|

Back

Rachmaninoff, Celebrated Houston

Jones Hall

01/05/2012 - and January 7, 8, 2011

Richard Wagner: Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg: Prelude

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto No. 3 in D Minor, Op. 30 – Symphonic Dances, Op. 45

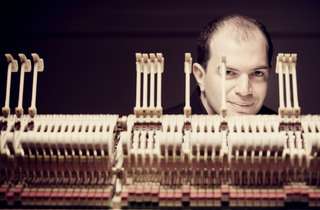

Kirill Gerstein (piano)

Houston Symphony, Edward Gardner (conductor)

K. Gerstein (© Marco Borggreve)

Despite any arguments to the contrary, it is odd to begin a festival celebrating the music of Rachmaninoff with a work by Wagner. Guest conductor Edward Gardner offered an awkward apologia before diving into the Meistersinger prelude, citing the influence of Tristan und Isolde on The Isle of the Dead. Perhaps this is true at a superficial level, but neither of those works was present here. Indeed, the major qualm I'd have with the Houston Symphony's tripartite RachFest is the lack of imagination in its conception. Sticking solely to the composer's "hits," no matter how well performed, simply doesn't provide any interesting illumination into the composer's work. We've heard the second and third piano concertos in the past two years, as well as the second symphony. Why not replace the Wagner with Rachmaninoff's delightful early Scherzo in D Minor? Why not involve the fantastic Houston Symphony Chorus and put on The Bells? Fortunately, the warhorses presented are damn good music, and the first concert in the series laid a solid foundation for its subsequent episodes.

It seemed as if Gardner was attempting to "Rachmaninoff-ize" Die Meistersinger in his interpretation to make it fit in. The opening was a tad soggy and overly legato, lacking a grandeur in articulation and propulsion. Things picked up in the central episode, with the orchestra's wind soloists delightfully pecking along in Wagner's contrapuntal web, and the brass section finally arrived with exciting impact at the climax.

Kirill Gerstein is on hand for all three concerts in the series, taking on the Herculean task of performing Rachmaninoff's four concertos in a matter of weeks. It is perhaps smart that he began with the third, arguably the highest summit to conquer, and his performance was thrilling. His previous engagement in Houston, performing sparkling renditions of Ravel's G major concerto and Rhapsody in Blue, revealed a transparent, French-influenced playing style married to prodigious virtuosity and intoxicating élan. Tonight, he switched gears, again mustering every facade of his pianistic dexterity, but achieving a darker, bolder tone throughout. His phrasing of the famous opening tune was po-faced almost to a fault. One almost sensed disinterest, but this was immediately cast aside when Gerstein launched into his first flourishes with aplomb.

There were many highlights from the keyboard, including a crushing reading of the original cadenza in the first movement. The orchestra accompanied nicely, with especially nice oboe contributions in the Intermezzo. Gerstein seemed to catch Gardner off guard many times, as in the coda of the first movement and the più mosso episodes in the finale, where the pianist's exaggerated and strict accelerations were muddled by the conductor's measures-long adjustment to the new tempi.

After intermission, Gardner impressed in Symphonic Dances. The first movement's outer sections were taut and impulsive, featuring excellent rhythmic precision from the mammoth orchestral forces. The central woodwind episode was haunting, with especially piquant offerings from the saxophone. Gardner's rubato in the second movement waltz at times seemed a bit manufactured, but the woodwinds' will-o'-the-wisp figures and strings' eery tremolos were finely placed and gave the movement the perfect atmosphere. The episodic nature of the final movement is difficult to overcome. The quick sections were impressively played, with pointed, precise rhythmic unisons and wonderful coordination during the composer's rhythmic games in the coda. Gardner and the orchestra made the entire piece sound easy, which is most certainly isn't, and at times one missed a sense of abandon and danger in the performance. If Gardner is "in the running" to be Hans Graf's successor, the question is if he is a conductor willing to take interpretive risks and step outside the box.

Marcus Karl Maroney

|