|

Back

Two Shakespeares and an Idealized America New York

David Geffen Auditorium, Lincoln Center

09/18/2019 - & September 19, 20*, 21, 2019

Philip Glass: King Lear Overture

Samuel Barber: Knoxville: Summer of 1915, Opus 24

Sergei Prokofiev: Selections from Romeo and Juliet, Opus 64

Kelli O’Hara (Soprano)

New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Jaap van Zweden (Conductor)

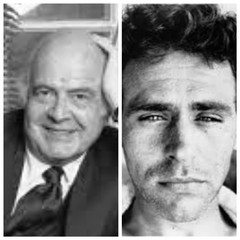

K. O’Hara, J. van Zweden (© Chris Lee)

“I’ve had little success in intellectual circles. I’m not talked about in the 'New York Review of Books,' and I was never part of the Stravinsky 'inner circle.' I can only say that I myself wrote always as I wished, without a tremendous desire to find the latest thing possible.”

Samuel Barber (1910-1981)

Jaap van Zweden opened his second New York Philharmonic season this week with a grand gesture: the world premiere of a new work by Philip Glass. The only problem being that Mr. Glass had given us the wrong title.

His King Lear Overture should have rightly (if awkwardly) been called Act Three Scene Three Overture. Mr. Glass never tackled King Lear. Rather, he tried (and came near to capturing) the famous “blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! Rage! Blow!” etc etc, words as Lear stands on the blasted heath ranting his fury against “ingrateful man.”

Yet even Hector Berlioz, whose Le Roi Lear overture is the most famed, knew that Lear was about Cordelia, about mercy and majesty and human tragedy as well as foul disillusionment. Mr. Glass, who had written music originally for the recent Broadway production, simply let himself go one-dimensionally wild.

Yes, it was a ten-minute symphonic tour de force. Arpeggios swirled, the orchestra dashed up and down, a few melodies blurted out and we lost. A Berlioz, with the same massive orchestral forces, gave us solos and tuttis, changed melodies and harmonies, allowed us into the romance as well as the delirium. One felt that King Lear was not an outcry, but a complete five-act drama, one of Shakespeare’s most varied, urgent, even mysterious tragedies. Philip Glass gave us pileups of orchestral consorts, juxtapositions of dissonance and consonance...

Yet it was without context, without personality. He could have called the piece Inferno or Karamazov or Juggernaut, and the effect would have been the same.

Mr. van Zweden conducted the New York Phil with force and–so far as one could tell amidst the roiling ensemble–with efficiency. Yet this was Glass the craftsman, not Glass the inspired. As if anybody could be more inspired than the original Lear itself.

One had no question about the NY Phil in its final suites from Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet. It was hardly in chronological order, sad to say, but the orchestra produced the quicksilver whispers of Juliet, the hard-hitting fights, the mournful strains at the tomb.

This was the second Shakespeare selection of the evening, but Prokofiev had paid attention to all the moods of this youthful work, and the diversity gave a vibrant moving picture, not the ten-minute snapshot of a drama.

S. Barber/J. Agee

What can one say about Knoxville Summer of 1915? The music to James Agee’s prose poem is widening illusionary ripple. First, the innocent idealization of a quiet Tennessee day and night 104 years ago. Then James Agee’s recollection of those guileless days told 20 years later, after America’s first international war, after an economic Depression.

(And a Depression captured by Agee in his Let Us Now Praise Famous Men with Walker Evan’s pictures as precursors to Robert Frank, who died this week.)

Then a recollection of Agee’s words by Samuel Barber in 1941, while the world was going to war.

And finally, a performance before a well-dressed affluent New York audience this week, an audience which probably visualized Agee’s gentle words as descriptions of country-hicks from faraway.

So, generations and geographies apart, a New York orchestra with a Dutch conductor and a crossover singer-actor attempted to put the Agee-Barber conception to life.

It did work. Barber’s conservative mien was ideal for Agee’s words. The latter was America’s first serious film critic, and his visions fit the Barber rhythms, the words, the Norman Rockwell pictures of rocking on the back porch, lying on the grass, the memories of a man looking back and a child experiencing the emotions of gladness and peace and comfort.

The music opening resembles those other American-evocative openings of Brooklyn-born Aaron Copland’s openings to Billy the Kid and Appalachian Spring, but Barber never departed from those lines.

Vocalist Kelli O’Hara never tried terribly hard for an operatic performance. This was Barber’s re-arrangement for chamber orchestra, so the light, almost emotionless lyricism of Ms. O’Hara let us enjoy the mood as much as the music.

Nothing more could be said. However Barber is evaluated today, Knoxville is perfect music for Agee’s perfect impressions. And at the end, one recalls that other poetry, this from D.H. Lawrence: “And I weep like a child for the past.”

Harry Rolnick

|