|

Back

Show-Biz Diabolique New York

Park Avenue Armory

12/16/2009 - & Dec. 17*, 18, 19, 20, 2009

Heiner Goebbels: Stifters Dinge (Stifter’s Things) (U.S. premiere)

Heiner Goebbels (conception, music, and direction), Klaus Grünberg (set design, lighting, and video), Hubert Machnik (programming), Willi Bopp (sound design), Matthias Mohr (assistant)

“New Visions of Lincoln Center”, Presented in association with Park Avenue Armory.Originally produced by Théâtre de Vidy, Spielzeit’europa/Berliner Festspiele, Grand Théâtre de la Ville de Luxembourg, schauspielfrankfurt, T & M-Théâtre de Genevilliers/CDN, and Pour-cent culturel Migros. Co-commissioned by Artangel London.

H. Goebbels (© Wonge Bergmann)

Four centuries ago, Heiner Goebbels would have been burned as a sorcerer, or Faust might have summoned him up from the depths of hell to show his demonic powers. Some 80 years ago, Max Reinhardt produced stageplays just as gigantic, but they were products of the Industrial Age. Herr Goebbels has effects which are unfathomable.

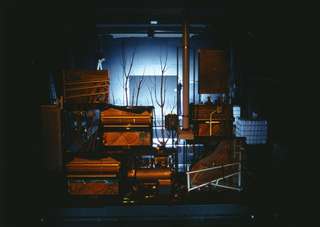

What we have this week in the Park Avenue Armory is a stage about a quarter-mile long. The audience is escorted in to see three huge empty rectangles, with some Plexiglass walls on one side. Two stagehands–the only humans in the entire production–pour what looks like rice or ice into sifters which are then winnowed (or sifted) onto the rectangle to make a kind of pool. Through the next 75 minutes, these “pools” , through the use of lights, underwater jets and positively mystifying procedures, are turned into ice rectangles, snow rectangles, rectangles with salamander, with steam, with ducks, with rain, with water or sometimes simply dark and foreboding.

Now at the back of the stage is a huge reproduction of a 17th Century nature painting. Over the next 20 minutes, the painting turns all kinds of colors, shapes, sizes and finally into a series of clouds.

Pianos without players (© Mario del Curto)

Next on the lineup are three huge muslin curtains descending between the rectangles. They rustle, they have images which disappear. And finally, the pièce de résistance, the curtain in the back rising upon five old pianos, their bodies exposed. Some are mechanical, some played with Rube Goldberg-type machines. The pianos play different music (see below), and sometimes they roll on rails right towards us in the audience before rolling back.

And now the aural theater. We begin with electronic pianos rumbling in the background, go onto a Papuan chant recorded in 1905, resonating through the Armory. The pianos plays first two leading notes from Bach’s Fantasia and Fugue, then the entire slow movement from the Italian Concerto. After this is jazz, played amazingly by the pianos in rippling octaves one after the other, and a video of a shaking brass instrument. This is followed by Columbian Indians chanting, an old Greek song, offering good luck to fishermen.

Literarily, the title gives it away. Stifter’s Things come from the writing of an early 19th Century Austrian nature poet. But very few of his “things” are mentioned. Instead, we have a conversation with the late Claude Levi-Strauss about the inhumanity of humanity. (The English sur-titles on the curtains take the place of a picture by Paulo Ucello in the original.) Then some words by William Burroughs and Malcolm X) and finally some more words by Mr. Stifter.

At this point, the lights go dark and then on. And then Herr Goebbels steps out on stage for a modest bow.

I only describe things this way because the effect of this… er, stage work cum music work cum literary work, while stupendous by itself, does not really have much to do with an artistic production. In any art, whether Gregorian Chant, or Picasso or Gone With the Wind or King Lear or a two-minute piece by Anton Webern, we must feel that the continuation is inevitable, that the writer/composer/artist had no other choice than the note or brush-stroke or dialogue. And while this may be a semblance of truth, it is a necessary semblance. (In aleatory improvisation, that rule is not followed, by definition. But Stifter’s Things is the opposite of improvisation.) Here, though, we are looking for the next illusion, the next trick, the incredible sound system making a 1905 chant sound like it was sung yesterday, the astounding mechanical pianos where we see the mechanism at work. But nothing is unavoidable. Herr Goebbels could have run the show backwards, and it would have had the same effect.

Mind you, I was thrilled to have gone. When Lincoln Centre presents “New Visions”, they aren’t kidding. Each of these productions has a surprise, an effect of magic, and, yes, a new way to look at what we may have known before.

Herr Goebbels has achieved some impossible effects here. And when the audience walked out to the “stage” (the floor of the Armory) to examine the pools and the pianos, I took a cursory glance and exited. Those illusions, whether “art” or “magic” or Divinely Inspired Transcendental Show Biz did have the effect of genius at work. A mad genius, and a genius whose poetry is all too personal. No revelations, no epiphanies, no enlightenment. But the ultimate not only in demonic sorcery but a diabolically good show.

Harry Rolnick

|