|

Back

Alan The Brass-Kisser New York

David Geffen Hall, Lincoln Center

05/26/2016 - & May 27, 28, 2016

Sir Edward Elgar: Introduction and Allegro for Strings, Opus 47

John Williams: Concerto for Tuba and Orchestra

Gustav Holst: The Planets, opus 32

Alan Baer (Tuba), Sheryl Staples, Lisa Kim (Violins), Cynthia Phelps (Viola), Carter Brey (Cello)

Women of the Oratorio Society of New York, Kent Tritle (Conductor), New York Philharmonic Orchestra, David Robertson (Conductor)

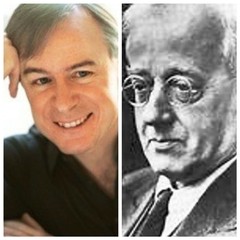

A. Baer (© New York Philharmonic Orchestra)

David Robertson conducted two British Imperial masterworks as bookends last night. But all eyes–and most certainly all ears–were open for the work in the middle.

As First Chair (or only Chair) of the NY Philharmonic Tuba Ensemble, Alan Baer was about to give vent and breadth to an instrument which Peter de Vries called “the bowel of the orchestra”. His choice of concerto, by John Williams, a one-time tubaist himself, gave no notice to a Dixieland band oompah, and certainly wasn’t in the Tubby The Tuba range. After all, Tubby was condescendingly paying homage to an instrument beloved by Mahler, Strauss, Wagner and Ravel.

Nor did it had the excitement, spirituality and heavenly sounds from the various Tuba mirum sections of the Requiem Mass. (A bad pun that. “Tuba” was Latin for “a hunting trumpet”.)

In fact, while this was not Mozart or Berg, John Williams’s Concerto For Tuba and Orchestra, written two decades ago, has long ago replaced Vaughan Williams’s challenging but boring Bass Tuba concerto. It displays the temperament of a legitimate instrument. And it shows the inspiration of a composer who loves the instrument, and has used it for solos from cinema’s Fitzwilly to Star Wars and I beyond.

I have no doubt that had Berio or Ligeti, tackled the tuba, they would have blurted out soprano bel canto arias or breathy notes without tone, or violin-type glissandi. But John Williams simply wanted us to hear the tuba as tuba from top to bottom.

And, so far as I could tell, Mr. Baer executed all of this with apparently extreme ease, with pleasure, and with far more noticeable dynamics than one would hear when the tuba brings up the trombones in the middle of an orchestra.

The first movement gave us a beautiful tuba solo at the start (perhaps to familiarize us to the sounds and range), some delicious interplay with the orchestra and a short cadenza. The central Adagio was not to my liking: too little tuba, too much wind ensemble, not much in which we could revel. But the third movement, an Allegro molto was exactly what we would want from any artist. Triple tonguing, wide expanses on the valves, and the loud, resonating brassy sound in the bass of the tuba. That sound, beloved of all late 19th Century composers (except the always correct Johannes Brahms), resonated up to the David Geffen rafters, and was a tribute to an instrument which has only rare homages.

D. Robertson/G.Holst (© MichaelTamaro/MusicwebInternational)

Not that Mr. Baer was finished. Far from it. Unlike more celebrated instrumental soloists, Alan Baer had to join his ensemble again. For Gustav Holst’s Planets uses a pair of tubas, as well as six horns, four trumpets, three trombones, an offstage chorus of female voices, and all the accouterments to make the solar system whirl.

I can’t say that Alan Gilbert couldn’t have done a better job, since I haven’t seen the NY Phil Music Director conduct this. But David Robertson is as much a dancer as a conductor. Any conductor needs the utmost grace and coordination to summon up all these instruments as solo (Carter Brey’s three magical measures) or ensemble (like those huge consort of brasses). And Mr. Robertson has all the Astaire-style steps to make them come alive.

Mr. Robertson had a more challenging Planets last year, when he used the solar system itself to bring together all the great instrumentalists of Australia and the Sydney Symphony. Then, he had the Internet to give an extra-galactic kick. Here, all he had was one gigantic orchestra, one offstage women’s chorus (which was suitably mysterious in the final Neptune), and his own thrusts and parries.

Gustav Holst himself considered Planets was a cross to bear, its popularity exceeding everything else he would do in his troubled life. But this is far from a burden: much of the music–Mars, Mercury, Jupiter and Uranus–is wildly exciting, while the quieter sections show the same mastery of the orchestra which Mr. Robertson showed here.

With these final two bonanzas, one could almost forget the opening, Elgar’s own version of a concerto grosso. While the solo quartet had a lackadaisical opening, Mr. Robertson soon got his orchestra and four string soloists in gear.

My own problem with Introduction and Allegro is that I feel so guilty sitting in an audience, surrounded by strangers. We have two moments here–the first a few measures before the fugue, the other a few moments before the ending–which are so intimate, so withdrawn, that one feels ashamed hearing Elgar’s innermost thoughts, those few seconds when he escaped pure musical lusciousness for a terrifying confession.

Mr. Robertson, though, acknowledged that all was inevitably Right and Proper in Elgar’s pre-Freudian, pre-genocidal Edwardian world.

CODA: In vain did I wait for a squeak or squawk during The Planets, since the Phil had been joined by five young players who had never been with our orchestra before. The Phil’s “Global Academy Fellowship Program” selected this quintet from Rice University’s Shepherd School for lessons and chamber-music training. But the three violinists, one violist and one double-bass joined their senior colleagues under David Robertson. And so far as I could tell, not a blooper was created.

Not to forget, it was the Alec Baldwin Foundation which helped sponsor them. An always versatile actor, this may be one of Mr. Baldwin’s most unusual roles.

Harry Rolnick

|