|

Back

Lightning strikes but not all are struck Lucerne

Kultur- und Kongresszentrum Luzern

05/21/2011 -

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Oboe Concerto, KV 314

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 1 "Titan"

Emanuel Abbühl (oboe)

London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev (conductor)

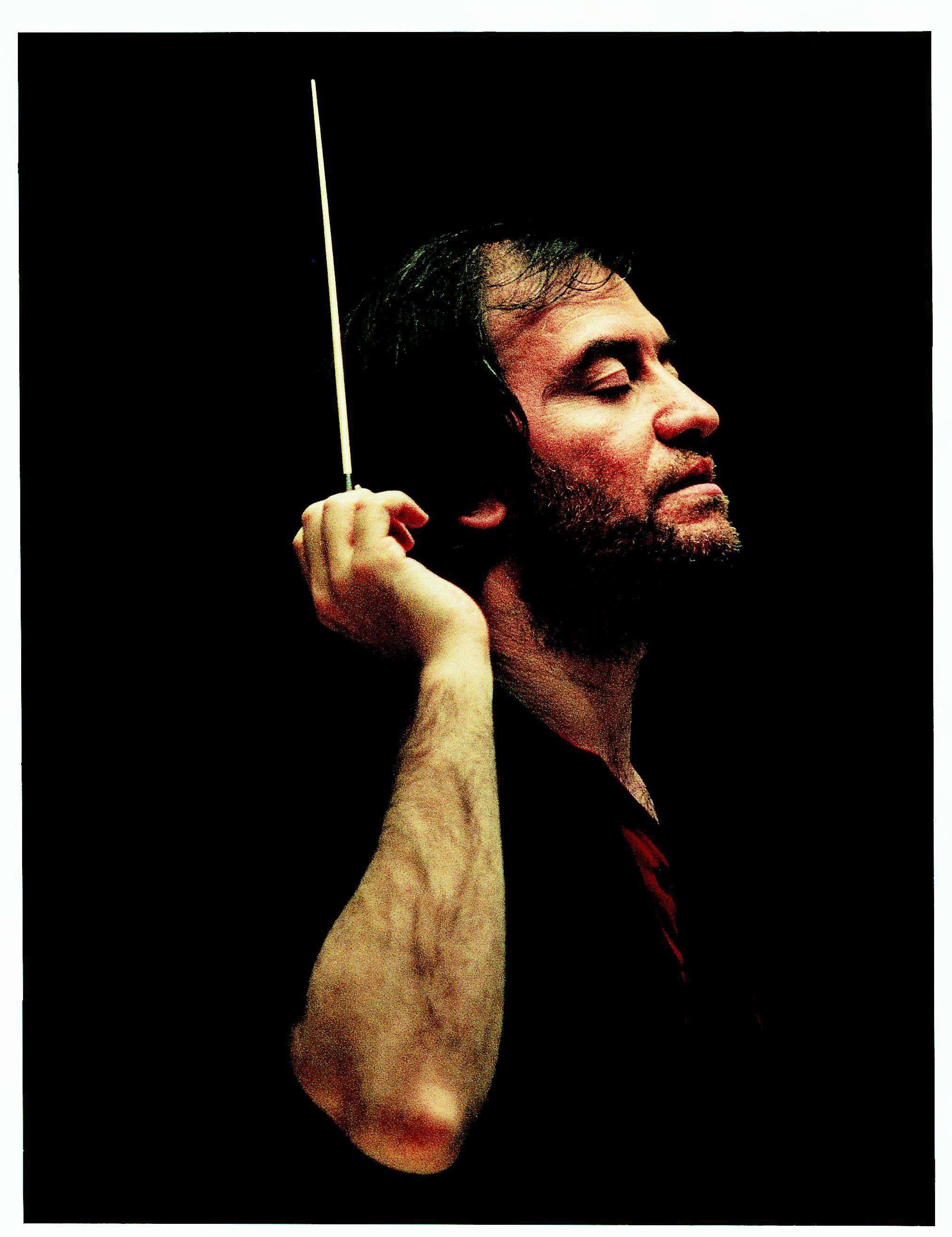

V. Gergiev

Valery Gergiev’s Mahler concerts, with the London Symphony Orchestra, seem to have divided opinions sharply over recent years. In the “Financial Times”, Andrew Clark wrote that “the finale [of the First Symphony] summed up the ills of Gergiev’s cycle – oases of exaggerated stillness rubbing shoulders with outbursts of congested noise, as if Shostakovich had influenced Mahler rather than the other way”. Conversely, Martin Kettle, in “The Guardian”, was enthusiastic, “If you like your Mahler visceral, spine-tingling and dangerous, this was for you.”

It was therefore with a fair degree of trepidation that I ventured forth to Lucerne to hear Gergiev’s very individual view of this symphony. It was certainly tense and neurotic with little Viennese beauty, but I was impressed with the result. After all, Mahler’s early work shocked the audience of his day.

Gergiev starts the symphony with characterful woodwind calls and trumpet fanfares. Gergiev then takes the main part of the movement relatively swiftly. There was some mellifluous oboe and clarinet playing in the development section (the long-standing Principal clarinet is no less that Neville Marriner’s son, Andrew), and a veritable explosion of sound as the movement drew to its impressive conclusion.

Gergiev’s opening tempo for the second movement Scherzo was broad and gradually increased speed as the movement progressed. He and his string sections were most delicate in the central section.

The third movement normally starts with a muted solo double bass intoning the children’s nursery tune Frère Jacques. However, Gergiev chooses to have the melody played by all of the basses. This derives, my research reveals, from the 1989 Critical Edition of the International Gustav Mahler Society, an amendment some Mahler scholars appear to consider spurious. Whatever the merits of the Edition, the provision of tutti double basses gives a feel that is very different to that conjured by the solo instrument.

The “LSO Live” recording has a dramatic photo of forked lightning on the cover. The turbulent opening of the final movement, marked “Stürmisch bewegt”, was suitably electric and the song-like second subject gained utmost concentration from the string section. As the symphony drew to its close, Gergiev summoned the necessary volume from the orchestra. With its frenzied strings, hard-edged brass, and violent timpani, was the conclusion, perhaps, brash rather than triumphant?

In summary, Gergiev’s idiosyncratic interpretation of the symphony succeeds – for the most part – and is highly individualistic. Gergiev draws out staccato and accents with vigour. It is probably not everyone’s cup of tea.

My review of the Mozart Oboe Concerto appears in yesterday’s review of the LSO concert in Zurich.

John Rhodes

|