|

Back

Noble Men, Noble Evening New York

Avery Fisher Hall, Lincoln Center

12/11/2014 - & December 12, 13*, 2014

Antonín Dvorák: Piano Concerto in G Minor, opus 33 – Symphony No. 9 in E minor “From the New World”, Opus 95

Martin Helmchen (Piano)

New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Christoph von Dohnányi (Conductor)

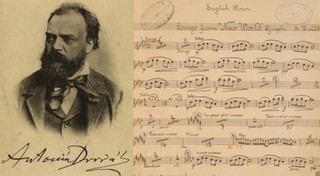

A. Dvorák Ninth Symphony English horn theme original score

(© New York Philharmonic)

A personal adoration for Antonín Dvorák occurred when visiting the “Heroes Cemetery” in Prague several years ago. One wanders amidst cenotaphs 50 feet high, monuments 20 feet wide, epitaphs extolling the epic poems written, fierce battles fought, glorious histories composed...

And then you turn a corner and almost step over a modest tombstone, poking above the ground, reading “A. Dvorák: 1841-1904”

Perhaps a few more words were written. But its modesty was so endearing next to the Brobdingnagian sculptures surrounding the stone, that I knew this man was truly a nobleman.

For this two-week Festival, the Philharmonic had a splendid pictorial exhibition of his work, and the original scores on line at the Levy Levy Digital Archives of the New York Philharmonic, as shown by the picture above.

Through a stupid error, I was unable to reach last week’s concert, when conductor Christoph von Dohnányi was indisposed. This week, not only did the conductor appear in all his eminence–for he is indeed the very picture of the most eminent Central European conductor alive today–but he showed the vigor, the stamina, and the scrupulous care given, for Dvorák’s most popular music.

Even without the knowledge that this German-born 85-year-old master came from the most distinguished family, who led the German resistance, or that he is the grandson of one of Hungary’s greatest composers. One senses, with the stately white mane, the erect stance, the very grace of his movements, that Christoph von lives in a rarefied world, which he evidently wants to communicate to his audiences. Add to this that his grandfather, Ernst von Dohnányi, living almost 90 years, dying in 1960 doubtless worked with Dvorák passing on memories to his grandson.

M. Helmchen (© Courtesy of the Artist)

Yet before he conducted the Dvorák Ninth Symphony, Mr. Dohnányi gave the stage to a pianist 50 years younger than himself for the Dvorák Piano Concerto. Next to the Cello Concerto, this work always seemed inferior, that’s because the Cello Concerto is probably the finest ever written, and the earlier Piano Concerto seems only one of many mid-19th Century virtuoso works.

The original version was almost never played, since the fingering passages were considered to un-pianistic, and even an edited version was left by the sidelines. Some 50 years ago Rudolf Firkusný resurrected both versions, and performed it with care and nobility.

That, though, was not the style for Martin Helmchen. He took the most difficult version (Dvorák’s original) and played it with all the flair, all the fireworks which Dvorák offered. In fact, he took that childishly simple three-note theme, and transformed it into a motoric creation, pressing forward with the agitato part of the first movement without letting up for a moment.

And nobody had to ask where the cadenza was. The whole movement is a cadenza, and this young cherubic German pressed all the right keys. The most bucolic second movement was given more space, up to the last trills. For the humble composer to label the first movement “agitated” and the last con fuoco (with fire) certainly should be a great challenge for any pianist, and Mr. Helmchen gave it every bit of forward vigor, fireworks and muscle-power.

Now, though, it was time for the “New World”, one of the earliest works actually commissioned (and premiered) by the New York Philharmonic itself. Maestro von Dohnányi had changed the shape of the orchestra, putting the cellos and basses to his left. I don’t know what effect it had overall, but sitting in that section of the audience, I was delighted to hear the dark sounds of those instruments for the composer’s wondrous string choirs in the outer movements.

Not only the strings (with a lovely solo by Sheryl Staples), but the brass choir (with only a single blurt on Saturday) played with nobility. Mr. von Dohnányi gave space for English-hornist Pedro Diaz to play his famous solo, and in the great scherzo, allowed winds, brass and the whole ensemble jump along with the greatest merriment.

Today we look askance at the efforts of composers like MacDowell and even Busoni, to bring American Indian and African-American melodies into their music, but Dvorák never made that mistake. He was influenced by both, with Black friends in New York, and seeing the Indians on the Iowa prairies. But he was an original composer, the melodies were his own, and he had that rare gift of offering a true classical symphony which still gives that sound of the open America hinterlands.

Mr. von Dohnányi could have allowed the New York Phil to play almost by rote, but the Maestro leaves nothing to chance. And the result was a warhorse which was still noble and still thrilling. Mr. Dvorák was obviously homesick after three years in America, but his inspiration, as that of the conductor, was never impaired.

Harry Rolnick

|