|

Back

Creating Schubert’s Un-World New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium Carnegie Hall

03/02/2018 -

Franz Schubert: Piano Sonatas in B Major, D. 575, in A Minor, D. 845, & in D Major, D. 850

Mitsuko Uchida (Pianist)

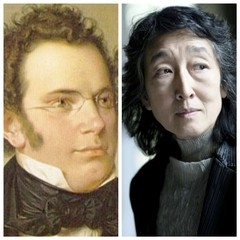

F. Schubert/M. Uchida (© Decca/Justin Pumfrey)

Mitsuko Uchida is not a pianist who learns the classics, learns the moderns, adds some Baroque and gives a recital. Unlike any pianist I know, she sinks herself deeply into the archives, the urtexts, the music, the lives and the inner feelings of a single composer, preparing to show their entire repertory.

Thus, her two recitals of Schubert this year–finishing with two more Schubert recitals in 2019–bear a Papal imprimatur.

Not that all could or should “agree” with every note she plays. But when she surveyed last three sonatas (minus the B Flat) on Monday, one felt that she had reached into the dark psyche of Schubert as much as possible. And playing three early– and middle-period sonatas last night, one had a different feeling.

To be specific, for the unworldly endlessly inspired Schubert, it was the feeling of immortality. Beethoven might have spent his life arguing and growling with publishers, agents, relatives. From last night, one feels that Schubert’s very joy in being would be equivalent to that of George Gershwin, another genius who died far far too early. That when Schubert or Gershwin would go to a gathering with a piano, they would sit down, improvise–and never leave the piano-seat.

Certainly one felt that in the earliest published B Major Sonata, where the 20-year-old felt that sense of joy, real joy. As did Ms. Uchida. Schubert was “classical”, but had he known of Palestrina, he would have reveled in through-composed music, where he wouldn’t worry about form. Ms. Uchida started with a jumpy opening theme and sailed through the different melodies with the spirit of youth itself. The tempos changed with the tunes, so by the time she came to the recapitulation, the temperate finale was like the end of a race well run.

The Andante enjoyed equal contrasts, and Ms. Uchida never hesitated in bringing out the glorious left-hand theme. After the scherzo, she gave us an exquisite finale, one filled with a series of ravishing melodies.

This was the sonata of an everlasting youth. The following two works, written just three years before the composer’s death, seemed to have inklings, scintillas of darkness. I doubt if Schubert had yet contracted the syphilis which would destroy him. Perhaps this naive young man realized that his success in Vienna was not a certainty, that the flash and filigree of his songs might have precluded public achievement, that he wasn’t born for the harsh musical politics of that wicked Hapsburg town.

Ms. Uchida might have realized that as well. The first movement of the A Minor Sonata had a decided weltschmerz. He could never summon up the fierce anger of a Beethoven, nor did Ms. Uchida try that. Instead, she hustled along with the angry martial theme. Did that playing with a vengeance upset the balance of the wonderful opening melody? Perhaps, but of no matter. The second movement was equally schizophrenic, and I’ve always regretted that the second theme is always taken so quickly. Nonetheless, Ms. Uchida played the whole work, with its quirky finale with her assurance.

The final “Gastein” Sonata (named for the rural section where Schubert wrote the D Major Sonata) was the longest, the most technically difficult and again, super-tricky to go through.

The infinite technical demands meant nothing to Ms. Uchida. On the other hand, I realized that one never thinks about her digital power. Just as one shrinks from those sexist comments that she is a “fastidious” or “elegant” pianist, equally one never thinks of her as a technical dynamo. She could be all three at the right times, but her personality is to bring a unity to whatever she plays.

The “Gastein” was reportedly Gustav Mahler’s favorite, and it was certainly the closest to nature. Not that Schubert musically ruminated about flora and fauna. Instead, Ms Uchida had him running through the woods (probably with one hand holding onto his glasses), she had him singing through the second movement with some glorious lieder. If the horn call was bit strident, amen for all that. One didn’t ask for the ideal forest.

The finale is rarely successful. The tick-tock theme sounds like the accompanying figure for a metronome, and Ms. Uchida couldn’t quite rid the figures of their affectedness. The rest of this quirky finale was dazzling, as was the completeness from the rest of the concert.

No, it didn’t have the dark poetic allusions of the first recital. But it did have a vivacity, a few happily jolting measures, and always Ms. Uchida’s confidence.

Where the first recital ended with a wisp of Schoenberg, here she played a the sarabande from a Bach French Suite. As if to summon us back next year on April 30 and May 4 for another world of the unworldly composer.

Harry Rolnick

|