|

Back

Béla Bartók Splits The Czech New York

David Geffen Hall, Lincoln Center

02/25/2016 - & February 26, 27, March 1, 2016

Antonín Dvorák: Carnival Overture, Opus 92 – Symphony No. 8 in G major, Opus 88

Béla Bartók: Violin Concerto No. 2, BB 117

Baiba Skride (Violin)

New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Christoph Eschenbach (Conductor)

B. Skride (© Courtesy of the Artist)

Many years ago in Hong Kong, I reviewed a world-class violinist playing Béla Bartók’s Second Violin Concerto. While praising most of the performance, I disparaged his long first-movement cadenza.

Why (I asked) does a fiddler with such marvelous intonation play so many notes in the cadenza which don’t hit the target? A bit too high, a bit too low.

(Gulp) That was before I learned that Bartók used quarter-tones higher and lower than the “correct” note. Later–through a few months in Hungary and a few more months studying the composer himself–it was apparent that our diatonic scale was only the start for a man who relished both the off-kilter rhythms and off-perfect notes for his own music.

The 35-year-old violinist Baiba Skride, coming from Latvia, with its present plethora of atypical composers and artists, knew this instinctively in her New York Philharmonic debut yesterday evening. Playing with a Stradivarius loaned to her by fellow Balt Gidon Kremer, she seemed to understand instinctively how to get the most out of her instrument, as well as this wonderful work.

Ms. Skride, under the baton of Christoph Eschenbach, started, after those harp/pizzicato strings, with a tone eschewing pure lyricism, instead working with a kind of growl. Not harmful but puzzling, as if she wanted to go into other worlds.

And Bartók provided those worlds in a movement which was played sometimes with the softest lyricism, and then suddenly went into a Vivace dazzlement. The work may be straight sonata form, but Bartók never intended to ignore the sound of surprise. Ms. Skride paused for a moment as the ersatz-atonal measures came through, and she never soared though the cadenza, but let the arpeggios, the double– and triple-strings unravel (as well as those most natural quarter-tones).

The finale was played with a tone ranging from savagery to a conscious mathematical conundrum of agitation and lyricism. Yet at the end, one thought less of these movements as the variations of the Andante tranquillo.

Nowhere did Bartók use the word “tranquil” with more appropriate tranquility. Nor did the composer ever develop a more magical single theme. Unlike the Magyar music, this melody is strange yet pure, a little bit “off” yet with the echoes of the composer’s “night music”. Ms. Skride never offered a saccharine note, but the emotion was obvious. She played each variation with both soloistic ecstasy, and–when calling for in the second variation–as a fitting, almost modest adjunct to the orchestra.

It was a glorious performance by a glorious soloist. Her first partner, the New York Philharmonic, was new to her. But Christoph Eschenbach had conducted her previously, and she obviously felt at home with him.

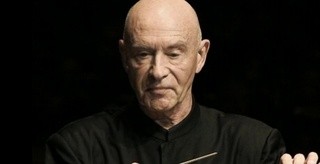

C. Eschenbach (© D.R. Central Picture)

As did the Phil. And the audience. For Mr. Eschenbach is a familiar face (or back) in New York. And while equally experienced conductors let their guards down at times, his animated precise, always exciting conducting probably gives extra confidence to the ensemble.

They needed it too in the opening Dvorák Carnival overture, because I’d never heard it played so rapidly. And for one who adores each note of Dvorák’s orchestral/chamber music (not his choral pieces), seeing those themes come and go so quickly is not very satisfying.

After the Bartók, though, Mr. Eschenbach allowed Dvorák to project sheer joy. Yes, the Eighth is an old standby, but never less than welcomed. Mr. Eschenbach offered all the right stuff–birdsong in the second movement (presaging the Phil’s “Messiaen Week” in March), a scherzo which was never oleaginous or soapy but always danceable, and horns which sounded like Australian bull-roarers in the finale.

This was Christoph Eschenbach with both fervor and, as always, exemplary aplomb.

Harry Rolnick

|