|

Back

Musica Incognita New York

Good Shepherd Church

05/01/2023 -

Sergei Prokofiev: Romeo and Juliet, Op. 64: “The Montagues and Capulets” (Arranged for violin and piano by D. Grjunes)

Giya Kancheli: Ninna Nanna per Anna

Mieczyslaw Weinberg: String Trio, Op. 48

Alexander Naumovich Tsfasman: Intermezzo

Myroslav Skoryk: Melody in A minor for String Quartet

Dmitri Shostakovich: Piano Quintet in G Minor, Op. 57

Jupiter Symphony Chamber Players: Charles Neidich (Clarinet), Jennifer Frautschi, Isabelle Ai Durrenberger (Violins), Paul Neubauer (Viola), Ani Aznavoorian (Cello), Adam Golka (Piano)

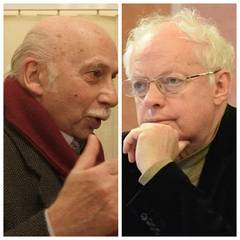

C. Neidich/J. Frautschi

“Real music is always revolutionary, for it cements the ranks of the people; it arouses them and leads them onward.”

Dmitri Shostakovich

Of New York’s manifold musical secrets, the Jupiter Symphony Players is among the most singular. Though I shouldn’t say “secret”. Each of their monthly afternoon concerts have packed houses, as do the repeats that evening. Even more important is their choice of music For more than two decades, their concerts, a block from Lincoln Center at Good Shepherd Church, has gone far far afield from the usual Haydn-Mozart-Dvorák page‑turners. In fact, looking over the series this year, I saw a list of virtually unknown composers of the past 200 years.

Taffanel? Klughardt? Farrenc? Reber? (No, not Fauré, not Reger). That’s was just the beginning. And while this afternoon had the usual names (Prokofiev, Shostakovich), the names Skoryk, and Tsfasman were musica incognita to this ignoramus.

Most essential of all the Jupiter Symphony Chamber Players attracts players at the top of the New York artist list. And they obviously enjoy their ensembles, and their new music.

Not that the excerpts from Romeo and Juliet were unknown. But this arrangement for violin and piano was played with orchestral gymnastics by two soloists here.

The next three pieces came from three acrimonious “neighbors” of Russia. Mieczyslaw Weinberg was born in Poland, fled the Germans to Russia, settled in Tashkent and returned to Moscow and Saint Petersburg. This Trio was typical, a combination of Russian, Moldovan and above all, Jewish ethnic music in one delightful bundle.

Kancheli was purposely more childish. This Ninna Nanna per Anna was serious, if nursery style melodies can be called childish. But it was also far far more complex, the melodies proceeding, backing off, always near-accessible, yet with mysteries among the quartet and the always incredible clarinet by Charles Neidich.

Finally, a Ukrainian Melody by Myroslav Skoryk, apparently a “spiritual anthem” from the Republic. Not as magical as the other works at first hearing. But one could always give it another listen.

G. Kancheli/M. Skoryk

The final two works were fascinating. The first was from a total unknown, the second by the most famous Russian (and sometimes Soviet) composer of them all.

Alexander Naumovich Tsfasman was a jazzman at a time when jazz was more less verboten. From the Intermezzo this afternoon, he was a self‑assured composer whose instrument here–and whose cool (for the time) notes could have been written for the Benny Goodman trio or quartet.

The performer was once again Charles Neidich, but in a different guise. His Kancheli piece had been a serious chamber work (by another composer who loved jazz), and he worked at it with serious virtuosity. Tsfaman’s Intermezzo was pure 1930’s style, non-African-American jazz, played with an easiness, a fluidity, an unthreatening jazzy melody, ending with Mr. Neidich on the highest non‑harmonic clarinet note. It was a delight.

The Shostakovich Piano Quintet, composed three years after the Tsfasman, is one of the greatest chamber works of the 20th Century. And pianist Adam Golka, with a quartet headed by Jennifer Frautschi, was anything but cool. The energy, the desolation, the violent mood swings are all expressive of the composer at his most inspired.

The performance this afternoon was, to say the least, biting. The opening piano chords by Adam Golka set the stage for an adventure into a great mind. In fact, the ending of that movement and the opening of the fugue were both breathtaking.

Nor could I single out any individual artist. While the chamber-music masses were relatively great, Shostakovich used each player to run into the next player. For the first time, I realized how the composer didn’t have a single design. By changing each player, one saw a painting of constantly shifting colors.

While Shostakovich didn’t meet Weinberg until many years later, the scherzo was almost Jewish. It was sardonic, it had savage themes. Most of all, each of the strings played hard on their instrument, eschewing even the hint of “pretty” playing.

Ms. Frautschi’s soaring violin was the keynote to the centerpiece slow movement here, and its sorrow was played with such emotional directness, that not even the dancing finale could take away the profundity, the Stygian darkness of this so great work.

Harry Rolnick

|