|

Back

Portraits of the Artist’s Portraits New York

Flea Theater

05/15/2018 - & May 17, 19, 20, 2018

Artemisia: Light and Shadow

Francesco Cavalli, Barbara Strozzi (Music), Nahma Sandrow (Libretto)

Sara Chalfy (Artemisia)

Hideki Yamaya (Theorbo), Gwendolyn Toth (Music Director, Lute-harpsichord)

Paul Peers (Stage Director and Set Design), Chenault Spence (Lighting Design), Carol Sherry (Costume Design), Emily Clarkson (Projections)

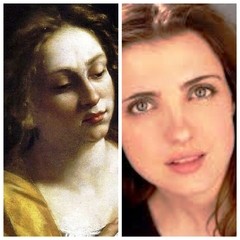

A. Gentileschi, self-portrait as Mary Magdeline/S. Chalfy

(© Sarachalfy.com)

One initially could classify the latest offering from Artek as a triptych. Except that the triptych assumes a religious allusion, and Artemisia: Light and Shadow is a charming, wicked, stunning and totally secular study of an early Baroque painter.

Instead, one must classify this hour-long study as an honor to the triumvirate Muses of painting, drama and music.

Entering the Flea Theater auditorium, one sees the stage divided into three, with drapes as a semi-division. On one side is a huge standing palette, upon which visuals of the stunning Artemisia Gentileschi paintings are shown, projected, given closeups when necessary. In the center sits the painter in a Cerulean-blue Baroque gown, sipping her chocolate. On the right is Music Director Genevieve Toth at the harpsichord, Hideki Yamaya tuning the theorbo.

The staging, the use of these three is as imaginative as the original Gentileschi paintings themselves. Yet nowhere near as original as the early Baroque painter, Artemisia Gentileschi.

Sara Chalfy enacts that painter in this one-woman hour-long show. Her story, partly true and partly the invention of librettist Nahma Sandrow, gives a three-dimensional portrait of the painter herself. She speaks of her father-teacher-artist, of her rape, her marriage, her children, her toughness (a letter telling a donor to give her the promised money). And above all, about her paintings.

Just as her father had been taught by Caravaggio, Artemisia’s figures were Biblical and ghastly, dark and light, bloody and passionate. Her own self-portraits, she admits, were not literally herself, but pictures to depict other feelings. Her success, she affirms, was because of her “wits...hands...self.”

Her rape at the age of 18 is, yes, a vicious torment, but it never stops her from continuing her life, her genius, her pictures.

That could have been enough. But Ms. Sandow and her colleagues offer as much imagination as the story itself. As Ms. Chalfy relates, for instance, her rape, she depicts it on a blood-red velvet rug, the wooden hands which serve as models, become the hands of the rapist in an astounding physical contortion.

But now, director Paul Peers, projectionist Emily Clarkson, and the two musicians frame the rape. The picture on the giant easel shows a Biblical portrait of an androgynous victim, with three menacing male figures behind the victim. Closeups of the eyes, the smirks, the hands complement the rape itself in the middle of the stage.

And on the right, the musicians play one of the strophic songs by another early Baroque master, Barbara Strozzi, sung by Ms. Chalfy herself.

It is an agonizing moment, yet only one of the moments entangling the three arts in production.

One must take a historical interlude here. Just as Caravaggio taught Artemisia’s father, and the daughter took over, so composer Barbara Strozzi was the product of an amazing Renaissance-Baroque generation.

Claudio Monteverdi’s prize student was Francesco Cavalli, and Cavalli taught Barbara Strozzi, whose success in her lifetime was great. In fact, Cavalli had written an opera called Artemisia, and though it was based on mythology, Cavalli certainly knew of the eponymous history of last night’s central figure.

B. Strozzi painted by Bernardo Strozzi/N. Sandrow

(© Courtesy of the artist)

Musically, both Cavalli and Strozzi are represented, their dramatic songs (by Cavalli) and stophic tales of torment, fate and the usual unrequited are sung from Strozzi’s songs and cantatas. Their purpose was twofold: to set the early Baroque musical background to the story, and to give emotional reflections of the painter’s own story.

Sara Chalfy of course dominates every moments here. Initially, one feels a lassitude, as she calmly turns to the audience and sings (what I believe) is the aria from Cavalli’s opera). Within a few minutes, one realizes that Ms. Sandrow’s libretto is only vaguely a timeline. Instead, with the paintings and music together, one begins to feel a full portrait of a highly complex individual.

And a highly confident individual. Within her times, rape was hardly uncommon. Yet within Artemisia’s artistic soul, her rape was never forgotten. She was never prevented from pursuing her well-documented career, but her paintings–gruesome, aflame, emotional, arousing–could well have been a catalyst for her creations. (I would say “unconscious”, but no words like that existed in the early 17th Century.)

Ms. Chalfy was unlike the paintings of Artemisia. They are fearsome creations typical of the post-Caravaggio era. Ms. Chalfy’s character is multi-dimensional, as student victim, artist, proud mother and businesslady. And one relates to such a character immediately.

Her voice for this so difficult music is usually up to the test. Perhaps she strains too much at the upper regions, but basically her range and her understandings are up to the task. And after all, Mr. Chalfy is playing a character, not giving a recital.

The result is more than memorable. Walking back from the Flea Theater, way down on Broadway, one could forget the storms and the distance, and recall this meeting of the arts. For it was produced with the single most essential strength of any artist from any era: unerring, and frequently resplendent vision.

Harry Rolnick

|