|

Back

Sex, Violins and Tales of the Baroque New York

Highline Ballroom

04/06/2010 -

Music by Vivaldi, Westhoff, Falconieri, Leclair, Ortiz, Handel etc.

Daniel Hope, Erin Keefe (Violins), John Hadfield (Percussion), Jeffrey Grossman (Harpsichord), Joshua Romans (Cello), Charles Weaver (Guitar, Theorbo)

D. Hope (© Marco Borggreve)

The choice last night was not agonizing. On this beatific Spring day, would I go to hear the four-square, pretty (and pretty good) pieties of Mendelssohn’s Elijah? Or should I take a chance, go to a 10th Avenue ballroom and listen to a young British violinist perform totally unknown–and certainly unpredictable–music from the Baroque period?

The answer was obvious I don’t know what Daniel Hope put on his most recent album, "Air:A Baroque Journey", but it couldn’t he have as entertaining as the one-hour concert of Baroque music last night at Holliman Ballroom.

What’s that? you ask. Entertaining?. Well…yes. Music of the Baroque and late Renaissance was not all B Minor Mass and Messiah and solo cello suites. The Renaissance was exactly that: a rebirth of painting, politics, architecture, theater-opera and music. The Baroque period was filled with weird decorations, original musical sculpture, originality without too many regulations. (The regulations were written in long treatises which, like Aristotle’s dramatic unities, were meant to be broken.)

String instruments were being invented (or taken from the Spanish Moors), claviers were being well-tempered, and tunes from the belfries, naves, cathedrals and streets were echoing back and forth throughout Europe. The strict rules of the Church, represented by Palestrina, were being broken by the secular composers who wanted to inspire rather than sanctify. String players who had played background music now were coming to the forefront, not for the Bishopric but for the far-from-holy, fun-loving somewhat decadent aristocrats and (in Venice, at least), the common folk.

That, at least, is what Daniel Hope was generating for an audience exhibiting the enthusiasm usually found only in Le Poisson Rouge.

Mr. Hope is a master violinist (more on that later), but in such an atmosphere, his oral repartee was spontaneous, and was at least half the fun. This writer had known of Vivaldi’s dalliances at the girls school, and the murder of Leclair, but Mr. Hope all too ready to offer the anecdotes–more prurient than pure–about those crazy composers who dashed around Europe, fornicating, drinking themselves to death, being woken in the middle of the night by Louis XIV to play an air or two and showing skills which are magical to this day.

His comments were amusing, peripherally technical, but never condescending. (Though one or two were superannuated, like comparing the promiscuous subject of Greensleeves to Monica Lewinsky.)

His choices of music could be considered eclectic or esoteric, but never erudite. Take one Andrea Falconieri, seducer, drinker and the most risk-taking violinist. Not only was he the first “lyrical” violinist (with a short work called “The Suave Melody”, but he composed another piece played here with repetitions resembling those of Philip Glass.

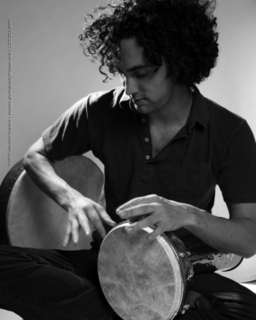

J. Hadfield (© Jennifer Sexsion)

Then we have Paul von Westhoff. In the court of Louix XIV, he composed a work celebrating “The War of Jenkins’s Ear”, a battle between England and France. This was loud, highly military (with incredible drumming on a calfskin military drum by John Hadfield), and brazen.

Mr. Hope has an astonishingly easy way with his violin. Most of the music he played had techniques which were developed for the particular music, and he gave it the off-the-cuff spontaneity which the composers must have felt.

“Oh, look,” would say Mr. Von Westhoff, “if we press down a pair of strings, we can make two tones at once. We can save money on a harpsichord player!” Or, “If we pluck the strings we can make them sound like a lute, so we can get rid of that ungainly theorbo instrument.”

The works were mainly unfamiliar, but Mr. Hope did have a lovely set of variations on La Follia, played an encore of Bach’s Air (dedicated to his musician father, in the audience) and a bit of Handel.

Mr. Hope didn’t play alone. In fact, when introducing percussionist John Hadfield, he had to tell the skeptical listeners that, yes, drums were indeed part of the music. He had a second violin player, Erin Keefe, who played “dueling strings” in another Falconieri, and the other musicians listed above. They all seemed to be having fun.

And that was how the music was perceived. Those expecting bewigged, stern-faced organ-playing sacred pieces would have been disappointed. Certainly those works were prevalent, and certainly they have come to represent Baroque music in our time.

But Mr. Hope wanted to show the Renaissance and Baroque in a different light, very much like our own times. Those cages which segregated “serious” from “street” or “structured” from “improvised” disappeared in those heady times, as they have from our own times. Yes, one peripatetic composer found a Scots folk song, but he constructed it with a series of the most intricate variations, bringing together the light and the fantastic.

For, as Mr. Hope showed well, in those days music could heal the troubled soul, make the feet dance, and–even as the dour Schopenhauer said–“become joy, sorrow, pain and delight in itself.”

Harry Rolnick

|