|

Back

Songs of the Earthiness New York

Zankel Hall, Carnegie Hall

03/08/2015 -

Igor Stravinsky: Octet for Wind Instruments

Charles Ives: Scherzo: Over the Pavements

Elliott Carter: The American Sublime (World Premiere)

John Cage: Atlas eclipticalis

Charles Wuorinen: It happens like this

Evan Hughes, Doug Williams (Bass-baritones), Sharon Harms (Soprano), Laura Mercado Wright (Mezzo-soprano), Steven Brennfleck (Tenor)

The MET Chamber Ensemble, James Wuorinen (Conductor), James Levine (Artistic Director and Conductor)

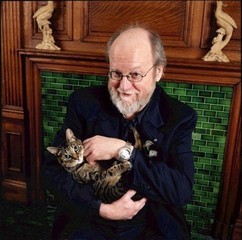

J. Levine (© Huffingtonpost.com)

If modern music had its own Superbowl, this weekend’s big game would have the Nordic Reindeer playing against the Yankee Buffalos.

Explanation. The “teams” were the two best orchestras in New York (NY Phil versus the MET Chamber Ensemble), with a pair of the best conductors in the world (Alan Gilbert vying with James Levine). Both concerts, though, would get their names from their areas of contention. Specifically, Alan Gilbert produced a concert of 21st Century works from Scandinavia and Finland on Saturday. James Levine produced a concert of modern-(sounding) American music on Sunday afternoon.

And the winners were...the audiences!! Two full houses ready to accept the most interesting and challenging music.

The Nordic concert seemed not of this earth at all, but the four composers reached for (and sometimes came close to) the stars. Us Americans are a more material people, though John Cage’s music specifically and literally used a star map to make its points. But the music of Carter, Ives, Wuorinen, and Stravinsky (who in 1924, was probably a Frenchified Russian, not yet an American) belonged to this earth.

James Levine, though, can sit on his motorized vehicle and enthusiastically conduct it all. As he admitted, when giving up his baton to Charles Wuorinen for the final work, he has worked with the best of all composers. And as the late Elliott Carter explained, “the extraordinary James Levine has brought my music to life.”

We saw only Mr. Levine’s back and hands, but that was filled in later in the evening during the late Bob Simon’s profile on the conductor for 60 Minutes. This was the face and smile and expression which brought that music to life indeed. And Elliott . Carter–who had written nearly two-dozen works after he reached the age of 100–was given a lively reading.

Mr. Carter had set the work of a poet he (and we) have always loved. As Mr. Carter loved literature, so Wallace Stevens loved music, and included the power of music in much of his poetry.

“Music is feeling, then,” he wrote, “not sound.” And the music which Mr. Carter set to Mr. Stevens’ The American Sublime was the feeling of an enigmatic large ensemble, painted with pointillistic points for the enigmatic poems. Bass-baritone Evan Hughes has a gloriously full voice and both declaimed and sung the poetry with enormous affection. The last words of each seven poems were extended out, and Mr. Evans has the stentorian tones to give it all the right power.

Yet in a way, I didn’t need that voice. The voice and poetry stand by themselves. The orchestra–a full consort of winds, percussion, piano, trumpets and horn–gave such a colorful account of themselves, Mr. Carter paying attention to even the most minute percussion sounds, that both voice and words were almost irrelevant.

Nothing against Mr. Evans, but Wallace Stevens’ words were music by themselves, and Elliott Carter knew how to decorate those sounds.

The opening piece was the Stravinsky Octet for Wind Instruments, which the composer dreamed one night, then wrote down the dream notes. Historians today call this his first “neo-classic” music, which isn’t quite true. (Mavra has the same 18th Century sounds.) More important is that this is a work of lucidity and color, that color provided by the no-nonsense tempo and by some wonderful fingering by Koren McCaffrey’s flute.

Following this was Charles Ives, for which no introduction is needed. His “avant-garde” Over the Pavements was like early Cage, in that he took the ordinary sounds of the street–people, horses, trolleys (no cars in 1910), different tempos of walking, running, sauntering. And he turned it into an Ives comedy, complete with an unfinished upbeat!

John Cage had an equal sense of humor, though I feel it’s the humor of nihilism. In Atlas eclipticalis, he described his purpose in the aleatory music. “A heavenly illustration of Nirvana should be like looking into the sky on a clear night and seeing the stars.”

I suppose the stars were the rare full playing of the large wind/percussion ensemble, and Mr. Levine conducted (if such be the word) with merciful brevity. Forgive my Luddite temperament, but I don’t like my music to be random, no matter how abstruse and logical the explanation. I guess the musicians liked it enough, but to me it signified nothing.

C. Wuorinen and friend (© Nina Roberts)

The biggest shock of the evening was the final 40-minute cantata/oratorio by Charles Wuorinen, a work so original that James Levine left the conducting to the composer.

The shock was that one never instinctively uses the word “humor’ with this austere atonal composer. What Mr. Wuorinen once said about listening to Pierrot Lunaire–”It’s like trying to befriend a porcupine”–might go for his prickly music as well.

That, though, was before the stately Mr. Wuorinen set the music of the surrealist, funny, grotesque mordant, hilarious poet James Tate. Of his seven poems here, three were about animals–goat (who could be Jesus), dog (who unfortunately was awarded with being a man), wild turkey (the guest of the poet) –and they could have been written by Patricia Highsmith, who also saw animals as weird human-ish figures. The other four dealt with violence, cannibalism, a laundry list of the soul and a candy store. And they all had the fantastical imagination of Roald Dahl.

Mr. Wuorinen created for them a cantata, a funny cantata of speech, monologue, aria, duet, quartet, with the MET’s full chamber ensemble providing the atonal accompaniment. Sharon Harms. Laura Mercado-Wright, Steven Brennfleck and Douglas Williams did the vocal–and acting–honors, for this was a show as much as a cantata. Once again, I would rather read James Tate’s poetry by itself, but if you must have music, this was jocular enough to give radiance to the words.

Like Mr. Carter’s music, It Happens Like This was dedicated to James Levine. And while Mr. Wuorinen conducted, the prints of Mr. Levine on his MET Chamber Ensemble writ large on every note.

Harry Rolnick

|