|

Back

08/21/2013

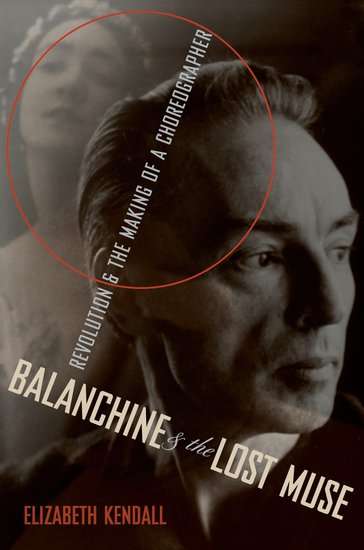

Elizabeth Kendall: Balanchine and the Lost Muse: Revolution and the Making of a Choreographer

Oxford University Press

288 pages; hardcover; photos and illustrations

Dance scholar Elizabeth Kendall pulls the curtain back on the early life and influences of choreographer George Balanchine, the principal architect of modern ballet aesthetic, in Balanchine and the Lost Muse: Revolution & The Making of a Choreographer.

The "lost muse" was ballerina Lidia Ivanova, a gifted and innovative dancer in her own right. She was Balanchine’s first partner in his student days at what were the remnants of the St. Petersburg Imperial Ballet Academy. The school survived, somehow, after the fall of tsarist Russia, in the capital renamed Petrograd, torn apart by war, famine and disease. The young dancers thrived artistically in a harrowing environment.

Balanchine was dumped at the school in 1913 at age nine as his family split up and fled desperate conditions in southern Russia. Balanchine showed much musical talent: he studied piano, doubled as a dance rehearsal pianist, and eventually emerged in productions as a strong caractère dancer.

In the intervening years, the ballet schools and accommodations were halted at various points. On Theater Street, site of the vaunted Mariinsky Theatre, Imperial Theater School, and Petrograd Ballet School, dorms and studios had no heat and food was scarce. Yet the school was a haven for talented students. Kendall rescues this history and the main players in a pivotal artistic time that unfolded in the midst of the Lenin’s 1917 Bolshevik revolution.

Even though Russian ballet had operated under the patronage of the Imperial court, aristocratic patrons and military, after the revolution the doors were flung open and all Russian people were permitted access for the first time. And they embraced the ballet’s artistry lustily, with primal nationalistic pride.

In the years after the revolution, dance artists who had been scattered around Europe, such as Mikhail Fokine and Marius Petipa who were with Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, returned thanks to their love of Russian dance. The ballet, like everything else, was being restructured under the Soviet system.

Meanwhile, there was an artistic revolution within the ballet world and liberation among the dancers and choreographers. They not only wanted to preserve Russian classicism but to reflect the revolution and explore free dance. Isadora Duncan had influenced a generation of Russian dancers when she taught and performed in Russia in 1905-06 and teachers at the school were embracing Duncan theories of free dance (even within pristine classicism) by such influential ballet stars as Olga Preobrazhenskaya, ballet star and Ivanova’s teacher. Balanchine and the other boys were under the laudatory instruction of danseur noble and gifted instructor Samuil Andrianov, who later Balanchine assessed “Made our generation.”

The through line of Balanchine’s relationship with Lidia Ivanova as his choreographic muse is a more sketchy arc in the book, but Kendall gives credible examples of how the specter of Ivanova may have guided Balanchine’s aesthetic, particularly for roles that directly evokes the Russian classicism of his childhood.

Kendall details Ivanova’s technique and beauty onstage which made her very popular with audiences. She was known for her huge jumps and is credited for a creating a fully extended jeté for ballerinas. Her natural athleticism set the standard for Balanchine’s choreographic template for women later. Ivanova was also invested in the bold innovations advancing Russian theater and was challenging the dance theater to adopt similar experimentation. Meanwhile, Balanchine was getting work as a pianist and dancer while also emerging as an important choreographer. In the meantime, he had a series of affairs with women and in 1924 married, Tamara Geva, the first of his many marriages and official muses.

Ivanova was 16 when she was planning to go on tour, a ruse actually to defect in the west with several dancers including Balanchine, but she was killed in a boating incident the night before they were to leave. Kendall dissects the different theories about the dancer’s death, but ultimately, it remains a mystery shrouded in conspiracy theories. Otherwise, Kendall has rescued the almost bio-history of these dance artists with nothing less than heroic scope.

Lewis Whittington

|