|

Back

Better Home and Gardens: The Musical New York

Avery Fisher Hall, Lincoln Center

07/17/2015 -

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 6 (“Pastoral”), Opus 68

Richard Strauss: Sinfonia Domestica, Opus 53

The Cleveland Orchestra, Franz Welser-Möst (Conductor and Music Director)

F. Welser-Möst (© Roger Mastroianni)

For his penultimate New York concert Franz Welser-Möst started last night with (apologies to Stephen Sondheim), Friday in the Park With Ludwig.

It was supposed to be Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony, and with the Cleveland Orchestra playing more storm than the fourth movement Tempest, this was inevitably a joyous experience. And if Maestro Welser-Möst avoided any of the composer’s directions of non troppo or allegretto, he was permitted. For the conductor was putting himself in the conductor’s scruffy well-worn hiking boots last night.

Literally!

Not even Mr. Welser-Möst would have intimated a personal alliance with Beethoven. But the Sixth Symphony evidently was Beethoven himself taking a country walk. And, despite his short stature, one can’t imagine him simply walking or strolling around the Vienna woods. He would have stamped, clumped and , strode his way around the fauna–and Mr. Welser-Möst played it with that pace.

Nor did he waste much time with the “Scene by the Brookside”. The tempo continued, as if Beethoven had no time for a “scene”, while the brook was more a raging stream. Did those luscious Cleveland Orchestra strings leap ahead of the cellos at time? Obviously Beethoven might have tripped and gotten straight up (cursing at the damned stones). Were the flute bird-calls a bit too Arcadian for the tempo? Well, Beethoven might have loved nature, but Man (himself, of course) was superior to mere landscape.

At any rate, this was a delectable Sixth Symphony. When Mr. Welser-Möst allowed the “country-folk” to have their raucous festivities, when the sudden rainstorm pushed them under the trees, the Cleveland Orchestra lower strings and thunderous timpani were as literal a picture as Richard Strauss would have composed.

Mr. Welser-Möst didn’t let down his guard for the finale, but his tempo became relatively more tranquil, the sunshine of the strings and the rainbows of the winds ended Ludwig’s “Friday in the Park” with the most satisfying final chords.

If this feeling was more personal than musical, Richard Strauss’s Sinfonia Domestica was the ideal complement to Beethoven’s clippety-clop outdoor adventure. Beethoven might have tried to hide his subjective sauntering. But Strauss never masked his subject that way. Sinfonia Domestica was not so much a “symphonic poem” as (with apologies to the Beatles) A Day in the (Bourgeois Strauss) Life.

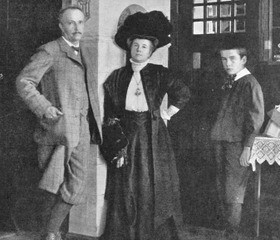

R., P., F. Strauss

As this picture shows, Strauss, his wife and his son Franz (soon to be a noted doctor) was–outside of his genius–that most bourgeois of composers. And while the subjects from most of his early tone poems–the two mighty Dons, the Hero’s Life, the ascent of the Alps–were Promethean, Strauss, like Beethoven went thematically minimal here. No hangings, no sword fights, no tilting at windmills…even the passion was a marital cuddling between husband and wife. Nothing interfered in this domestic tranquility: wife, baby, a game, a lullaby, games, tantrums, dreams, love-making, a “merry dispute” and the finale “joyous confusion.

All with a Gargantuan orchestra, a complex triple fugue, and some of the most underrated effects of color and picture.

While I never heard this played live in New York, recordings from Maazel and Strauss himself are on my computer, and until last night, I was never too impressed. Mainly because I was attempting to hear the configuration of lullaby, clock chiming, the baby in the bath and where the “love scene” coalesced with “dreams and worries.”

Last night, with the suitably Gargantuan Cleveland Orchestra, I listened to the music–and to hell with Strauss’s literal directions. What I heard was sheer (if overblown) orchestral magic. Not just the rare oboe d’amore (played with naive simplicity by Robert Walters), not just the heroic horn duet at the beginning of the slow movement, or the solo violin work by Concertmaster William Preucil, but 45 minutes of pure emotionalism.

The kind of emotionalism which, some decades ago, would have been called “vulgar”, but which today is recognized as unashamed beauty. In some ways, this Sinfonia Domestica overstayed its welcome. The slow movement especially wanders off the tracks at times. But by the finale–with its endless Beethoven-style counterfeit finales–Mr. Welser-Möst was in his element. His careful development of the opening fugues, his triumphal themes, and finally, his arms waving windmill style for the end...

Like the opening night’s Daphne, he had turned this rarely-played Strauss into a work of emotional thrills.

When it was over, he summoned up different soloist and consorts, and the audience roared for the saxes, oboes, timpani, brass and strings like they were stars of an opera. Richard Strauss in 1903 would have appreciated that, If this work wasn’t quite an opera, it was both drama and symphony. Mr. Welser-Möst had the power, understanding and the orchestra to let the composer’s literal images become pure pictorial passion.

Harry Rolnick

|