|

Back

Multi-Widmann Mementoes New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

04/13/2018 - & March 29, 30, 31, April 3, 2018 (Boston)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Symphony No. 23 in D Major, K. 162b [181]

Jörg Widmann: Partita, Five Reminiscences for Orchestra (New York Premiere)

Richard Strauss: Don Quixote, Fantastic Variations on a Theme of Knightly Character, Opus 35

Yo-Yo Ma (Cello), Steven Ansell (Viola)

Boston Symphony Orchestra, Andris Nelsons (Conductor)

Y.-Y. Ma/A. Nelsons

“In the course of years, Sancho Panza fed him a great number of romances and adventure in the evening and night hours, diverting his demon, which he called Don Quixote. This demon set out, uninhibited, on the maddest exploits, yet harming nobody. A free man, Sancho Panza followed this demon on his crusades, and had a great and edifying entertainment to the end of his days.”

Franz Kafka, The Truth About Sancho Panza

Miguel de Cervantes’ cosmic duo appeared after the intermission of this third concert by the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The evening opened with another duo: an homage to simplicity and a challenge to acquired knowledge.

The simple was a falsely-named 23rd “Symphony” by Mozart. It was unknown to most of the audience (including this writer), hardly qualified even as an early Haydn-style symphony at all. Instead, it was a three-movement Italian-style overture, without a break, since Mozart wrote an Attaca between the movements.

Conductor Andris Nelsons gave the antiphonal fanfares for trumpets and winds all the zest and energy necessary, heralding what could have been a minor Mozart Singspiel. The real hero of the occasion–as in the later Strauss solos–was First Oboe John Ferillo, who led the second movement with charm, color and fluid beauty.

The beguiling Mozart led to the 40-minute Partita by Jörg Widmann, a work which could only be titled a musique á clefs. The actual music comes later. First come the “keys”. Initially the key of “B minor” in honor of Bach’s Mass. Next, since Mr. Nelson’s is now the conductor of both the Boston and Leipzig orchestras (which commissioned the piece), all the composers quoted had a connection with Leipzig.

Now the quotes. Quite a few from Bach (including the “Brandenburgs”), some

Wagner motifs in the outer movements, a sort-of Brahms Fourth Symphony chaconne (though this one is an 11-note rising scale), along with bits of Mahler. And a jazzy-ish madcap Divertimento which seems to hark to Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra.

What did this add up to? Difficult to say. Mr. Widmann is an amazing orchestrator, he didn’t use tricks, but made these quotes jolt and surprise. He could be almost anarchic (as in the Divertimento) or flourishing with blazoning trumpets and crystalline celesta (in the short Gigue after a long doleful Grave.)

The clarinetist-composer gave homage literally to Mendelssohn’s Clarinet Sonata with a second movement that was purely 1824-ish. And his Sarabande was a light, never funereal piece of old dance music. Mr. Nelsons conducted it with a light hand, tying together solemnity and anarchy.

The result was clever, cunning, fascinating, rambunctious and...well more than a little ostentatious. Then again, the piece had been commissioned to commemorate the alliance of two orchestras, so why not offer the composer’s cerebral celebration?

If ya got the stuff (as Widmann does), ya might as well flaunt it.

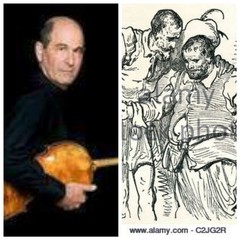

S. Ansell/Gustave Dorés D.Quixote and S. Panza (© Courtesy of the Artist)

Mr. Widmann’s piece demanded, even during its ersatz-jocular Divertimento, utmost attention. For the second half, Richard Strauss’s Don Quixote, we only needed to follow the leaders, take part in the adventures and enjoy a musical homage to this most profound, sympathetic and human looks at that creature Man(un)kind.

And oh, how Yo-Yo Ma and violist Stephen Ansell steeped themselves into those adventures. Mr. Ma does play to the crowds, he comes on stage waving, smiling, hugging his fellow musicians. Mr. Ansell as part of the orchestra (as Strauss had wished the cellist to be) was more conservative. But they both played Quixote and Panza with the utmost pleasure.

Andris Nelsons was not afraid to alter the moods, almost with exaggeration. Not to a disconcerting tempo, but making the slow introduction very slow, and the meandering talks in Variation III, indeed weaving and wandering, as would be the case at they walked through the Iberian countryside. When the Boston Phil built up their harmonies in the final sections, his was an architectural erection of color.

And how Mr. Ma took advantage of this! His cello was so romantic when chatting with the mythical Dulcima, he played hard against the strings in the fight with the windmills. But at the end, with the death of the Don, with his friend Sancho Panza, his sane soulmate at his side, the cello played with an aching, a desolation, yet with the satisfaction of a mad life well lived.

The cellist has played this countless times, and I last heard him at Tanglewood. But Yo-Yo Ma is a student of literature as well as music, and his understanding of Cervantes has now become deeper than that of Strauss.

On the other hand, listening to Jordi Savall’s authentic music from the time of Cervantes, I realized that this great story-teller might have heard this performance of Strauss with the same enjoyment as he had in creating those so so compassionate eternal figures.

Harry Rolnick

|