|

Back

Hail to Thee, Our Alma Mahler New York

Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium, Metropolitan Museum of Art

09/30/2018 -

Sight & Sound: “Mahler & The Feminine Ideal”:

Gustav Mahler: Kindertotenlieder

Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele: Artworks

Michael Anthony McGee (Baritone)

The Orchestra Now (TŌN), Leon Botstein (Conductor, Lecturer)

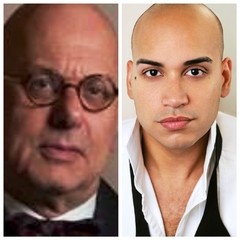

L. Botstein, M. A. McGee (© Courtesy of the Artists)

“Mahler was not a visual artist. He was an artist who transformed emotions.”

Leon Botstein, in remarks at the Metropolitan Museum concert

Not Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, Sartre or Heraclitus could solve this puzzle. On a crisp sunny autumn Sunday in New York, filled with pettable dogs and scampering squirrels, perambulators, babies, lovers and friends, why the hell would anybody want to slump into a museum seat in other to hear songs about dead children?

Well, I’d made the decision, and Leon Botstein’s words are always enlightening and the fourth song of Gustav Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder does indeed take us for a jaunt on the heights of the countryside...so...

To quote another philosopher, Ecclesiastes, the sun also rises. Which it would the next day. The music was this afternoon. And if Mr. Botstein’s “The Orchestra Now” did not produce the atmospheric emotions of Mahler’s quintet, baritone Michael Anthony McGee was a convincing and often beautiful baritone.

Mr. McGee’s performance was lyrically gorgeous, his voice an effortless instrument. Mahler himself regarded the voice as part of an orchestra, and Mr. McGee had an easy time of it, from the lowest tones to almost a falsetto when necessary.

That may not have been to everyone’s liking. After all, the Rückert poems–clearly enunciated though helped by the titles on the screen–are screams of understated agony, and while the poems were written in the early 1840’s, they possessed the repressed dream-images of Sigmund Freud. Nor was the music of death close to that of Shostakovich and Mussorgsky. These had a terror somewhere between Stephen King’s Pet Sematary and The Monkey’s Paw.

Little of this came out with Mr. McGee’s lilting baritone voice. One felt a pleasure in hearing him, but rarely was one moved emotionally.

Still, this was Mr. Botstein’s afternoon. His “Sight & Sound” talks are more than enlightening: they are radiant with information, opinion and–most vital of all–giving us listeners, amateurs and professionals, an original and compelling glimpse new artistic vistas.

I would hesitate using the word “polymath” to describe Mr. Botstein, since this summons up a kind of freakishness, knowledge for quiz shows. Mr. Botstein’s knowledge is extensive and eclectic, yet the fundamental aspects are the links between the most disparate elements.

This afternoon, he had the obvious sexual family links of 1900 artists in Vienna. Just about everybody married or had affairs with everybody else, and they all partook of Alma Mahler. More essential were his words about rule-breaking, about Freudian unconsciousness, and painting multi-dimensions in the works of Klimt and Schiele.

Part of G. Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze

The work above was displayed, but was hardly representative of the titled “Feminine Ideal”. Mr. Botstein gave this “ideal” as being dangerous and exotic, seductive and pure. And if this description also fit the ideal of Medieval Women, so be it.

One had to ask why, then, Mr. Botstein chose Mahler’s Songs on the Death of Children for his music. After going briefly through Mahler’s marriage (correctly giving scant mention about the death of Mahler’s own daughter four years after the cycle), he turned to the music itself.

These were the conductor’s halcyon moments. With excerpts by The Orchestra Now, he showed how each song had an evocative “hidden language”. It could hark back to Wagner’s Tristan or Schubert’s Death and the Maiden. He opined that the glockenspiel in the first and final song (with celesta) were the notations of children. And how the penultimate song was pure irony, Mr. McGee singing how mother and child were probably “taking a walk in the country.”

The results were not revelations in the religious sense. Rather, Mr. Botstein gradually disclosed truths which made some of us think, “Hey, I’ve listened to this piece countless times. What didn’t I think of that?”

The other result was coming home and listening first to the Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and then the Janet Baker Kindertotenlieder. Leon Bostein had turned on the floodlights, and we felt, more than ever, the glowing radiance of Mahler’s creations.

Harry Rolnick

|