|

Back

Luigi Nono and the Terrors of the World New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

03/01/2018 -

Luigi Nono: Intolleranza 1960

Daniel Weeks (Tenor, “An Emigrant”), Serena Benedetti (Soprano, “His companion”), Hai-Ting Chinn (Mezzo-soprano, “A Woman”), Matthew Worth (Baritone, “An Algerian”), Carsten Wittmoser (Bass-Baritone, “A Torture Victim”), Elizabeth Smith (Soprano “Solo”), Gregory Purnhagen, Blake Burroughs, Steven Moore, Michael Riley (Policemen), Mark Rehnstrom (Voice of Henri Alleg), Alex Guerrero (Voice of Jean-Paul Sartre), Thomas McCargar (Speaker)

Bard Festival Chorale, James Bagwell (Director), American Symphony Orchestra, Leon Botstein (Conductor/Musical Director)

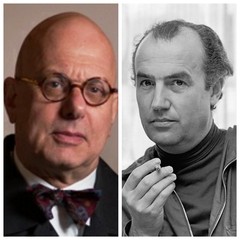

L. Botstein/L. Nono (© Open Societies Foundation/Wikipedia Commons)

“The object of terrorism is terrorism. The object of oppression is oppression. The object of torture is torture. The object of murder is murder. The object of power is power. Now do you begin to understand me?”

George Orwell, from 1984

“Intolleranza 1960 suggests that none of us can assume we are immune to the character of the public life we not only live in, but passively and actively helped create.”

Leon Botstein, from Program Notes to Intolleranza 1960

Last night, Leon Botstein and choral director James Bagwell created the first landmark in 2018’s musical history. Luigi Nono’s Intolleranza 1960 is not only one of the most blatantly political operas of all time, but its production here, and Mr. Botstein’s written notes were both stunning.

True, opera from the start was political. Both Figaro and man Verdi operas were barely masked satires against the State. Tosca was unashamedly a screed against the Church, as Berg’s Wozzeck spoke about man’s inhumanity to man, while Martinů’s Comedy on the Bridge was a commentary on the repugnancy of State borders. And while America’s 20th Century composers were virtually all Limousine Liberals, Marc Blitzstein did write the brashly political Cradle Will Rock.

Luigi Nono, a product of Italy’s post-Fascist and totally polarized society, was a Communist from beginning to end. His Intolleranza 1960 was more than a nationalistic screed. The libretto, by Angelo Maria Ripellino dealt with issues which are all too prominent today–in two-thirds of the world’s countries, including our own. Immigration, torture, unlawful interrogation–and most of all, intolerance, the human inhumanity to other humans.

Into this, both librettist and composer injected the words of famed figures including Jean-Paul Sartre. Note that they did not include ideological figures from ther own Communist Party. Nono and Ripellino were, even for radicals, radical artists, eschewing the Soviet Union for the universality of the world itself.

That, in Stalinist terms, would be almost Trotskyite! But Nono had the confidence, the compassion, the sympathy and the honor to pull that off.

Not, exactly in proletariat terms. He was no Kurt Weill. He was a Darmstadt composer through and through. And if he didn’t work with a tone-row (Nono revered his father-in-law Arnold Schoenberg), he worked outside of scales or keys.

Like Pierrot lunaire, this opera’s music worked with the emotions themselves.

Which brings us to last night’s performance. First, one longed for some kind of stage performance. Intolleranza was originally staged for simultaneous actions, bringing together both torture and passion, both the hideousness of the State to the possibilities of companionship.

H.-T. Chinn/J. Bagwell (© Katherine Milford/ASO/Bard.edu)

But if we didn’t have that, we had the Bard Festival Chorale, directed by James Bagwell. Whether screaming out the Chorus of the Tortured or the atonal last Brecht-written hopeful chorus, or giving vent to megaphoned commentary, this was incredibly difficult. Loud choruses in minor-second harmonies were sung out with seemingly not a single problem. The choruses were invariably loud, urgent, discordant. Yet the effects were uniformly effective.

Granted, not always as effective as they could be. So homogenous were the emotions demanded in their multiform roles, one felt little differentiation. Rather, one heard that compulsion which urged on the entire opera.

Then we had Mr. Botstein’s American Symphony Orchestra, which seemed to be right on that same compulsive pitch. I have not seen the score, yet I felt that the trumpets at their highest pitch, the scattered woodwinds and percussion for the sounds of torture (Nono eschewed the easier way of more bawling brass), and the string settings gave that same background to the singing.

No voices were natural. Tenor Daniel Weeks spent most of the opera in a near-falsetto for “The Emigrant”, yet again this was a necessity for the part. He had to go from the exploited mine-worker to the victim of torture as he was accidentally found in a protest meeting.

(I am certain that librettist Ripellino got that idea from the same scene in Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights, which even today is a harsh picture of life the common man.)

Mr. Weeks, who did attempt acting in his front-row appearance, was fine in his role. But musically the malicious ex-lover and then torturer, Hai-Ting Chinn was far and away musically the most faithful to the Nono credo. In every score I have read of his, each note has the most intricate directions. Ms. Chinn shaped every single note into diminuendos, into mini-crescendos. Whether at the top or bottom of the mezzo scale, she never simply sung, she made each note a story. I was stunned not so much by her voice, as her subtlety, her dramatic power within the whirlwind of the opera itself.

The audience favorite was Serena Benedetti, for good reason, as she was the archetypal 21st Century avant-garde soprano. Her whisks up and down the scale, or giving vent to the highest notes, was more than impressive.

Smaller roles–torture victim Carsten Wittmoser and the so sympathetic Algerian companion Matthew Worth–were both fine. The policemen were vicious and the voices from the chorus quoting icons of the time through megaphones were equally powerful.

Happily, Mr. Botstein never took an intermission. In fact, any break between the horrors of the first half and the slower, more human second half would have been a tragic break.

(Besides giving some cowards in the audience the chance to escape music which they couldn’t bear.)

Yet in this second half Nono and Ripellino inserted a long chorus which was not only revised for the 1970 Intolleranza, but could be revised for a 2018 production. This was a litany of absurdities.

After a repetition of “censure!”, and the multi-lingual words which classify any closed society–proibito-défendu, verboten-forbidden–the chorus launches into the inanities of “Dummyland” (that was the original English). From a-bombs exploding in Dummyland to elephants rampaging in Luang Prabang, to “Atomic Clouds Amass over Our Southern Region”, we had a list of the Cold War horrors in 1960.

And oh, should City Center Opera ever decide to stage this opera, I would be thrilled to write another codex of horrors, horrors of our own time. Horrors which transcended Stephen Colbert or Saturday Night Live or the multitudinous media geniuses who in Mr. Botstein’s words, “passively and actively helped create” the chaos of today’s America.

I confess to not resisting these entertainment titans. At the same time, witnessing the 90 minute tension, repulsion, ugliness, faint specks of light, and all too contemporary inanities of Luigi Nono’s azione scenica–his “stage-action”–this writer knows that we Americans are far too deficient in the fears and loathings in 2018.

And yes, we need a staged performance, we need that updating of the 1960 Intolleranza. Mr. Botstein, though, has offered more than a replacement. Like Theodor Adorno’s declaration, that “suffering has as much right to expression as a tortured man has to scream,” he has given us the political revelations of Luigi Nono and, with Wozzeck, the most meaningful musical drama of the 20th Century.

Harry Rolnick

|