|

Back

Tiitian Colors and Choral Tones New York

St.Thomas Church, 1 West 53rd Street

03/18/2016 -

Sir James MacMillan: The Seven Last Words from the Cross

Sir John Tavener: The Last Discourse – Svyati

John Taverner: Quemadmodum

Sherezade Panthaki (Soprano), Glenn Miller (Bass), Myron Lutzke (Cello), John Feeney (Amplified double-bass)

Orchestra of Saint Luke’s, Saint Thomas Choir of Men and Boys, David Hill (Guest Conductor)

St. Thomas Choir (© Courtesy of the Artists)

Before a note was sung last night, I was totally stunned. This was my first time in St. Thomas Church, and the gorgeous screen in front of the congregation behind the dais on the pulpit was absolutely staggering. Possibly the largest in the world, at 80 feet high, 43 feet wide, looking like it was constructed from 100,000 elephant tusks (thankfully, Kentucky stone), this Great Rerodos is packed with images, icons, lacy carvings and enough paraphernalia to make an Indian temple gateway look almost sparse.

A minute after that stunning moment, the 55-odd members of the St. Thomas Choir of Men and Boys appeared in the most ravishing cardinal-red vestments. That contrast of red against the giant grayish-white screen was almost like being part of a Titian painting. No matter what the setting, the music had to be inspiring.

Which it was. It was certainly apt for Lent, with two Passion variations, two or three religions, rolling over five centuries. Even more important, the Choir and St. Luke’s Orchestra were conducted by the great David Hill, notable both in the United Kingdom (Chief Conductor of the BBC Singers, Musical Director of the Bach Singers), and in the United States, as Principal Conductor of the Yale Schola Cantorum.

His confidence and evident mastery was necessary, of course. Not for the St. Luke’s Orchestra, which can handle anybody. But the Boys Choir, some of whose members looked hardly eight years old (though most were in their teens), needed him. And in parts of the MacMillan oratorio and Sir John Tavener’s Last Discourse, the boys had to sing with full voices in minor-seconds, a task which they handled as if born to be psalm-singers.

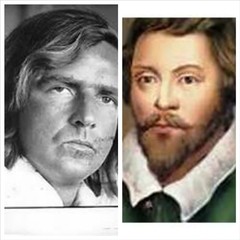

Sir J. Tavener/J. Taverner (©Vintage Amazon/Public Domain)

This concert was unique in bringing together both of England’s John Taverner and John Tavener, both of them near-apostates.

Yes, the 16th Century John Taverner was born Roman Catholic, but was jailed for being a “Lutheran” heretic, though a Cardinal had him released since he was “merely a musician.” His Quemadmodum was, typically, a canonic form, six voices divided among the Choir-members, with repetitions leading up and down the octaves. Perhaps it was the original stunning visual image, or perhaps the Taverner method of clarity in even the most complex sections, but it could only be deemed spiritual.

Sir John Tavener (an almost coincidental name for the late 20th Century composer, dying in 2013) was another apostate of a sort. Born into the Established Church, he was attracted by the mysticism of the Russian Orthodox Church, converted, and composed the music of his last years totally in that form.

The Syvati is used for the closing of the coffin and of course prayers for the after-life. Here, instead of the usual Metropolitan (the priest, almost always a deep bass), Taverner gave us a cello, played by the St. Luke’s Orchestra’s Myron Lutzke.

One must be excused for thinking this work was more Hebraic than Russian. The cello is very much a “Jewish” instrument, the exotic modal scales were probably based more on the Byzantium predecessors than the modern Russian Church, and thus more “Eastern.” Yet without thinking that, the short work had, again, a spiritual power. Sung in Church Slavonic, it finished with the Boys Choir softly repeating the last words. It was breathtakingly beautiful.

Sir John Tavener’s longer work, The Last Discourse was written for St. Paul’s Cathedral, with chorus on ground level, bass and amplified double-bass a level up, and the soprano in the “whispering gallery” unseen. In this case, the Choir was in front, and neither soprano nor low solos were to be seen.

The effect of basses Glenn Miller and John Feeney, again was a composer’s license of the solo Metropolitan in the Russian Orthodox Church. But in this case, another miracle was born in the soprano voice of Sherezade Panthaki.

I had heard her before in both Bach and Mendelssohn, and have never ever forgotten the purity, the almost unearthly beauty of Ms. Panthaki’s voice. Not only is her vocal line clear, chaste and with consummate perfection, but in the areas of this complex work where she must suddenly rise to the highest notes, it was accomplished without effort but seemingly an inevitable movement. In vocal terms, hers is a force of nature.

The 21-member string-section of the St. Luke’s Orchestra was featured with the longest work, Scots-Catholic composer James MacMillan’s Seven Last Words From the Cross.

Mr. MacMillan was unknown to me, and the first few lines sounded like a Britten clone, a Scottish Ceremony of Carols. Yet, within the seven sections here, he varied styles so much that he soon found his original voice.

The second, Woman, Behold thy Son! was fierce and exciting, with the boys repeating the title over and over again as the strings became more frantic. The following piece was almost romantic. Thou Shalt Be With Me In Paradise, was composed with a high violin solo weaving in and out from the Choir, in a complex tapestry.

Throughout the entire work, Mr. MacMillan used silences, not as affectations or spiritual quietness, but as part of the whole language–or series of languages. The final section, Father Into Thy Hands I Commend My Spirit started with the Choir, but subsided into the strings alone. The music here resembled Lutoslawski and Pederecki, a disconcerting end to this very strong work. Yet nowhere did composer MacMillan depart from a deeply-held spirituality, and nowhere did Mr. Hill’s baton falter from leading his singers from whispers to full-voiced orisons.

Harry Rolnick

|