|

Back

Transcendental Glass New York

The Metropolitan Opera

11/04/2011 - & November 8, 12, 15, 19, 26*, December 1, 2011

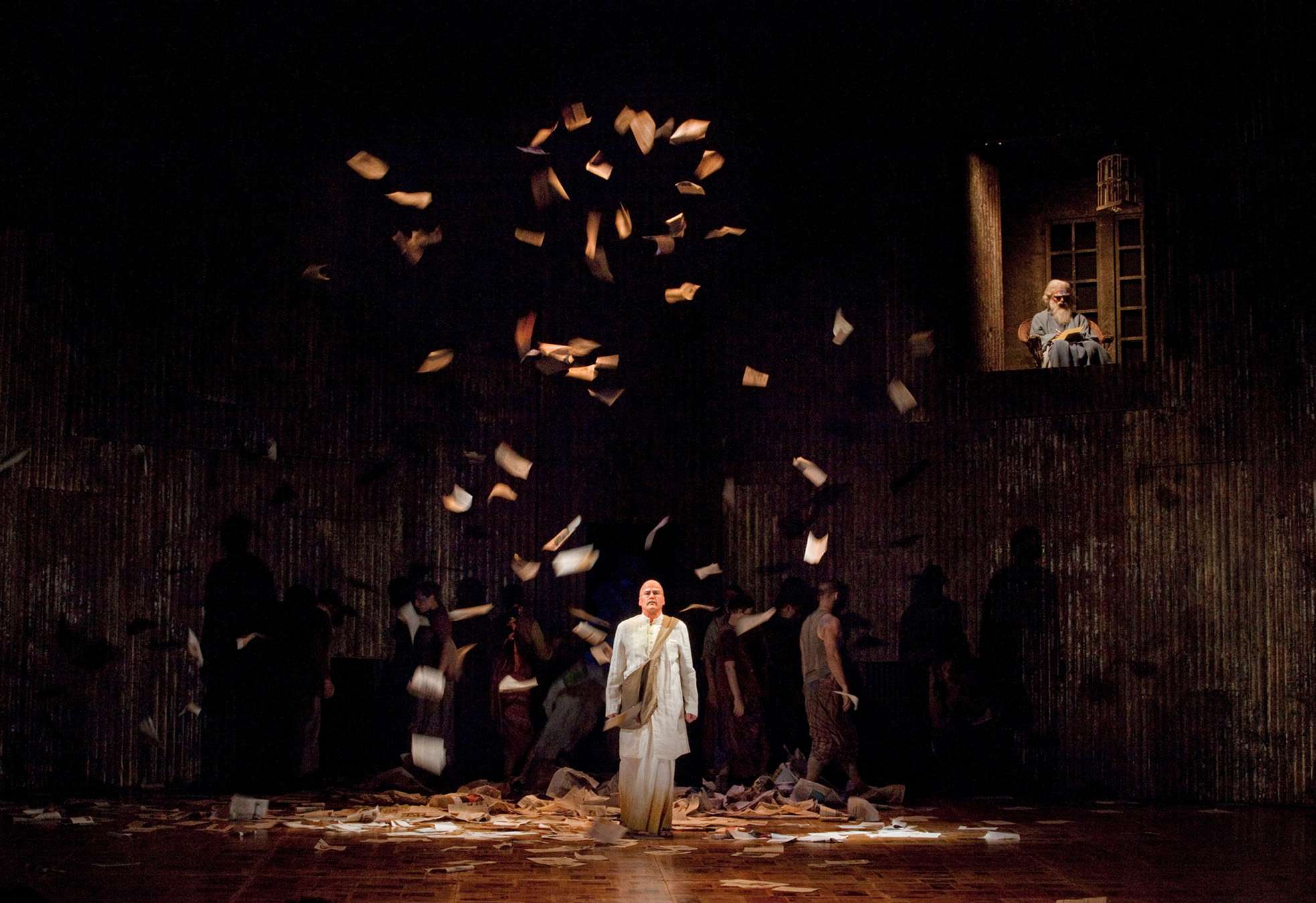

Philip Glass: Satyagraha

Richard Croft (M.K. Gandhi), Rachelle Durkin (Miss Schlesen), Molly Fillmore (Mrs. Naido), Maria Zifchak (Kasturbai), Kim Josephson (Mr. Kallenbach), Alfred Walker (Parsi Rustomji), Mary Phillips (Mrs. Alexander), Bradley Garvin (Prince Arjuna), Richard Bernstein (Lord Krishna)

Metropolitan Opera Chorus, Donald Palumbo (Chorus Master), Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, Dante Anzolini (Conductor)

Phelim McDermott (Production), Julian Crouch (Associate Director and Set Design), Kevin Pollard Costume Design), Paule Constable (Lighting Design), Leo Warner and Mark Grimmer for 59 Productions (Video Design)

(© Cory Weaver/The Metropolitan Opera)

Philip Glass’s Satyagraha premiered in 1980 in Rotterdam. It first came to the Met in 2008 via the English National Opera as a co-production – part of an artistic collaboration between the two companies, which began with Anthony Minghella’s visually stunning Madama Butterfly and continues this season with Gounod’s Faust. Revived at the ENO last season, it has returned to the Met in triumph.

The libretto by Constance DeJong was adapted from the Bhagavad Gita. Indeed, the entire opera is sung in Sanskrit and, uniquely for the Met, there were no translations except for occasional aphoristic projections on the set itself. The opera has no real narrative but it does have a subject – the development of Gandhi’s philosophy of peaceful protest during his years in South Africa. While he was there, he founded a newspaper, Indian Opinion, and organized the oppressed into a powerful moral force that had to be taken seriously by the British colonial authorities. Some sense of the raw hatred engendered by Gandhi’s demand for justice is powerfully conveyed in the second act where huge puppets with distorted faces loom over him as he is taunted by a grotesquely dressed crowd of bigots. He is saved by one woman, dressed in white, who shields him with a large umbrella. She is, of course, a symbol of those whites in South Africa who were morally outraged by the injustices perpetrated by the government at the time and by later governments under apartheid.

R. Croft (© Cory Weaver/The Metropolitan Opera)

The Sanskrit libretto, as well as the overlooking figures of Tolstoy, Tagore and Martin Luther King, act as metaphors evoking the evolution of a moral philosophy as part of a universal struggle, rather than driving plot or focusing on the story of the specific characters. The music makes use of minimal means hypnotically employed, with repeated figures in the orchestra and the vocal line of both the chorus and the soloists. The opera takes place in a sort of metaphysical time, rather than linear time. The music is marked by extended repetitions of simple figures, at times, such as the last aria, just a reiterated scale. The audience becomes submerged in a sea of time, like a pebble on the waves. It’s as if we are experiencing the life and more importantly the growing awareness and spiritual commitment of Gandhi through his own consciousness. In the first act, we see a scene from the Bhagavad Gita as the god Krishna debates the morality of conflict and warriors prepare for battle. This sets up a sense of Gandhi’s struggle being a chapter in an eternal struggle – in both an exterior sense - championing the cause of justice for the world’s oppressed, and internally – as a call to turn idealism into committed action. The libretto is structured around four anchors – the aforementioned Bhagavad Gita and three individuals, two of whom (Tolstoy and Tagore) inspired Gandhi and one (Martin Luther King) who took up his struggle for equal justice under law achieved by peaceful means.

The production by Phelim McDermott and Julian Crouch was quite simply the best I have ever seen at the Met or, indeed, at any opera house. The vast Met stage was virtually bare – framed with a curved wall of corrugated iron, into which were cut doors and windows. In these windows there appeared first Tolstoy and then Tagore and finally Dr. King, who, with his back to the audience, waived to an unseen crowd. The video projections were stunning as was the lighting. The costumes were splendid. Particularly memorable were the over the top outfits of the white South Africans. But by far the best part of the production was the inspired use of puppets manipulated with enormous panache and expertise by the appropriately named Skills Ensemble (a group of acrobats and aerialists).

With the central character, on stage for virtually the entire evening, a marvelous voice is but one requirement. A singer portraying Gandhi must embody his inner stillness, his commitment, and his quiet dignity in the face of humiliation. Richard Croft gave an extraordinary performance. He sang with the clarion tone we have heard so often at the Met. But he also managed to capture much more than our attention; he drew us into some universal consciousness and elicited a kind of shared purpose.

The other singers were splendid. Among the women I would single out the rich voiced Molly Fillmore (who recently made her Met debut as one of the Walküre). And among the men, two bass baritones, Alfred Walker and Richard Bernstein. Bernstein is a comprimario at the Met. In any other house, he would be playing lead roles. (Read here). As Krishna, his rich, compelling voice brought the requisite aura of power and grace to the blue god as he launched mankind on this moral journey.

There are no words of praise sufficient for the Met Chorus, who are as versatile and they are talented and committed. Conductor, Dante Anzolini, along with Richard Croft, wove a poignant spell, drawing a transcendent reading from the Met Orchestra. As the house lights came up for the deafening applause which greeted the cast, conductor and the composer, I felt a palpable shock at reentering the mundane and conflict-ridden world as we know it. But we don’t have long to wait until McDermott and Crouch unleash their creative talents on another Met production – the baroque pastiche, The Enchanted Island, which opens on New Year’s Eve.

Arlene Judith Klotzko

|