|

Back

Fanfares, Black Ties and Cadenzas New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

10/07/2015 -

Magnus Lindberg: Vivo (World Premiere)

Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat Minor, Opus 23

Maurice Ravel: Daphnis et Chloé: Suite No. 2

Evgeny Kissin (Pianist)

New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Alan Gilbert (Music Director and Conductor)

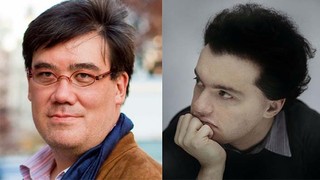

A. Gilbert/E. Kissin (© New York Philharmonic

One-hundred and twenty-four years and six months prior to the Gala Opening Night of the 2015-2016 Season, the first official opening of Carnegie Hall boasted the appearance of the most famous Russian composer in the world. The lanky elegant figure of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky mounted the same stage to which Alan Gilbert mounted, they both raised their batons, and the audience in the same grandiose auditorium heard those same iconic chords of the First Piano Concerto.

The performer at that time was Adele aus der Ohe, a prized student of Liszt barely known today. Nothing obscure, though, about Evgeny Kissin. In fact, he has been performing in public for 34 of his 44 years, his greatest early triumph the same Tchaikovsky Concerto performed with a dazzled Herbert von Karajan at the age of 17.

Any appearance of Mr. Kissin is a gala appearance (and he will be performing several times in Carnegie Hall this season). Last night, though, was the gala Gala Opening for the season. The audience, highlighted by New York’s Great, Good and (obviously) Generous, were dressed for the occasion. Those going to the after-concert roof-party in tuxes and diamonds, others in their best apparel, Isaac Stern Auditorium packed to the gills. No intermission last night, no chance for any guests to sneak out of the hall. For they were to be treated not only with Mr. Kissin but a rousing Star-Spangled Banner (was this the Toscanini orchestration?), a world premiere to start and a finale with the New York Philharmonic showing off vibrant colors that the fashionable elite could only dream about.

That world premiere (co-commissioned by Carnegie Hall), by last year’s NY Phil composer-in-residence, Magnus Lindberg, was the least impressive part of the evening. An explicit pièce d’occasion, Mr. Lindberg explained that he was “asked to write a concert opener for Carnegie Hall’s Opening Night Gala, which is obviously a special occasion...”

Mr. Lindberg is unfailingly deft, dextrous, with a singularly lively orchestral genius. And in his Vivo, he had packed fanfares, contrasts of different themes, big, almost blustery passages, filled with percussion–and finishing strangely quietly.

Doubtless, Mr. Lindberg had some musical subtexts (he had mentioned a harmonic relationship with Daphnis et Chloé), but to these ears, it was hardly amongst his great works. Hardly in the kitschy class of, say, Shostakovich’s Festival Overture, its pleasure, though, ephemeral.

Nothing is ephemeral about the performances of Evgeny Kissin. He is unfailingly dynamic, lyrical when the occasion suits him, always a massive presence. He has obviously matured in these past three decades, but the Tchaikovsky is such a monumental work that his own monumental work, if hardly changing, is hardly unexpected.

Alan Gilbert accompanied with as much aplomb as possible, his soloists (notably cellist Carter Brey) were suitably impressive. But this piece rarely shows off the orchestra. It is in the hands of the soloist.

Mr. Kissin started those most familiar chords firmly rather than over-dramatically. He could play with the orchestra (that staccato dialogue with winds at the end of the intro). And while he could go through those fast run with machine-like drill, he could launch into an emotional cadenza, then a few measures of real personal intimacy before the overpowering climax.

Some take the slow movement as the prelude to the dizzying waltz interlude, but Mr. Kissin understood how cohesive it can be, and this was a seamless Andante semplice. The finale is marked con fuoco (with fire), with Messrs Kissin and Gilbert were ready to conflagrate the hall. It was animated, red-blooded and guaranteed to have the audience standing as one, pleading for more.

Mr. Kissin obliged with a Tchaikovsky encore, Meditation. That was a salon piece, hardly in the Concerto league, but finishing with Mr. Kissin’s thrilling trilling, the sounds diminishing to a quiet amen.

For the finale, Mr. Gilbert cast aside his baton. Why paint Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé with a single brush, when you can use ten different brushes striking out in ten different directions? Ravel’s impressionistic Greek lovers didn’t need a blurred texture, but the “rivulets of dew trickling from the rocks...the young nymph wandering in the fields” (Ravel’s own words) did need “a bright golden haze in the meadow” (Oscar Hammerstein’s words). And perhaps Mr. Gilbert felt the glow would be more radiant with each finger summoning up the instruments.

R. Langevin (© New York Philharmonic)

Obviously the New York Philharmonic, inspired partly by the resounding acoustics in Carnegie Hall, was up to the task. Yet at the end, one was awed not so much by the atmosphere or the frenetic finale as the solos by NY Phil Principal Flute Robert Langevin.

Mr. Langevin has been described before in these modest pages, yet nothing, absolutely nothing can describe the purity of the very first solo here, and its continuation throughout the entire Second Suite. Actually, the flute personification played by Daphnis/Pan in the ballet was almost anti-climactic. One expected it to be perfect flute-playing. More breathtaking, coming out of the orchestral texture, Mr. Langevin offered the intangible aura of the entire piece.

As expected for this Gala Opening, Mr. Gilbert let all the energies flow into that grand sweeping finale, the kind of Boléro/Valse finale for which the composer excelled. The orchestra gave off a Champagne fizz. Unavoidably, it would be more authentically fizzier than the bottled stuff which Black-Tied/Diamond-crusted elite would sip after Mr. Gilbert’s effervescent opening.

Harry Rolnick

|