|

Back

Airy Songs and Mortuary Bells New York

Theresa L.Kaufmann Concert Hall, 92nd Street Y

01/31/2016 -

Enrique Granados: Danzas Espanolas, Opus 37: No. 2 in C minor “Oriental” – Goyescas (Los majos enamorados), opus 11

Modest Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition

Garrick Ohlsson (Pianist)

G. Ohlsson/Goya painting (© 92nd St Y)

After Jordi Savall’s brilliant musical picture of 16th Century Spain last night at the Met Art Museum, the most recent entry for the 92St Y “Seeing Music” programs could have been, should have been Música espanola Part II. Yet something was lacking.

The first half of Garrick Ohlsson’s recital was devoted to Goyescas, those six extended character pieces taken from Enrique Goya’s 63 early pictures showing, even satirizing the dashing young Spanish men and their young women. These were not Goya’s war pictures, the tortured precursors to Picasso’s Guernica. They have the lightness of Renoir or Seurat (though much earlier), and were the obvious choice for Enrique Granados, himself a dashing young pianist composer, who wrote the works 150 years after the original.

And they do have their charms. When Alicia de Larrocha played Goyescas, the notes leaped out of the piano. When Mr. Ohlsson performed, the phrasing was more elegant, the long runs could have been Liszt at his most challenging.

Still, after one hour of light syncopation, with every third note turned around with two or three ornamental mordents, one was ready to give up. This had nothing to do with Garrick Ohlsson. He is a big man with big hands, and the music, whether bold and sweeping (like the first Goyesca, “The Compliments”) or with grand crescendos (“Conversation by the Window”), or a dashing fandango, was taken it its stride by Mr. Ohlsson.

Unlike Mr. Savall’s dramatic songs and dances from the Cervantes Era, the Goyescas were elegant, fastidious when necessary, they were of salon quality but extended out for more dazzling piano-play. Mr. Ohlsson is an engaging personality on the piano. Yet one could imagine the middle-aged Enrique Granados playing, say, the folkish tune of “The Girl and The Nightingale”, and instead of finishing it, working in some nightingalish trills, turning to his audience, winking at the lovely young damsel in the third row.

The following might be unfair, but when I visited Granada’s Carlos V Art Museum in the Alhambra many decades ago, one huge galley was devoted to Spanish Renaissance pictures of the Passion, in agonizing detail. Music from the background loudspeakers was the dark male-choir Renaissance/Baroque polyphony of Guerrero and Tomás Luis de Victoria. A few rooms away were the 20th Century paintings which the dictator Francisco Franco loved so much. Lovely girls in crinoline, men and women sitting adoring each other (never touching, of course) and families of happy people out for a Sunday walk (after a church service of course).

The music in that background was Franco’s favorite. Just as Hitler preferred Franz Lehár to Richard Wagner, Franco preferred Granados to de Falla.

Did that influence my experience yesterday? Perhaps. But in the second half, Mr. Ohlsson redeemed himself before the packed audience. Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition takes half the time of Goyescas. Yet every measure, every “picture”, every emotion, every single bar of this masterwork flings open the doors of imagination.

That is, if the pianist understands what he is doing. I once heard a famous pianist play this with the skill of the born pianist. The problem was that he never understood that Mussorgsky’s homage to Viktor Hartmann, his friend who had died at the age of 39, was not symbolic or adoring or a piano piece. Mussorgsky was neither “translating” the pictures into music, or doing a Richard Strauss trick of literal aural image. Rather, he was performing a 30-minute Eucharist virtually transubstantiating colors into tones.

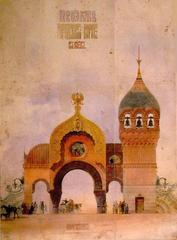

Hartman’s Great Gate at Kiev (© en.wikipedia)

Mr. Ohlsson knew this instinctively. Hartman’s paltry draftsman-like plan of the Kiev Gate became under Mr. Ohlsson’s hands a series of gates, from the simple architectural lines at the beginning to the monumental medieval portcullis at the end. He played the Bydlo, that rickety bullock-cart, as though the wheels were stuck in the mud of Siberia: it was heavy, clunking, coming down on its own.

And speak about lightness. The Gnomus was played like a conglomeration of Spielberg’s elves: darting light and heavy, cute and ferocious, menacing and adorable. While the Tuileries buzzed with excitement. “Rich Jew” and “Poor Jew” were portrayed by Mr. Ohlsson like an anti-Semitic cartoon of the time. His tycoon was tired, shambling, heavy coat, heavy scarf. Behind him was his unwanted country cousin. Somehow Mr. Ohlsson made him cackle, implore, begging for a few drachmas...just enough to buy candles for the Sabbath.

It would be unfair to say this was Garrick Ohlsson in his element. He is a Chopin man, as his encore showed (hamming up a Chopin waltz as an encore is permissible). But since this program was to explore the confluence of painting and music, his might and his imagination generated pictures which would have dazzled Mussorgsky himself.

Harry Rolnick

|