|

Back

And A Merry Resurrection to You! New York

Alice Tully Hall

12/08/2014 -

Georg Frideric Handel: La Resurrezione, HWV 47

Liv Redpath (Soprano, Angelo), Mary Feminear (Soprano, Santa Maria Maddalena) Avery Amereau (Mezzo-soprano, Santa Maria Cleofe) Nathan Haller (Tenor, San Giovanni Evangelista), Elliott Carlton Hines (Baritone, Lucifero)

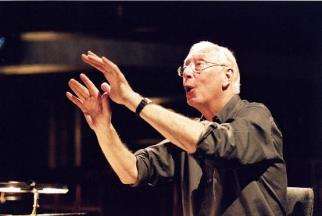

William Hobbs, Kenneth Merrill, David Moody (Singer Preparation), Robert Mealy (Orchestra Preparation), David Paul (Dramatic Consultant), Juilliard 415 Orchestra, William Christie (Conductor)

A Juilliard School Production

W. Christie (© Michel Szabo)

If Bach was the musical heir to massive Gothic architecture and austere Lutheran theology, then Georg Frideric Handel– keyboardist, art collector, painter, drinker, gourmet, businessman, Great Britain’s first immigrant citizen and yes, composer–was the tonal begetter of Renaissance painting, dance and spirit.

Even in this earliest oratorio, La Resurrezione, as produced last night by the Juilliard 415 musical group and their iconic conductor William Christie, Handel showed his colors. Probably in Saxony, he had to hold himself in with instrumental and church works. But once he reached Rome at the frisky age of 22, nothing could restrain his enthusiasm and originality.

The music spoke for itself (see below), but Robert Mealy wrote program notes which almost literally set the stage for the work to follow. Who, save Baroque scholars, knew that the young Handel had been invited to the palace of a virtual Lucullus, introduced to the great foods and wines of Italy? And that he was one of the first composers to be treated as a “gentleman” and not a tradesman. (I don’t agree with that at all: Monteverdi, when he moved to Venice, was equally an entrepreneur and “gentleman” as Handel.)

Who knew that La Resurrezione was given in a great palace, decorated as a theater with a sumptuous buffet for the aristocratic audience?

Who could have guessed that the work was produced with secret stratagems to escape the Pope’s censure? (He thought the soprano was immoral, so Handel substituted a more suitable castrato to please His Holiness.)

And what amateur Baroque-a-phile (like this writer) knew that Handel’s gluttonous benefactor paid for a Bruckner-sized orchestra for the oratorio? (Well, er...Bruckner-sized for 1707: Nearly two-dozen violins, with oboes, recorders, trumpets, more strings, even a bass trombone!)

True, Monteverdi’s opera orchestras (what we know of them) had innovations which only Berlioz later rivaled. But Monteverdi had no precedents and could make up his own rules. Whatever Handel thought of the circumstances, his orchestral imagination was almost liberated. Handel, within the Baroque system, kept the traditional forms, but played around with them to produce a personal brightly-colored Baroque mural.

True, La Resurrezione is no Messiah. Not a single aria can rival the best of Handel’s later oratorios. But within its limited frame, as shown by Juilliard’s splendid performance, Handel used his orchestra not only with freedom but with dazzling innovations.

I think now of the soprano aria “Jesus did not fear”, sung with solo cello, then solo violin and solo oboe, followed by the complete orchestra. An incomparable tapestry. Or the Evangelist John in “Dear Son, dear beloved lord” beginning with a simple basso continuo of harpsichord and theorbo (to which Handel had added his friend, a bass trombonist!) then adding the full orchestra in a series of sforzando chords.

And my favorite, Cleofe’s “Come, let us go now and seek our Beloved.” The tempo is of a jolly gigue (ordinary enough), but it begins with a solo violin playing with the mezzo-soprano, like an Irish jig-fiddler, before adding the orchestra.

Nor does Handel stint on the joy when the two women visit Christ’s tomb and come upon the Angel announcing the resurrection of the Christ. From the beginning, Handel’s overture shouts out a truly happy scene, despite the desolation of the two women here. This continues with an equally elation-filled second sinfonia. The two choruses–sung by the five soloists, as in the original–were as buoyant as could be. The first chorus was used later in the Water Music, the second was simply an elation.

No “Hallelujah” chorus here, but Handel’s inspiration–doubtless helped by great helpings of pastas, truffles, and endless carafes of Italian wine and Italian cheer–was unbounded.

I must confess that each time I’ve tried to buy tickets to William Christie’s group Les Arts Florissants, I’ve been stymied. The tickets sell out immediately. From his very first downbeat here (without a baton, of course), he showed why. The rhythms were swift, dramatic, hardly ever pausing for time.

L. Redpath (© Liv A. Redpath)

That worked well for the Angel and Lucifer–Liv Redpath and baritone Elliott Carlton Hines–whose mastery of Baroque singing seemed, to my amateur ears, right on target. Ms. Redpath’s dizzying passages were tonally perfect, and more important, unlabored. In the quieter passages–and she once gave a pianissimo trill–she was also melodic. Our Lucifer was almost sympathetic in his tirades.

The two women, Mary Feminear and Avery Amereau, started with almost cloying sadness (though again with a brisk tempo), but in the second half, something wonderful happened. When they appeared searching for the tomb, they walked behind the orchestra, until finally coming to the front when seeing the angel. (It was reminiscent of the mini-drama of the Russian Orthodox Easter service.)

I was not terribly happy with Nathan Haller’s hesitant first aria as the Evangelist–but this was solely because it was the first time the music dragged. St. John is not exactly the Fats Waller of the oratorio, though his more plain arias in the second half showed a very rich tenor indeed.

Oh, to have room here for all the soloists of the Juilliard 415 Orchestra. They played their (mostly) period-style instruments with yes, style, But First Violinist Chloe Fedor must get special mention. Not only because her frequent solos were so good, but because she was sitting in the same chair (metaphorically speaking) as Arcangelo Corelli, who apparently was in the original performance.

Handel, in an especially good mood, gave Maddelana the “hit tune” (Robert Mealy’s words) of the oratorio–which came from one of Corelli’s own violin sonatas.

One more word, from Mr. Mealy, which could say why Handel left Germany for less Lutheran posts abroad. In Germany, the intermissions were time for long sermons. In Rome, intermissions were time to eat, drink and be merry. Mr. Handel obviously partook of these savory entr'actes, as did we all for this delicious performance last night.

Harry Rolnick

|