|

Back

Intriguing Discoveries Toronto

Roy Thomson Hall/George Weston Recital Hall*

04/09/2011 - and April 10*, 2011

Antonín Dvorák: Carnaval Overture, Op. 92

Erwin Schulhoff: Piano Concerto, Op. 11

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major “Eroica”, Op. 55

Orion Weiss (Piano)

The Toronto Symphony Orchestra, James Conlon (Conductor)

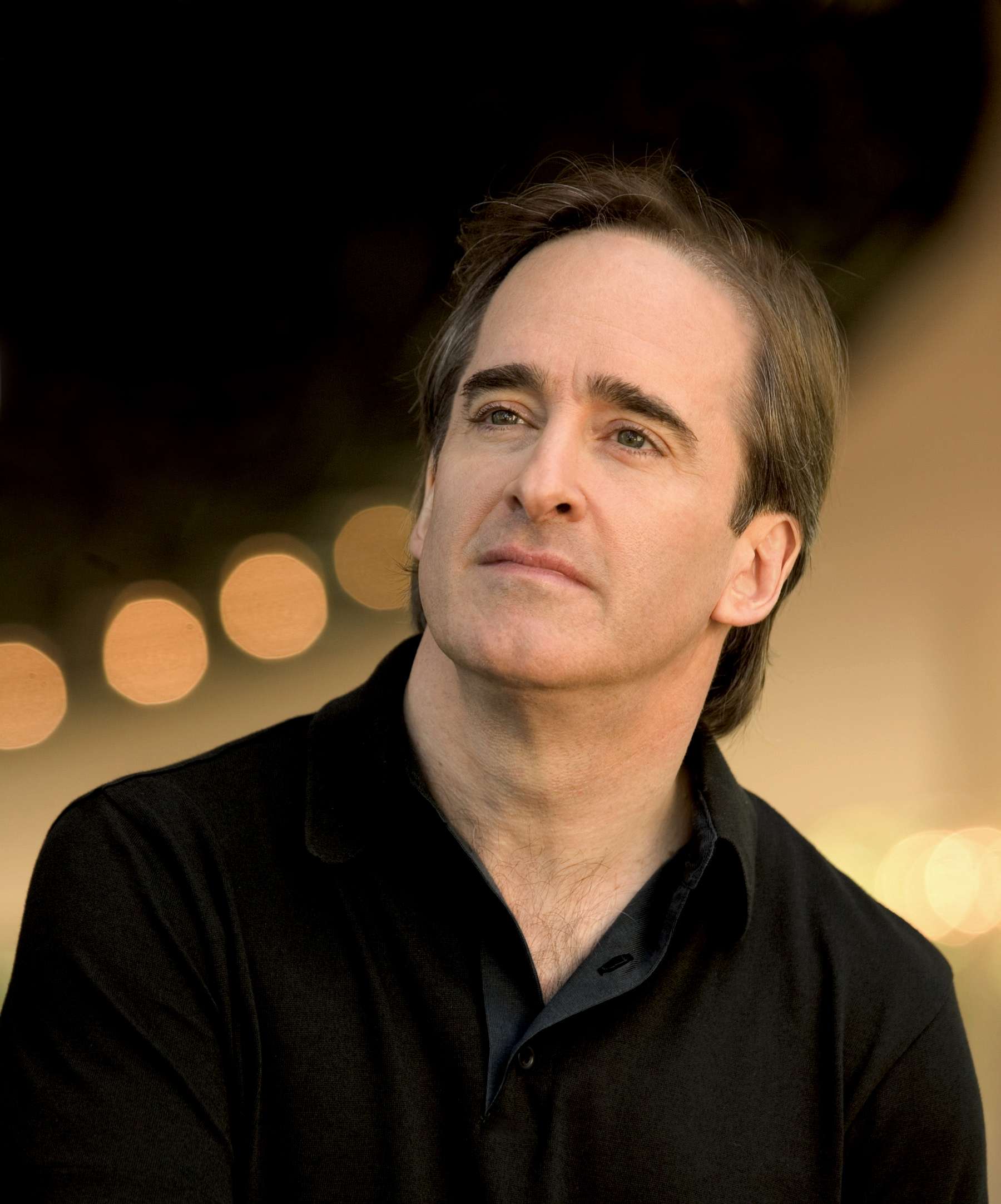

J. Conlon (Courtesy of the Ravinia Festival)

James Conlon made a few appearances with the TSO between 1977 and 1980. His adventuresome career since then has led him (among other activities) to champion composers whose works were suppressed by the nazis – thus the Schulhoff piano concerto on this program.

Guest conducting an unfamiliar orchestra is quite a challenge, especially when the two performances take place in distinctly different venues. Saturday night’s concert was in the TSO’s regular auditorium, the 2630-seat Roy Thomson Hall in downtown Toronto. Sunday afternoon found them in the 1030-seat George Weston Recital Hall in the former suburb of North York (now part of the city). The Weston is noted for its warm, intimate acoustic. It’s an ideal venue for song recitals (it’s also the home base for one of Toronto’s several community orchestras, the Toronto Philharmonia.)

The one piece that seemed too large-scale for the Weston was the opener, Dvorák’s Carnaval concert overture. Conlon’s brisk attack on both its opening and closing sections was nicely contrasted with the dream-like central section. It certainly made the audience sit up and take notice, even if the sound blared at moments.

Erwin Schulhoff (1894-1942) was one of many composers not only suppressed by the Nazis but whose music got sidelined when the dominant currents in musical development assumed different directions. Mr. Conlon treated us to an informative introduction to the composer and, specifically, to his first piano concerto. Schulhoff, like Mahler, was a German-speaking Jew from the Czech lands of the Austrian Empire. At the age of seven he impressed Dvorák (not easily impressed by the many “talented” youngsters paraded before him), and later had a grand total of two lessons with Claude Debussy. His first piano concerto was completed in 1913, just as he finished musical studies in Cologne.

We can’t really say this specific work was suppressed nor bypassed; more accurately it was left behind by the composer himself. When World War I broke out he was conscripted into the Austrian army and was eventually wounded. Upon resuming composing, he quickly adopted a new style – and kept adapting new approaches as he went along. He never pursued a performance of this early work, in spite of experiencing a good deal of success as a performer and composer with some 120 works to his credit.

Schulhoff veered from composing in a folk-flavoured idiom toward jazz (even before Milhaud’s landmark La Création du Monde of 1923). He composed an all-silent work long before John Cage’s famous similar effort. One influence he avoided was Schoenberg’s atonality (although he had heard Pierrot Lunaire, one of the sensations of the era, as he composed his First Piano Concerto).

Lotte Lenya once dryly remarked that Kurt Weill had ended his partnership with Bertolt Brecht because he didn’t want to set the Communist Manifesto to music. Amazingly enough, Erwin Schulhoff did create a cantata to portions of it when he became enamoured of communism in the early 1930s. He subsequently took steps toward moving to the USSR, attaining soviet citizenship just before the German invasion of the USSR in June of 1941. A resident of German-controlled Bohemia at the time, he was arrested and detained as an enemy alien. He died of TB in Weissenberg, Bavaria in 1942.

So what is this concerto like? For one thing, it sounds like a young man’s work. It’s tonal and melodic, with a crisp, jaunty opening. There is a keyboard-striding solo section in the first movement and it can be said that some of the musical material goes on a bit longer than it ideally should. The second movement is ruminative, mostly for piano solo with some interchange with solo viola and wind instruments. The third movement has a lively, scampering quality, then a rather Gershwinesque solo, before storming along to a big finale. All in all, an engaging work. It doesn’t sound like warmed-over anything else (Dvorák, Strauss, Debussy or whatever). It was adroitly played by debuting pianist Orion Weiss (check out his “wacky, witty, worldly, wonderful, never woebegone website”).

The program’s big work was one of the towering landmarks of the symphonic repertory, Beethoven’s third symphony, the Eroica. The players numbered about 60, which turned out to be just right for a full-bodied sonic experience in a hall where music really resounds. A brief tempo disagreement with the cellists didn’t mar an interpretation that was well-judged (masterful in fact) and with as much momentum as one would wish without the music ever seeming rushed. An ideal preceeding piece would have been perhaps a late symphony by Haydn; this would help bring out the startling dissonances that Beethoven introduces in the first movement.

It’s actually quite an achievement to make this frequently performed piece seem so fresh. Let’s hope James Conlon returns before another 31 years elapse.

Michael Johnson

|