|

Back

Rhythms from the Founding Fathers New York

Behind the Door

09/17/2019 - & September 23, 26, 28*, 2019

Benjamin Yarmolinsky: The Constitution: A Secular Oratorio

Liz Lang, Michelle Trovato (Sopranos), Linda Collazo (Mezzo-soprano), Andrew Egbuchiem (Counter-tenor), Byron Singleton (Tenor), Roland Burks, Blake Burroughs (Bass-baritones)

Matthew Lobaugh (Piano), The Vertical Player Repertory Chorus, Peter Szep (Conductor)

Karni Dorell (Scenic design), Christopher Denver (Stage manager), Steve Witting (Director of productions), Judith Barnes, James Rutherford (Co-directors-Stage Directors), Vertical Player Repertory (Producers)

P. Szep, VPR Chorus and soloists (© Christine Walker)

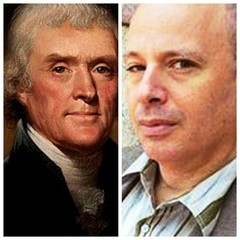

“Some men look at constitutions with sanctimonious reverence, and deem them like the ark of the covenant, too sacred to be touched. They ascribe to the men of the preceding age a wisdom more than human.”

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826)

To be candid, everything about The Constitution: A Secular Oratorio was wrong. To be equally candid, the entire piece was more stunning than I could have ever imagined.

The idea of composer Benjamin Yarmolinsky was to set the entire Constitution of the United States (including the signers and most of the Bill of Rights) to choral and solo music. Who in his/her right mind could set to music “No law varying the compensation for the services of the Senators... .etc” to a good tune.

Second, why on earth should one set to music a piece of parchment written two-and-a-half centuries ago which venerates slavery, male genders, property rights? Granted, one might as well blame Geographer Ptolemy for thinking the Earth was flat, but he is forgiven. So one must reluctantly approve of our National Anachronism.

Finally, Mr. Yarmolinsky–who has composed music to other national documents–never made an attempt to bring it into the musical 21st Century? Nationalism has nothing to do with it. Even Stravinsky set the National Anthem with a few dissonance (and almost landed in Boston prison)

Yet this oratorio was composed with harmonies which would have pleased that good old Handelian, Ben Franklin, while Jefferson might have allowed his cello for a basso continuo to the lively piano of Matthew Lobaugh.

Still, on the surface, we had a group of singers–wonderful singers with even eloquent soloists–who sung diatonic music resembling those abominable short-sleeved Christian singers in front of the American flag in the paranoid 1950’s. Or the Mormon Tabernacle Choir resounds with their tonic-dominant cadences today.

So what happened here? Before entering the tiny theater, one passes through crowds of people under the signs “We” and “The” and “People.”

Cute. But those doors remained open for the whole performance, so those on the outside could hear the choirs.

Not cute, but quite stunning and confident were Mr. Yarmolinsky’s settings themselves. After listening for a few minutes, one realizes this is not Randall Thomson jingoism, nor is it satire. Rather, it has the rhythm, the love of words which Virgil Thomson gave to Gertrude Stein. Granted, that was more solo than choral, yet one still had the feeling that Thomson avoided literal meanings to give it punch and vibration.

So we had a choral opening (repeated at the end) of the Preamble, followed by brilliant rhythmic lines to all those boring sections which were created by Jefferson, Madison, Monroe and the others from the Age of Enlightenment.

Very little in the Constitution itself was ideologically composed. (Though the audience applauded after Article I, Section 3,6-6–the Articles of Impeachment). And yes, when a solo was given for the “Slavery Allowed” Article, the chorus and soloists turned their backs. Otherwise, this was tuneful, perhaps old-fashioned but always terrific music which could have been enjoyed for the past two centuries.

One felt the Handel oratorio joy throughout, though a bit of Bach plagiarism was allowed when singing of High Crimes and Misdemeanors.

T. Jefferson/B. Yarmolinsky

The second half, the Bill of Rights, needed no apologies for bias. The Prohibition Amendment was doleful–and the repeal was delighted with dancing and near drunken merriment. After the clauses repealing slavery, the choir departed, and bass-baritone Roland Burks orated part of a speech by Frederick Douglass which was one of the most powerful I’ve ever heard.

Conductor Peter Szep took those long-dead lines from the Constitution and gave them both elation and ebullience. His 14-voiced choir with the nine soloists have sung it for several months now (this, alas, was the final performance,) and were on pitch, on tone. Most of all, in the tiny area where they sung and pranced between the rows of audience, they were not afraid to communicate with the audience. Eyes, smiles, waves seemed to say that “We the People” included even us.

The soloists were simply grand. Both sopranos happily went through their paces, while mezzo Linda Collazo has one of the most natural and lyrical voices I’ve heard in a long time. (She was equally dramatic, but could she summon up the passion of a Carmen?) All the others listed above, either in chorus, solo or ensemble (far too many numbers of enumerate), had the right idea.

And that apprehension–despite my skepticism after a lifetime studying Mencken and Zinn and despite the present political situation–that Mr. Yarmolinsky might have been flogging a dead horse was laid to rest.

Yes, it was the Constitution of the United States, but the composer’s obvious enjoyment in the composition, the brilliance in setting moribund texts to mirthful music, was a singular experience, not so much an homage to national rules as an appreciation of musical life, liberty and the pursuit of our happiness.

Harry Rolnick

|