|

Back

A Mass-ive Attempt at Inspiration New York

Avery Fisher Hall, Lincoln Center

03/09/2015 -

Giuseppe Verdi: Messa da Requiem

Jennifer Check (Soprano), Ann McMahon Quintero (Mezzo-soprano), Steven Tharp (Tenor), Wilhelm Schwinghammer (Bass), Bebe Neuwirth (Narrator), John Rubinstein (Rafael Schächter)

The Collegiate Chorale, James Bagwell (Music Director), Ted Sperling (Artistic Director), Orchestra of Terezín Remembrance, Murry Sidlin (Creator/Conductor)

M. Sidlin (© Jeff Roffman)

If Steven Spielberg ever needs a sequel to Schindler’s List, the story of the Terezín Requiem is impeccable.

Think of the prelude: A young American conductor, himself related to those killed in the Holocaust, finds an old book called Music in Terezin, is inspired by the story to make an oratorio about a musical miracle in the Second World War.

Now the story. In a a relatively “liberal” World War II Czech work-camp housing 150,000 Jews, a young handsome classically-trained Rumanian-Jewish conductor, has carried books of his favorite music, including a single score of the Verdi Requiem. There, under the sneering eyes of the Nazi guards, the conductor trains the Jewish prisoners to sing by rote until they have a performance ready. No orchestra, of course, but the tin-pan piano is good enough for such a stirring work.

They are so good, in fact, that they give 16 performances of the Requiem, including one for the Nazi hierarchy, who sit in the front row with the Red Cross, enjoying the show, the same way slave-owners enjoyed minstrel shows. The end is tragic. The conductor is sent to Auschwitz, and dies on a death-march, though a few of the original chorus members tell their tale, the way survivors told their own stories in Schindler.

A fabulous movie concept with all the elements. If Mr. Spielberg isn’t interested, let’s go to Martin Scorsese, who knows more about Italian music than any American director today. Or my own choice, David Cronenberg could make the Terezín Requiem movie, showing the grotesquerie of playing the most magnificent religious music in front of the world’s most evil men.

Better yet, an opera could be written to commemorate the event. Steven Stucky could interpolate the Requiem in this opera the way he worked Mozart into his opera about Charles Rosen. Perhaps he might sneak in an even more important concentration camp event, Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time, offering the commonality of beauty amidst the beasts.

That original story could have been told in a dozen different ways. So it is unfortunate that Murry Sidlin, the conductor who had found the book, has created a “performance-piece” which is not only clumsy in conception but cloying in emotion, and convoluted in structure.

The stage (© Yuan Lei)

The conception never fits any category. This was not billed as the Verdi Requiem at all, but a Defiant Requiem, though one cannot help but be repelled by the mongrelization of this great work. Putting that aside, he produced an uncomfortable merging of varying composites, starting with a huge screen showing the entrance to the camp. Later on this screen behind orchestra and chorus, we hear testimony from the survivors (with the exact same backgrounds as Warren Beatty’s movie Reds). We also have a “staged Nazi movie”in black-and-white about the “euphoric” days at Theresienstadt. Interesting enough, but adding little to the story.

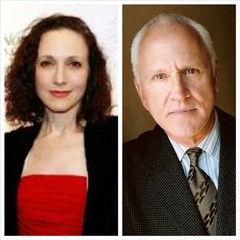

B. Neuwirth/J. Rubinstein (© Courtesy of the artists)

Sitting uncomfortably (and, compared to the mammoth screen, like Lilliputians) in the orchestra are two actors, Bebe Neuwirth and John Rubinstein, offering their own comments on the performance. These are followed by comments from conductor Murry Sidlin himself. Musically, concertmaster Herbert Greenberg plays Bach at the beginning and an old Jewish synagogue melody at the end. A piano plays sections, segueing into the orchestra when necessary.

How would Giuseppe Verdi have reacted to this awkward conception? Those who have studied Verdi’s personality would know that he would have approved–in theory–with this drama/testimonial/concert/movie. Like Toscanini, that most humanistic composer in the Second World War would have left Italy, refused to appear in Germany, and would have represented the Allies against the Fascists.

But one doubts that Verdi would have agreed with the execution, although the audience might have been moved about the presence of music amidst the horror. And yes, the testimonies about surviving through music, were truly poignant, truly soul-stirring and appropriately hagiographic. Nor could anyone doubt that the 39-year-old Rumanian-born Czech conductor in the “work camp”, Rafael Schächter, was a great man whose loss was more than tragic.

But that could have spoken for itself. Mr. Sidlin augmented the stirring story with far too much musical hokum. Since he was telling a story, he might be forgiven stopping in between sections of the Requiem to give more testimonies, more tributes. But some of it was unforgivable.

Specifically, how dare he give a fiercely loud choral sound at the end, when Verdi calls for piano pianissimo? That, I learn was supposed to be the sound of a train whistle, yet the effect was anything but portentous. Or what reason did he have for suddenly altering tempos, changing the score?

Well, it was his show, his responsibility, so we had to live with it.

Musically, Mr. Sidlin’s creation was only fitfully impressive. The grandly-named “Orchestra of Terezín Remembrance” was a decent enough New York pickup orchestra with too little rehearsal. The notes were right, the texture was missing. Of the four soloists, tenor Steven Tharp, had a rich, operatic bel canto voice which truly stood out. Bass Wilhelm Schwinghammer was unsteady at the beginning, improving as he went along. And one knows that, had Verdi been present at the rehearsal, he would have coached soprano Jennifer Check not to swoop upward, not to shout, not to attempt reaching for those high notes with great volume, that for all the operatic structure, this was still a religious piece.

Most tragic was the Collegiate Chorale. They were either overwhelmed by the orchestra or never quite worked into the spirit of the Requiem. Not that the Collegiate Chorale can ever be amateur. But those choruses which should be passionate, pleading, infernal and heavenly became blocks of static sound. The Collegiate Chorale has sung the Verdi Requiem many times, but perhaps they felt it insulting to be interrupted so frequently by dialogue and a movie pitchers show.

Conductor Murry Sidlin should have known better. He has studied with the finest conductors, is highly experienced, and–as having had relatives who died in the Holocaust–must have the inner sensations to bring this singular story to life. The fact that he has taken his show on the road–through America and even to the Czech Republic–shows that he has not been unsuccessful in his efforts.

To some of us, though, we should have been stirred by the story behind the music, and certainly always aroused by Verdi’s most fervent music. And this was almost nonexistent. I wish that somebody had suggested to Mr. Sidlin that his finale was a damper. A long long dampening ending as Mr. Greenberg played his violin, and the massive orchestra and chorus solemnly clumped off stage, down the steps, walking up the aisle to the exit, and out to the subway, while the audience was told that “out of respect”, they were not supposed to applaud. How much more effective than this long-winded ending, I feel, would be a simple darkening of the stage, the violin and the silence. The complexity of the program deserves a simplified conclusion

I studied the audience sauntering out but detected no emotion, except that some said, pie-faced, stolidly, “Well, that was certainly a good experience”, and then look for the nearest taxi.

I personally walked out with the resolution to read the book, Music in Terezín and prepare myself for the real Verdi Requiem on March 26 in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.

Gilding the Verdi flower with the story behind the unlikely performance is not malevolent in itself. But it takes more than good will and a good story. To transcend this well-meaning hokum, Mr. Sidlin had to bring a professional appreciation of theatrical balance and a respect for the original music.

Harry Rolnick

|