|

Back

The Fabulous Feast of Fazil Say New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

04/11/2015 -

Richard Wagner: Siegfried Idyll

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 23 in A Major, K. 588

Fazil Say: Chamber Symphony, Opus 62 (World Premiere)

Josef Haydn: Symphony No. 80 in D Minor

Fazil Say (Piano)

Orpheus Chamber Orchestra

F. Say, Orpheus (© Chris Lee)

Fazil Say is a sad example of how, in one aspect, Turkey has deteriorated since the Ottoman Empire. For almost five centuries, the Ottoman sultans cared little about the religions of the subjects in their far-flung imperium. And when brilliant artists were discovered–whether Muslim or Orthodox or Catholic or sometimes even Jewish–they were enlisted to help design, paint, sculpt or draw the great Ottoman structures seen even today through Central Europe.

Unless an unknown Sufi wizard is hiding in Anatolia, no musician is more brilliant than Fazil Say. But he had the chutzpah to quote from an ancient revered Persian poet, Omar Khayyam, in a Tweet about fundamentalism three years ago. The result was that an Istanbul court found him guilty of “hate speech”, and he was named an apostate. Today, he is free so long as he remains “in good behavior”.

Sigh.

Well, religion (or its aberrations) aside, Mr. Say was on his best behavior last night, both as performer and composer. Though “best behavior” hardly sums up his wondrous gifts.

In fact, his piano performance with the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra was idiosyncratic Mozart at its most exhilarating. As for Fazil Say’s Chamber Symphony, this deserves to be a classic amongst string orchestras, and–though they don’t deserve it–an homage to the music of Turkey itself.

The Mozart first. I don’t know how Fazil Say would handle late Beethoven, for his jubilation, his happiness and comfort at the keyboard would seem to eschew the forlorn. (Though he might well be flexible enough to handle dour old Ludwig.)

The Orpheus Chamber Orchestra has already recorded this Mozart concerto with Richard Goode, and the pianists are not dissimilar. Both Goode and Say catch the sprightliness, the humor, the bounce of Mozart, both are clear in their lines, and in both, the Orpheus accompany as well as any classical orchestra.

While I have only heard Mr. Goode’s recording, I doubt whether he would possess Fazil Say’s coupling of music with physical bounce. His comfort at the stool meant that when one hand was playing, the other was conducting, and when he came to the cadenza, he happily exaggerated the challenges. (In one measure, I thought he was going to begin the Rachmaninoff C Sharp Minor Prelude, but he continued with the Mozart.)

The slow movement was not the usual Andante, but a heartfelt Adagio. The ending was simply a whirligig of lightness and joy. Mr. Say felt no hesitation in turning ordinary notes into staccato jabs, but he was never hesitant in bring this to an assertive triumphal close.

The post-intermission Chamber Symphony was, surprisingly, totally Turkish. Not the ersatz Turkish Janissary music of Mozart and Haydn, but the full-fledged Turkish scale, those moaning minor thirds, even the popular Turkish orchestration of themes in high and low register playing together.

But this never–and I mean never–stopped Mr. Say from composing a work whose ethnic character was supplementary to its unfailing energy, his mastery of counterpoint, his unfailing inspiration. The single movement was divided into fast-slow-fast, and the first section, with all its Turkish flavor, was combined with string tricks, oleaginously-funny glissandi and complex tunes. The slow section had some Bartók night sounds, followed by a pleasant waltz. And in the finale, Fazil Say took his music to the Bartókian ultimate, creating a musical map with rhythms that could have been Turkish, Rumanian, Bulgarian and, yes, Hungarian.

The Chamber Symphony was far more than a romp. It was, like Mr. Say’s Mozart performance, hearty, rambunctious and masterfully created.

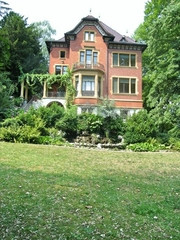

Siegfried’s and Idyll’s Lucerne birthplace

(© Sam Von Doggenstein)

Compared to Mr. Say’s so buoyant music, the opening and closing works seemed inevitably lackluster. This wasn’t entirely the Orpheus fault. Richard Wagner’s Siegfried Idyll was more than a birthday gift for his newborn son. It could have been a painting of Wagner’s spacious lawn north of Lucerne, the sun coming through the windows, his dog romping over the sward, the idyllic music played by the musicians on the staircase led by the composer himself.

Picturing that, the strings of the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra sounded tentative, not so much lacking energy as simply playing by rote. The Orpheus musicians attempted to create moods and images, but instead showed off their good music-making. When the winds chimed in, one felt at least an impetus, an effort to push this “Wagnerian music” into the region where it should be, as a 19th Century tone-poem which at times excelled Liszt’s attempts at the same form.

Nor did the Haydn 80th Symphony approach either the composer’s mournful beginning or the frisky jokes of the finale. With all the honor due to the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, now approaching its 40th year, some music does need a conductor. Yes, those strings played the opening movement Schubert-style waltz with some aplomb, and skipped faultlessly through the Presto movement, the surprise pauses and syncopations taken with utmost precision. But one wonders what a conductor would do with the forebodings, the tricks and pranks and always startling changes.

The Orpheus takes pride in taking energy from its own players, from its “core musicians”, and they do very well. Yet, imagine what a Gilbert or a Norrington or a Dudamel could do, not with this full ensemble, but in punctuating and underlining individuals literally encountering each other.

That comment, though, for the Orpheus, could be considered apostasy. One apostate a night–even if "heretic” Fazil Say has the marks of genius–is quite enough.

Harry Rolnick

|