|

Back

The Cymbal-ic Symphony New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

01/27/2017 - January 29-29, 2017

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante for violin and viola, K. 364

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 7 in E Major

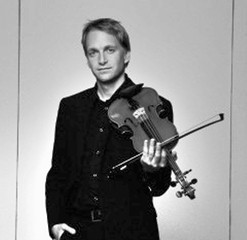

Wolfram Brandl (Violin), Yula Deyneka (Violin)

Staatskapelle Berlin, Daniel Barenboim (Music Director, Conductor)

W. Brandl (© Courtesy of the Artist)

“God has chosen me from thousands and given me, of all people, this talent. It is to Him that I must give account.”

Anton Bruckner

Well, God gave him the genius, but conductors like Daniel Barenboim are delegated to bring God’s notes down to earth. Which is exactly what the Music Director of the Staatskapelle Berlin has been doing this past week, with nine of Bruckner’s 11 symphonies. (Number 0 and Number 00 were not played.)

One can feel a bit OB’d–over-Brucknered–before leaving for Carnegie Hall. But once those low strings begin to hum, and the horns and trumpets and–in this case–four Wagner Tubas–begin to play, one forgets hearing the same composer every night. It is always an ecstatic experience.

Some of us would like the voyage to start immediately, but the conductor makes us wait, with a Mozart concerto. That is far far more than a painless experience. The conductor is a splendid pianist who never makes allowances for 18th Century reverbs, and he plays and conducts with great élan.

Last night, the piano gave way to the First Chair violin and viola of the Staatskapelle Berlin, who–with a few minor faults–acquitted themselves well. The Sinfonia Concertante is a joyous piece, more akin to Bach’s Double Violin Concerto, which Mozart had never heard. But the composer, was totally Italianate here, and Messrs Wolfram Brandl and Yula Deyneka played with unceasing energy, as well as an appreciation for each other’s talents.

Y. Deneyka (© Mariinsky)

There were mistakes aplenty here, alas. Though not enough to make any save the purist tremble with anger. The Staatskapelle was a bit blurry at the introduction, though the soloists came in with resonant (if not very subtle) phrasing. And if some of the tones of the second and third movements were a bit off, one could excuse it by saying the vivacity and spontaneity was preferable to perfection.

Perhaps in this case, perfection might have been dull. What we had a most charming and elegant work, and these two–who, after all, are ensemble performers rather than soloists–simply enjoyed their own performances. So who were we to question them?

As for Bruckner’s Seventh, Mr. Barenboim knew that if Mozart was a painting, Bruckner is architecture. Those blocks must be placed one on each other with the greatest care, lest the whole edifice falls down.

That incipient downfall never occurred. The opening seemed a bit slow, but never hesitant. And it gave scope for the grand openings, the fierce chorales and fanfares. As for the Adagio, one waited for the one cymbal crash. The story is too complicated, but nobody knows whether Bruckner wanted that cymbal to come in on the climax or not.

Barenboim did know, and the percussionist made the most of it. Holding the cymbals for a few minutes, crashing them on cue, then holding them for another minute (were the vibrations too hot?). As for the rest, the Wagner tubas did their part in honor of the later Richard. Perhaps, as the writer of so much religious music, Bruckner was punning away on Tuba mirum spargens sonum from the Requiem Mass.

The Seventh is the most “popular” of the symphonies, much due to that crackling scherzo, with some beautiful trumpet solos. To his credit, Mr. Barenboim started the great finale with a tenuous feeling, allowing the climaxes to evolve into the cathedral-like sounds so essential.

At one point, Ms. Barenboim held the fermata for so long–I would say close to 30 seconds–that I expected somebody in the full house to start applauding. They didn’t. Mr. Barenboim held our attention, and the attention of the listeners, who must have departed with both exaltation and elation.

Harry Rolnick

|