|

Back

Rafael Payare’s Splendid Debut New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

03/08/2023 - & March 6 (Washington), 9 (Montréal), 2023

Dorothy Chang: Precipice (New York Premiere)

Béla Bartók: Piano Concerto No. 2 in G Major, BB 101

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 5 in C‑sharp minor

Yefim Bronfman (Pianist)

Orchestre symphonique de Montréal, Rafael Payare (Music Director, Conductor)

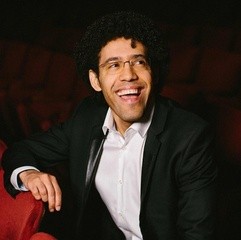

R. Payare (© San Diego Symphony)

“My own idea, of which I have been fully conscious since I found myself as a composer, is the brotherhood of peoples, brother despite all wars and conflicts. I try–to the best of my ability–to serve this idea in my music.”

Béla Bartók

In the last 48 hours, Montréal’s own Yannick Nézet‑Séguin and Montréal’s own Symphony Orchestra have awarded New York an infinitely grander taste of that great city than all their vile ill‑vaunted bagels.

Nézet‑Séguin showed us a rapport with artists and audience, an excitement, an ardor both as conductor and pianist. The Montreal Symphony Orchestra has been first‑class for a long time, shepherded by music directors like Charles Dutoit, Zubin Mehta and Kent Nagano. Last night, under their new conductor, Rafael Payare, they played a most challenging concert with the classiest first‑chair musicianship.

As well as a controversial question about pianist Yefim Bronfman.

Mr. Payare, part of the Venezuelan Music Mafia (just kiddin’) is a mesmeric leader. Like most young conductors with a new orchestra, the 43‑year-old leader leads with broad strokes and athletic visual prowess. The result, in the longest work on the program, Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, was given a pulsing, forward-looking performance. From the first trumpet call by Paul Merkelo (who dominated the music) to that great chorale–in my opinion, the greatest chorale since Bach–Mr. Payare was most expressive.

Obviously, one would be foolish to compare this Fifth with the hundreds of previous performances. The Montréal Symphony Orchestra is releasing their first recording with this piece. It takes much chuzpah to add yet another disk with the massive previous numbers.

Were they taking advantage of this symphony as the centerpiece of the movie Tár? That Fifth could become the new Adagio for Strings in popular taste.

But I prefer to remember the Adagietto as the background for Visconti’s film Death in Venice. And while one should judge music on its own, I cannot possibly listen to that movement without thinking of Thomas Mann’s Aschenbach searching for the angelically beautiful Tadzio in the lanes and over the bridges of the deserted city.

Yet Mr. Payare came near to letting the music speak for itself. Not too much rubato, and just enough sliding portamento tempo allowances to let the strings and harp speak for themselves. Undue sentimentality could lead to mawkishness, and the conductor never allowed that to happen.

This came after a martial opening movement and a terrifically stormy second movement. Here, Mr. Payare, a French horn virtuoso himself, gave all the impetus to the brass. They exploded when necessary, they passed on their tremors to timpani and wind.

These first two movements were not shattering, as some have conducted it. Nor did Mr. Payare overdo its puzzling structures into hysteria. Instead, they became unsettling, unnerving. Never calculated, always felt with intelligence and–above all–gargantuan power.

What to do with the long finale? Following the notes literally, no first‑rate conductor can fail. Mr. Payare, with that first‑rate brass section, drove the movement forward to its tumultuous climax. Yet one must ask whether such propulsion is necessary. That chorale is a repeat from the first movement, yet one must hear it as if the first time. The hints, the cryptic partial measure need to be restrained, need to tantalize the listener before the grand climax, and Mr. Payare engineered the orchestra as he felt it.

Y. Bronfman/D. Chang (© Dario Acosta/Courtesy of the Artist)

The evening seemed to begin with a few measures of Mahler’s First Symphony. No, that isn’t true. But Dorothy Chang’s Precipice began with the twittering bird calls which so resembled the Mahler. After this, though, the ten‑minute work by the accomplished Canadian-American composer continued through some dense, tense orchestral sections, ending in sounds without pitch and a desolate violin and viola solo. Ms. Chang explained in the program notes that it started as an obsequy on climate change, but then evolved into a lamentation on the state of the world in general.

Sigh!

The centerpiece here was Yefim Bronfman’s work on Bartók’s Second Piano Concerto. Work, though, is wrong. Mr. Bronfman gave a sizzling performance, taking in the mystery, the fireworks, the Cimmerian darkness and radiating pyrotechnics.

Where one must ask a birdbrained question: Is Yefim Bronfman the world’s “best” Bartók concerto‑guy? No such adjective is allowed. But Mr. Bronfman has the extreme muscularity, the bouncing playfulness, and the staggering virtuosity to at least put him in the front ranks.

Nothing released the tension, not a single note–whether with orchestra or solo timpani–was not fresh, adventurous or exciting.

The pianist’s Chopin encore was hardly necessary, but played, of course, with silken splendor.

Harry Rolnick

|