virtually impossible to assemble such forces for an ordinary performance, and Mr. Spano has become, so far as I know, the only conductor of the work.

And that inspiration was present from the first beautiful two-minute introduction to the final “Amen.” Mr. Golijov’s work has at times been disappointing. (His setting of Neruda poems, heard a few weeks ago, did little benefit to the poet.) But with a work like this, he transcended himself, and almost transcended his subject.

Since I was as overwhelmed as the rest of the audience, it would behoove nobody to give more hosannas, more praise to this splendid epic work. Instead, I must end with the retelling of an old Jewish joke.

“Tell me, Rabbi, is it true that true artists will dwell in heaven?”

“I cannot give the answer to this question. But I can say that heaven dwells within the true artist.”

Part of that we heard Sunday afternoon. And for that privilege, again, “Amen.”

CODA: Writing that Robert Spano was probably the only conductor of La Pasión según San Marcos, I hadn’t realized that the work, dedicated to the Schola Cantorum de Venezuela, has been performed by that group more than 50 times, in Venezuela, America, Europe and Australia. Most of those times, it has been conducted by María Guinand, leader of Schola Cantorum. On a personal note, it would be wonderful to see María Guinand in New York to hear another interpretation of this marvelous piece. By the way, should the first Jesuit Pope from Argentina need a Sistine Chapel Court Composer, he could do worse that select Mr. Golijov as the first Jewish musical director from Argentina.

Harry Rolnick

|