|

Back

From Miasmic to Magical New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

05/12/2022 - & May 7, 8, 2022 (Saratoga Springs)

William Grant Still : Dismal Swamp (*)

Carlos Chávez : Piano Concerto

Witold Lutoslawski : Symphonic Variations

Karl Amadeus Hartmann : Symphony No. 1 “Essay for a Requiem”

Deborah Nansteel (mezzo‑soprano), Frank Corliss (*), Gilles Vonsattel (piano)

The Orchestra Now, Leon Botstein (founder & conductor)

D. Nansteel/G. Vonsattel

“Depression Era? Exhilaration Era!”

Anonymous

Leon Botstein never learns his lesson. Give a program with four dazzling compositions, from miasmic to mirthful, four different countries, three dazzling soloists and his own orchestra playing better than they ever did before.

And Carnegie Hall barely was 50 percent full.

Not that this would presumably annoy the conductor. As the heir to Leopold Stokowski’s American Symphony Orchestra, and the founder of last night’s The Orchestra Now (TŌN), he goes his own way. A historian as well as conductor, Mr. Botstein took these four relatively unknown composers and plunked them into a historical era: “New Voices from the 1930s”. The result could have been academically interesting. But the quartet of works, hardly ever heard in New York (this is the 80th Anniversary of the Carnegie Hall American premiere of the Chávez Piano Concerto) and the revelations never ceased.

I had never heard the Chávez Concerto before. Yet before the first measure was halfway done, Swiss‑American pianist Gilles Vonsattel demonstrated with all ten digits that it would scare away the most experienced artist. Specifically, the first three‑quarters of the work was so complex, piercing and unrelenting, it would make Busoni’s Concerto seem like child’s play. Not that “complexity” means difficult to hear. One might not catch the thematic links at first hearing, but the jumps, the subtle Mexican rhythms, and–above all–the agitation and rhythmic pulses were enough to raise any listener’s cerebral blood pressure.

The second movement gave a short hiatus. But the finale (marked Allegro non troppo but played at an unstoppable Presto!) was again genius of both composer and soloist.

Mr. Vonsattel took all the blazing measures as if born to the notes. The miracle of his playing was that one had to make an effort to say this was “virtuosic.” It was incendiary music‑making from beginning to end.

The opening piece titled Dismal Swamp wouldn’t exactly inspire a Fred Astaire tap‑dancing routine. But William Grant Still’s tone‑poem, based on a poem by his wife, was a fascinating picture of moodiness, desolation and later triumph.

This was again a work with piano, but Frank Corliss’s fluid playing was more a dialogue with the orchestra. Towards the middle, Mr. Corliss–a prime exponent of Elliott Carter–showed Still’s dissonant side as a student of Edgar Varèse. Unlike most African-American composers of the 1930s, William Grant Still needed no ethnic reminiscences to make his music live.

Dismal Swamp had the subject of slaves taking refuge in this Virginia bog. But the mood was Impressionistic, filled with contrasting emotions. His single opera has not been performed here recently. If Dismal Swamp is an indication of his originality, it needs to be revived.

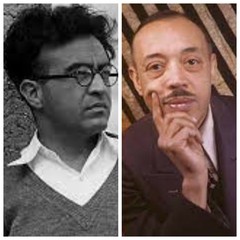

C. Chávez/W. G. Still

After the intermission, Leon Botstein’s TŌN showed it own expertise in the early Lutoslawski Symphonic Variations. Written two years before his more famous Paganini Variations, this work could have been difficult to analyze. Not because of its complexity, but because Lutoslawski’s Bartókian counterpoint was so neat, the rhythms so dazzling (including a sudden 18th Century folk dance) and the color so radiant that the tapestry was filled with far too much.

Mr. Botstein’s other works had been dependent on soloists. Here, from the very first flute theme (played Rebecca Yutunick), TŌN played through the cascades with a sureness and above all a lucidity doing justice to the composer’s youthful athleticism.

The final work was a symphony. It could have been called a Timpany. Karl Amadeus Hartmann’s First Symphony commenced and intermittently continued with a loud and louder timpani solo. This was the far from subtle indication of Hartmann’s feeling in 1935 about the Nazi regime in his native Germany.

Four of the five movements were based on sections of Walt Whitman poems (sung in German). The center movement was purely orchestral.

The greatness here was partly musical–but far more vocal. The Met Opera’s Deborah Nansteel has a liquid mezzo voice which pierced through the various musical forms. At the top of her range, though, her purity, the bell‑like absolute beauty, created an undefinable yet unforgettable aura.

This was that rare programming where nobody could honestly say that one work was “better” than another. Each had its own effulgent environment, and Mr. Botstein’s orchestra offered an uncommon experience.

Harry Rolnick

|