|

Back

Orchestral Journey for Ears and Eyes Houston

Jones Hall

01/21/2010 - & Jan. 23, 24, 2010

Igor Stravinsky: Scherzo fantastique, Op. 3

Henri Dutilleux: Timbres, espace, mouvement

Gustav Holst: The Planets, Op. 32

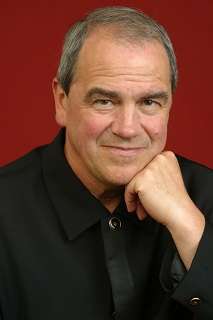

Houston Symphony Orchestra, Hans Graf (conductor)

H. Graf (© Christian Steiner)

Stravinskyís Scherzo fantastique, with its focus on augmented harmonies and watered-down, Tchaikovsky-esque melody in the center of the work, is a letdown. The composer hadnít yet learned to create the timbral mystery and rhythmic impetus that would emerge in his next orchestral essay, Fireworks, and make the music of his three early Russian ballets so memorable. The lack of low brass and the constant tossing about of small musical gestures make the work far too similar to "Mercury" from the Holst suite, yet, in a stunning upset, Holst achieves a better final result in that sparkling movement, scoring points for brevity, momentum and the wise choice to omit an unconvincing, melancholy central episode. Even in Stravinskyís own recording of the Scherzo, taken a few notches quicker than Grafís performance, the energy has a tendency to flag. The HSO is without a doubt a crackerjack ensemble whose members can toss off the many challenging passages in their sleep, and the performance was excellent from a technical standpoint, but didnít quite excite like a good curtain-raiser should.

Henri Dutilleux would be my nomination for greatest living composer, and Graf should be applauded for programming his music in Houston. The composerís sensitivity to timbre, entrancing harmonic language that is both magnetic and challenging, and diligence in working for years (sometimes decades) to produce the perfect final result have given us a small but extraordinarily superlative catalog of pieces stretching back nearly sixty years. The dark-hued Timbres, espace, mouvement, a masterpiece of orchestral deployment, was a great choice to contrast with the fluffy Stravinsky work. Sadly, the time spent rearranging the stage for the piece immediately raised eyebrows. Why Hans Graf didnít respect the composerís very specific stage instructions is a mystery. Dutilleux prescribes that the all-important cello section be arranged in one row around the conductor at the front of the orchestra, and that they be separated by one row each of woodwinds and brass from the double basses and percussion, which are to be arranged in a row on the back of the stage. Graf had the cellos in two rows to his left, the double basses at the front of the stage to his right, and, again contrary to the composerís specifications, reversed the position of the percussionists and timpani.

This might seem like nitpicking, but Dutilleux didnít request this layout arbitrarily. The percussionists should be on the same side of the stage as the harp and celesta (left of the conductor and opposite the double basses) because they play similar roles: the crotales and glockenspiel function as a more insistent celesta, emphasizing wind and string articulation; the marimba provides a different shade of color in paroxysmal solos that it shares with the harp; the multiple tam-tams and suspended cymbals create a blanket of resonance that, when paired with similar gestures from the double basses (which should be in the back, to the conductorís right), enrobe and support the orchestra from both sides. Likewise, Dutilleux composes numerous left-to-right panning effects in the central interlude for the twelve cellos that only work if theyíre seated as specified in the score. This isnít to say that the piece doesnít work if these instructions arenít followed, and the majority of the audience likely had no idea that any violation of compositional intent was taking place.

Again, the orchestra executed the piece with masterful technique. The opening descent through the winds and high brass was excellently tuned and blended. The nebulous oboe díamore and muted trumpet solos in the first movement and oboe and alto flute solos in the second movement had the wonderful wispy quality clearly inspired by the shapes of van Goghís Starry Night. The cello interlude spoke to the depth of the orchestra, with every player producing wonderful tone and spot-on balance and intonation in the many complex chords. Complex rhythmic unisons across the orchestra were consistently in sync.

The shape of the piece is all about moving into and out of unisons, and these should be powerful moments whether subdued or exuberant. Graf molded such gestures nicely in soft passages, but seemed reticent in louder passages. The endings of the two major sections of the piece werenít given their due dynamically, especially the ultimate climax, where rolled tam-tam and heavy brass should overwhelm the listener. Graf stopped the orchestra at about mezzo-forte instead of achieving a true fortississimo conclusion.

The Planets was presented with a new video designed in cooperation with NASA. ďAn HD OdysseyĒ consisted mostly of impressive postcard-like images projected alongside each movement, sweeping from panoramic vistas to extreme close-ups. There were some stunning animated moments that paired up nicely with the music, such as weather movies that danced in perfect time with the waltz-like section of "Jupiter." The visual aspect enhanced a solid performance of the suite. "Mars" and "Jupiter" were the most dazzling, the former especially receiving a reading of vehemence and thrust building to an enormous, no holds barred climax. "Jupiter" was taken at a quick clip, dancing along all the more jubilantly, and the famous central melody was gloriously rendered. "Mercury" and "Uranus" had a few tenuous spots, but "Venus" was strikingly hushed, the women of the HSO chorus emerging imperceptibly and singing their eerie dissonances expertly. The combined audio-visual final project was a delight. The sustained applause was rewarded with an encore, Stravinskyís Fireworks, which would have worked wonderfully as the programís opener.

Marcus Karl Maroney

|