|

Back

Merry Christmas! Happy Honegger! New York

Grace Rainey Auditorium, Metropolitan Museum of Art

12/08/2019 -

“Honegger, Vallotton and The Avant-Garde in Paris”

Arthur Honegger: Symphony No. 1 in C Major

Metropolitan Museum Curator Dita Amory (Speaker)

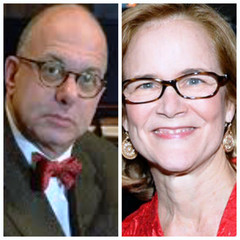

The Orchestra Now (TŌN), Leon Botstein (Speaker, Conductor)

L. Botstein/D. Amory

“To write music is to raise a ladder without a wall to lean it against. There is not scaffolding; the building under construction is held in balance only by the miracle of a kind of internal logic, an innate sense of proportion.”

Arthur Honegger (1892-1955), I Am A Composer (1952)

The Hebrew Festival of Lights is twelve days away. But one cannot doubt the Talmudic perspicacity of Leon Botstein. So if he wished to celebrate Honegger early this year, so be it. Forgiving the unforgivable Jew de mot, this was the esteemed Swiss-French composer Arthur Honegger.

And typically, Mr. Botstein was ready not only to share knowledge but to share the Grace Rainey stage. First with The Orchestra Now, and second, not in that order, with Dita Armory, Curator of the Met Museum Robert Lehman Collection, this season presenting the work of “Félix Vallotton: Painter of Disquiet.”

The endeavor was to explain the link between the painter and the composer, whose careers almost overlapped. And since I had never heard of painter Vallotton, it was a double education. As well as a chance to hear Honegger’s First Symphony.

Some of the links were obvious. Both painter and composer were Swiss, scions of food entrepreneurs (chocolate and coffee respectively). Both lived most of their lives among the great French avant-garde movements during the first half of the 20th Century. And both were ardent Leftists.

Vallotton’s woodcuts and oil-on-cardboard paintings illustrated the plight of the European underclass, his black-and-white work sometimes resembling that of George Grosz.

Nothing in Honegger’s music came near to his Communist membership. No marches, no Dessau-Brecht coruscating satire. One imagines that Honegger’s were zeitgeist allegiances like the American Leftist artists of the 30’s.

A. Honegger/Gabrielle Vallotton

After that, the links were less manifest. Vallotton never changed his politics, but, according to Ms. Amory, his styles evolved (or devolved) according to his discoveries. He painted marvelous less than realistic landscapes, he worked on portraits, he was part of the Symbolist movement, and when he discovered Japanese woodblocks in the early 1900’s, he pursued that with meticulous fervor.

While his name was unknown to me, I have every intention of visiting the Met–if only to see Vallotton’s and Picasso’s portraits of Gertrude Stein side by side.

Mr. Botstein did his usual job of explicating, contexting and giving non-technical analysis of Arthur Honegger, but the link with Vallotton was never made apparent. What was apparent–and what I had only suspected before–was Honegger’s commitment to his Classical forebears. I wouldn’t call him a neo-Classicist, for that would limit his sometimes mad humor (as in Saint Joan) or his pictorialism (Pacific 231). Rather, as the TŌN group later showed, this was a natural sense of balance, a seriousness unlike many of his French contemporaries.

Poulenc, Ibert, Auric, iridescent as they were, rarely had Honegger’s emotional brunt, his intensity in the oratorios or symphonies. Maestro Botstein explored, then, the influence of Beethoven, of Bach, of Dukas and above all Stravinsky. Which sounds like an eccentric buffet–but this is where Mr. Botstein made his mark.

With the First Symphony examples from TŌN, he showed just how Honegger worked with Classical, with Cubist, with light parody (the Dukas Sorcerer) and other emblems. What he didn’t mention was that Honegger wrote this work in his 40’s. (Unlike Brahms, he didn’t whine that Beethoven was breathing down his neck.)

After the intermission, Mr. Botstein conducted the whole work. TŌN is a young orchestra, and the two outer movements have a vivacity and a lovely soft ending. That long Adagio wasn’t quite as uplifting as the composer might have wanted, but was still interesting.

Not as interesting the two great oratorios, amongst the most powerful in the 20th Century. Yet Vallotton had become a figure to be reckoned with, Honegger’s underlying foundations were revealed. And that, for a Sunday afternoon, was sufficient.

Harry Rolnick

|