|

Back

Words Into Music and Back Again New York

Hudson Hall, Hudson Opera House, Hudson, New York

11/11/2017 - & November 12, 15, 18, 2017

Virgil Thomson: The Mother of Us All

Michaela Martens (Susan B. Anthony), Nancy Allen Lundy (Gertrude Stein), Teresa Bucholz (Anne), Kent Smith (Virgil Thomson), Robert Osborne (Daniel Webster), Dominic Armstrong (Jo the Loiterer), Tea Boriss (Chris the Citizen), Ella Loudon (Indiana Elliot), Marie Mascari (Angel More), Dylan Widjiono (Indiana Elliot’s brother), Brad Lohrenz (Anthony Comstock), Marc Molomot (John Adams), Christopher Johnstone (Thaddeus Stevens), Amanda Boyd (Constance Fletcher), Ngonda Badila aka Lady Moon (Isabel Wentworth), Wheelock Whitney (Gloster Heming), Matthew Deming (Anna Hope), Libby Sokolowski (Lillian Russell), Veronica Forman (Jenny Reefer), Charles Perry Sprawls (Ulysses S. Grant), Ryan Tracy (Donald Gallup), Phil Kline (Andrew Johnson)

Elena Batt, Kam Bellamy, Anneice Cousin, Margot Kirsis, Michael O’gara, Parker Shipp, John Van Ness Philip (chorus), Stuart Quimby (flute), Louis Bonifati (clarinet), Christopher Watford (bassoon), Stephanie Hollander (French horn), Todd Dubrey, Allyson Keyser (trumpets), Mike Benedict (percussion), Nuiko Wadden (harp), Tony Kieraldo (Music Director)

R.B. Schlather (Stage Director), Lighting Designer (JAX Messenger), Marsha Ginsberg (Set and Costume Designer)

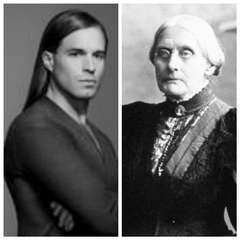

M. Martens, T. Buchholz (© Tobin del Cuore)

“The principle of self-government cannot be violated with impunity. The individual's right to it is sacred–regardless of class, caste, race, color, sex or any other accident or incident of birth.”

Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906)

She was a great lady, far far ahead of her times, not only a suffragette, but a fighter for all those considered dross during America’s so-called Gilded Age. And while Susan B. Anthony’s life overlapped with Gertrude Stein (when she died, Stein was 31), they hopefully will live forever in The Mother of Us All.

This was Gertrude Stein’s very last work, and composer Virgil Thomson always regretted that she didn’t live to see it. But Stein was a creator of words, not drama or opera, and it took Thomson’s genius to make this one of the very great American operas.

Or it should have been great. Something was elusive, even wrong here. That comes later.

The production yesterday afternoon in the historic old whaling town of Hudson, New York was one indication of the greatness of America. The voices of these two-dozen singers and nine instrumentalists (Thomson’s original orchestration was decimated) were more glorious than the other. I assume that each of the singers were from Hudson or its environs in this gorgeous section of New York State. They were listed in the program notes as being bartenders or social workers, art dealers, event planners, high fashion sales associates or ministers. Yet predominating were music teachers, actors, singers and voice teachers.

And oh, how it showed. And oh, what a difficult chore they had in making their voices known. For while The Mother Of Us All was far more straightforward, more human than Thomson/Stein’s collaboration, Four Saints in Three Acts, the straightforward structure was belied, or perhaps glorified by Ms. Stein’s brilliant convolution of words.

On the one hand, Mother was easy. Supposedly–and this was difficult to ascertain yesterday–it begins in Susan B. Anthony’s home, goes onto a debate with Daniel Webster, continues with two strange love affairs–John Adams and Constance Fletcher with the more fascinating fictional Indiana Elliot and Joe the Loiterer. And then goes onto more political debates and a few scenes where she is successful, and her statue is unveiled.

Contrast this with Virgil Thomson’s own explanation: “The opera is a memory-book of Victorian play-games and passions , with its gospel hymns and cocky marches, its sentimental ballads, waltzes…a souvenir or all those sounds and tunes that were once the music of rural America.”

Mr. Thomson, a creature of rural Missouri, knew these tunes, and how the citizens of Hudson, New York intoned them. One cannot praise enough the group ensemble, directed by Music Director Tony Kieraldo. For her few real extended arias, Michaela Martins, petite, maternal, dressed in a man’s suit, showed an operatic instinct. The Junoesque Ella Louden and her (sometimes) bare-chested fiancé Dominic Armstrong, gave marvelous performances. Robert Osborne as Daniel Webster, was eloquent in his prejudice.

This story cannot give enough credit to every one of the cast members above. For this is above all an ensemble piece, and the ensemble here, including choruses and soloists, dances and ranting, were beyond criticism.

One has equal plaudits for the orchestra, despite the lack of strings. (The original work introduces Susan B. Anthony with trumpets and strings, almost spiritual moments.) The march tempos, the rhythms, even the dances, were sharp to the point (and French horn-player Stephanie Hollander was almost perfect in a challenging part).

R. B. Schlather/Susan B. Anthony (© Hudson Hall, Hudson Opera House)

Yet something went wrong here. It wasn’t that the costumes of the cast were so off-putting. Some wore street clothes, some, like ‘Lillian Russell’ looked their parts, another, ‘Daniel Webster’ wore a Disney Mickey Mouse shirt. So the visual effect was blurred. Aurally Hudson Hall is not ideal for vocalizations, and the slight echo made many of the words foggy.

More important was the original concept created by director R. B. Schlather, a man esteemed in New York, a most innovative soul in the theatrical community. His stage was the bare rather ugly main hall of Hudson Hall, a mammoth space (I estimated it to be around 900 square feet), with a prominent stage. Hardly the easiest space in which to work. Mr. Schlather, though, opting to make full use of every inch of that space, created not a focus on Susan B. Anthony, her enemies and her admirers, but a focus on...well, no focus at all.

The audience sat in rows on each side of the Hall (including the stage), others sat in the middle of the Hall. Into their midst came the two-dozen performers. As well as the conductor. They sat on cheap tables, climbed on the stage, sat behind the audience, sang from the balconies, made their dramatic statements from every part of this area. Without lighting changes, without differentiation. The second act, Susan B. Anthony’s triumph had a weary sameness, as the cast walked slowly and more slowly round and round the entire Hall, up on the stage and down again.

Perhaps in Four Saints in Three Acts, or in Cirque du Soleil, this might have worked. But the original score of The Mother of Us All has distinct stage directions, and a distinct confluence on the eponymous heroine of the opera. Yet all was spaced out across the vast environs.

I pointedly avoided the director’s interviews, feeling that such a transparent story could stand on his own. And I have little doubt that Mr. Schlather had his reasons for spacing out his ensemble, of giving distances between the characters (a few times, like the Webster-Anthony debate, were held in the center, and were quite effective).

But one cannot forgive the staging of Susan B. Anthony’s valediction at the end–“Life is strife, I was martyr all my life not to what I won but to what was done.”

This was equally the valdediction of Gertrude Stein. As well as the essence of Virgil Thomson’s marvelous ear fiendishly clever melodies, for nuance and eloquent inflection.

Thus, Ms. Martens seated, barely seen in the middle of the Hall, was a downer, a lack of triumph. Corny as it might seem to Mr. Schlather, she needed a center, she needed a curtain or lighting to slowly come down on Mr. Thomson’s triumphant C Major chord.

That said, The Mother of Us All is a musical and vocal masterpiece by any standards. Both Stein and Thomson focused on a true unsullied heroine in American history, and the singers, one and all, had that eloquent focus in their voices. If only they had brought their ensemble togetherness into some kind old-fashioned theatrical physical togetherness, this wondrous opera could have been, instead of a respectful performance, an emotionally moving experience.

Harry Rolnick

|