|

Back

Orwellian Atwood ballet is striking and problematic Ottawa

Southam Hall, National Arts Centre

01/22/2015 - & January 23, 2015

Lila York: The Handmaid’s Tale

Royal Winnipeg Ballet's soloists and corps de ballet: Elizabeth Lamont (Offred), Sophia Lee (Moira), Dmitri Dovgoselets (Nick), Sarah Davey (Serena Joy), Liang Xing (The Commander), Yayoi Ban (Aunt Lydia, Lead Wife), Jaime Vargas (Luke), Eric Nipp (Luke, on film), Alanna McAdie (Pregnant Handmaid), Yosuke Mino (Lead Resistance Fighter); Manami Tsubai, Katie Bonnell, Chenxin Liu, Amy Young, Jaimi Deleau, Yoshiko Kamikusa (Handmaids, Jezebels, Wives), Luzemberg Santana, Stephan Possin, Eric Nipp, Ryan Vetter, Liam Caines, Egor Zdor, Tyler Carver, Thiago Dos Santos (Gilead Men, The Eyes, Officers)

Donna Laube (pianist), The National Arts Center Orchestra, Tadeusz Biernacki (music director and conductor)

André Lewis (artistic director), Jeff Herd (executive director), Lila York (choreography), Amanda Green (solo choreography, The Time After), Liz Vandal (costume design), Clifton Taylor (scenic design), Anshuman Bhatia (associate scenic design), Clifton Taylor & Anshuman Bhatia (lighting design), Sean Nieuwenhuis (projection design)

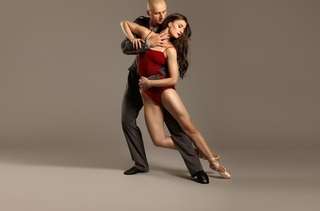

(Courtesy of RWB)

It is thirty years since publication of Margaret Atwood’s dystopian novel The Handmaid’s Tale, which may be the most bleak futuristic fiction since George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-four. The latter was published in 1949 soon after the defeat of Nazi Germany and at the half-way point of the twentieth century --- a defining moment for the world from a huge range of social and political perspectives.

It may or not be coincidence that Atwood, born in 1939, was completing The Handmaid’s Tale during 1984, height of the Reagan era and a peak for the women’s movement, baby boomers, and the sexual revolution. It would be simplistic, indeed trite, to categorize Atwood’s work as a feminist spin on Orwell’s work, though parallels between the stories and their environments are indeed strong. The primary difference is that Orwell’s protagonist is a man while Atwood’s is a woman.

The novel’s origins however go back considerably further than the mid-twentieth century, the title being derived from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. While societal brutality may be a primary theme of The Handmaid’s Tale, structurally and dramatically it is more a series of episodes than a single-plot drama of love, conflict or possible redemption (flashbacks in the ballet also evoke Proust). It may be this episodic structure which prompted Canada’s Royal Winnipeg Ballet and New York choreographer Lila York to attempt a ballet version. (A Hollywood movie starring Robert Duvall, Faye Dunaway and Natasha Richardson was made in 1990 and, more recently, an opera by Poul Ruders was produced in Copenhagen, London, and by The Canadian Opera Company in Toronto for its 2004-2005 season.)

Turning the novel into an edgy modern ballet was a problematic challenge to be sure, but not an unrealistic one. The initial staging in 2013 has been modified significantly (choreography as well as lighting and other production aspects), so the Ottawa engagement is almost a new première. Visually, the work is consistently impressive. The minimalist sets strike a fine balance between atmosphere and functionality. Costumes are more colorful and play a significant role in the ballet’s overall dramatic function (the sleazy tango which opens the second act was particularly memorable). Ms. York’s choreography is fairly conventional (as was that for Pina Bausch’s Vollmond seen in Ottawa and Montreal last November), however is consistently realized and perhaps intentionally invokes reminders of earlier times, for the characters and for audiences. The women’s dancing looks back even to Petipa’s choreography for The Sleeping Beauty, while the men’s is more modern and athletic, a sort of Jerome Robbins plus capoeira --- the opening scene, with warring gangs, torture and executions is almost a neo-Nazi homage to West Side Story. Moreover, the choreography and its concept work well, and are aided by a cast which performs superbly. The standing ovation at the production’s conclusion was very obviously a tribute to the dancers as much as to the ballet itself. Elizabeth Lamont (Offred), Jaime Vargas (Luke) and Dmitri Dovgoselets (Nick) were particularly memorable in their flashback sequences.

Music for The Handmaid’s Tale has been drawn from a range of sources, some familiar (Leonard Bernstein, Alfred Schnittke) and some, less so (James McMillan, Arvo Pärt). It is a brilliant collage and, like the choreography and costumes, plays a major role in defining and unifying the ballet, and was performed superbly by The National Arts Centre Orchestra under the direction of Tadeusz Biernacki.

As dance theatre, Canada’s Royal Winnipeg Ballet’s The Handmaid’s Tale works strikingly and brilliantly. It may not be the final word on Ms. Atwood’s iconic novel. However, it is a worthy accomplishment which should be seen by further audiences.

Charles Pope Jr.

|