|

Back

The Orchestra, the Piano, and the Vocal Gloria New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

01/20/2017 - & January 6, 2017 (Paris)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 20, K. 466

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 2 in C Minor (1877, Nowak edition as revised by Bornhöft and Carragan)

Staatskapelle Berlin, Daniel Barenboim (Music Director, Pianist, Conductor)

A. Bruckner (© Lubiana.org)

“If philosophy can be defined at all, it is an effort to express things one cannot speak about.”

Theodor Adorno (1903-1969)

Daniel Barenboim is an artist, not a philosopher like Adorno. But in an enlightening interview about Anton Bruckner in this month’s Carnegie Hall Playbill, he almost repeats the words of Adorno:

“If music is an expression of what can be expressed that cannot be expressed in any other way, then Bruckner is of extreme importance.”

As Mr. Barenboim himself is of extreme importance in clarifying the Bruckner musical thoughts. Obviously in the age of television satires like Jude Law’s The Young Pope, Bruckner’s cathedral-sized Catholic belief may not strike too many chords. But like that other believer in the Church, Olivier Messiaen, the music resonates in the innermost parts of our soul and body. The Wine and the Bread are secondary to the emotions and the aspirations.

Daniel Barenboim conducts the music as it is written, in the basically uncut 1877 version. (I think he missed the trio repeat of the Scherzo). With the Second Symphony, performed last night with his Staatskapelle Berlin, Mr. Barenboim didn’t have to “reach” for emotions, as he did in the First Symphony the previous night. From those first tremolos, Bruckner had taken a basic classical musical form and–like the Church Eucharist–transubstantiated it into a monument.

Whether sacred or secular–and Mr. Barenboim’s strict discipline with his orchestra makes it lean to the temporal side–this Second was like a John the Baptist to the future symphonies. Trying to please the Austrian critics, he gave a one-hour “classical” symphony, complete with pauses to show where the themes, developments etc started. (It was ridiculed as “the Pause Symphony”) Yet so inspired was Bruckner, that one could overlook the orthodox structure to hear those splendid chorales and equally splendid “tunes” in the first movement.

Mr. Barenboim started the work with energy and never let go. One always wonders how conductors will handle the shlocky second theme, but the conductor never let it bother him. This was not Bruckner smelling the roses, this was Bruckner embellishing his grand beliefs with decorative icons, religious pictures.

Nothing was exaggerated here, the strings and those wonderful horns expressed the notes,especially the solo horn against pizzicato strings, and that was sufficient.

The Andante was not yet the famed Adagios of the later symphonies. But the lovely theme was brought back with the most elegant of counterpointed improvements. And the Scherzo was, again, a conservative, un-rustic cry of joy.

As for the finale, let us praise the Staatskapelle Berlin soloists as much as Mr. Barenboim. The horns, yes, but the brilliant difficult timpani, the ensemble of winds and brass, and of course the string consort. Bruckner’s chorale, his crescendo, his reverberating Gloria can sing for itself. With this orchestra, the singing became as rapturous and as vocal as one of Bruckner’s own splendid Catholic Masses.

Harry Rolnick

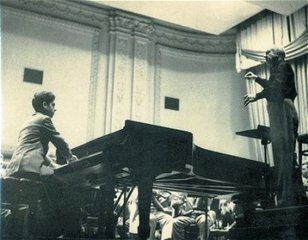

D. Barenboim, L. Stokowski (© DanielBarenboim.com)

As this rare picture of a rehearsal shows, on January 20,1957, a 14 year old pianist appeared on the stage of Carnegie Hall in company of Leopold Stokowski who conducted the Symphony of the Air. Last night, the 74-year-old pianist showed none of diminished capacities or loss of energy when he played solo part in the Mozart Piano Concerto No. 20 and then conducted the second of Bruckner symphonies in his historical cycle of performing all symphonies consecutively during nine evenings.

The Concerto is without a doubt the most famous of the 27, and that fame dates from the Beethoven’s time, as it was his favorite and for which he left two cadenzas: in the first and last movements. For these performances, Maestro Barenboim chose to perform only first of Beethoven dramatic cadenzas: the one just before the coda in the final Allegro assai. It was brooding enough, far from being as convincing as the one we often hear and unknown to me.

If the beginning of that Romantic concerto is tempestuous and agitated, Barenboim seemed to find in it a menace: by separating the syncopated notes in strings he created a strange atmosphere with threatening, ominous, rumbling surges in the lower strings. Even today, when we seems to know every note of the work, it still makes a powerful impression as if a deleted scene from his Don Giovanni. But I was impressed also by the shadings of piano and pianissimo rarely so finely executed. What also surprised was the reentering of the recapitulation section: normally the piano which brings it forth makes a little diminuendo: here the pianists made a point to forcefully announce the change of scene. The piano cadenza was dramatic, stormy and operatically passionate–as it should be.

Our artist took the middle Romance - another rare tempo indication in Mozart works - at surprisingly quick pace, akin to perhaps Andante con moto but it made musical sense. His solo cantilena lines again sung with a pristine serenity and when the clouds gathered in the middle part, the contrast was still quite pronounced. Here the composer gives pianist some extra exercises in hand-crossing. (I always wonder how the pianists with a waist-line “above normal” can negotiate those passages!)

The stormy frightening finale didn’t smile in that interpretation even at the end, when the key changes to major. It was still brisk, very impatient, very far from the merriment we usually hear during those last moments of the score. Barenboim generally displayed the similar qualities I described in my previous review: beautiful musicianship, great concept of the work and a bit of rhythmic unsteadiness that often mars his execution.

A friend asked me during the intermission if, like him, I believe that has he used another conductor and concentrated only on solo part, those pulse-controlling problems would disappear: I responded that if anyone can both conduct and play the piano part, it is Barenboim. With him I think it is the God-given ease of playing piano that sometimes causes the problems.

Roman Markowicz

|