|

Back

06/24/2014

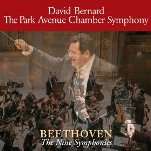

Ludwig van Beethoven: The Nine Symphonies – Concerto for Violin in D major, Opus 61 – Concerto for Piano N° 4 in G major, Opus 58

Susanna Eyton-Jones (Soprano), Jan Wilson (Mezzo-soprano), James Archie Worley (Tenor), Michael Riley (Bass-baritone), David Chan (Violin), Spencer Myer (Piano), Brearley Singers, Central City Choir, New York City Master Chorale, The Park Avenue Chamber Symphony, David Edelson (Concertmaster), David Bernard (Conductor)

Recording: All Saints Church, New York City and Riverside Church, Upper Manhattan (June 2007 [Ninth], November 2008 [Third], February [Fifth], October [Sixth] 2010, May [Eighth], October [Violin Concerto] 2011, May 2012 [Fourth], February 2013 [First, Seventh, Piano Concerto] & 2014 [Second]) – 433’55

Park Avenue Chamber Symphony # PACSNAXOS0030 – Only available in MP3 (download here) or Live Streaming (download here)

Insidiously losing one’s hearing amidst a pining for artistic expression turns our attention to none other than Ludwig van Beethoven: to love Beethoven is to seek deeper understanding inside this cerebral cortex, making one appreciate even more this highly regarded genius. Turn our attention to David Bernard and The Park Avenue Chamber Symphony (PACS) in which the translation is enveloped in thoughtful politesse respectueuse. Importantly, just as “words mean things”, so goes with notes in music. Mr. Bernard succinctly quotes, “To be understood when we speak, the listener needs to hear the space between words and the intonation. We don’t slur our speech and we don’t speak too fast. A performance succeeds when musicians articulate, pace and phrase the music so it is clearly understood by the listener.” This grounded philosophical goal is the reason for Maestro Bernard’s success, seven years in the making. For the sake of brevity, comments for each composition are vestigial in nature.

Symphony Nº 1 in C major, Opus 21 (1799-1800)

The PACS entrées Beethoven’s equation nicely, opening with a well metered “Adagio molto” and fine con brio; the subsequent “Andante cantabile con moto” is very polished, bouncy, not overstated. Brass staccatos are superb. Violins are alive with purpose, Haydnian (even Mozartian) in scope in the closing “Allegro molto e vivace.”

Symphony Nº 2 in D major, Opus 36 (1802)

Maestro Bernard shapes Beethoven’s piece with vibrancy, certainly reflective of the Heilligenstadt Testament: torn emotion seethes within the music filled with hope but agony at the same time. While the “Larghetto” is wrapped in sweetness, The PACS takes off in full drive in a peppy rendition of the “Scherzo”, culminating with bona fide twists and turns in the “Allegro molto.”

Symphony Nº 3 in E-Flat major, “Eroica”, Opus 55 (1804)

Weighted by the second part, The PACS expresses the sobering depths of Beethoven’s demeanor in a soulful rendition of “Marcia funebre, adagio assai.” Solemn in range, the discourse is alerting. The "Scherzo, Allegro vivace” is a dichotomy to the latter, flittering with lightness, but buried inside “heroic” valuation. Maestro Bernard’s “Allegro molto” flourishes with Beethoven’s hopeful good for all mankind.

Symphony Nº 4 in B-Flat major, Opus 60 (1806)

Rather ambiguous in derivation, Symphony N° 4 is particularly well-executed by Bernard & Company: the introductory “Allegro vivace” begins in a rather unhurried clause, quickly indicating that this piece doesn’t bristle with confrontation nor torment as in earlier ones. In the “Adagio” The PACS’ violins sweep away with nicely formed crests and falls, the pizzicati is clean and apportioned. The scherzo-constructed “Allegro vivace” has tinted glances of perkiness; the final “Allegro ma non troppo” brings with it melodious sounds from the woodwinds (oboe and flute) while violins soon commence in complete unison.

Symphony Nº 5 in C minor, Opus 67 (1807)

The familiar four note opening finds Maestro Bernard making the decision to take the tempo rather briskly (as compared to other recordings) which is very good. The horns hold their extended notes beautifully. Clearly, David Bernard knows how he wants to express this piece, and he is undeniably well-connected within Beethoven’s mind. The ensuing “Andante con moto” opens to the beautiful cello section filled with religious atmosphere dialoguing with the mellifluous repartee of the woodwinds. The PACS’ brass is robust and alert shortly after the opening of the “Allegro.” But this track ends tragically without a breath, leaving one in a bit “in the lurch” until it re-opens with the conclusive “Allegro” (Movement #4.) The piccolo has its final say in the closing bars which twinkles ebulliently.

Symphony Nº 6 in F major “Pastoral”, Opus 68 (1808)

This is one of the most interesting pieces within this recording due to the fact that Maestro Bernard sets the opening tempo more slowly than in other recordings. The pacing doesn’t lose any steam, and, perhaps, the decision from the conductor was to savor in the bucolic pleasantries of this particular stretch. It makes perfect sense to do so. Here, the recording decision, by far, is more logical by taking the five movement structure and consolidating it into three tracks (“Allegro”, “Allegro” and “Allegretto”.)

Symphony Nº 7 in A major, Opus 92 (1812)

By this time Beethoven has lost most of his audible connection. That said, this more grandiose symphony elucidates the notion that Beethoven is retaining a positive, hopeful musical jargon: The PACS’ horns pulsate with harmonic majestic value after being prepped by octave slides between the strings and woodwinds. Mr. Bernard creates a concise and vivacious expression. The “Allegretto”, a quasi-variation on a theme, displays stateliness and grandeur that is extrapolated with empathetic reverence. The third movement’s “Presto meno assai” has The PACS retaining nimbleness, bounciness and precision. This is an inherent delight. The summation of Beethoven optimism is profoundly exemplified in the resolving “Allegro con brio” that teems with understated quixotic backtracks and flourishes until the crowning conclusion.

Symphony Noº 8 in F major, Opus 93 (1812)

Maestro Bernard interprets this delightful diminutive discourse with pulsating 3/4 brightness shortly after the opening poignant bars. The insistent “hammering” of sorts, certainly gets the point across that the “Allegro vivace con brio” rhythmically dapples in danse élégante gravitas dotted with pockets of whimsy. The balance of the symphony has frivolous elegance, anchored inside impish charm that David Bernard captures in fine fashion.

Symphony Nº 9 in D minor, Opus 125 (1817-1824)

One of the best selections inside this anthology is the second movement, “Allegro vivace”: here Bernard is on fire. (Recall this was the opening for The NBC Nightly News.) Off to a great start, the apportionment pulsates like a dulled irritant which is actually marvelous. It is a vicious cycle, testy of sorts, but this is how Beethoven would have wanted it. Recall by now no audible feedback is apparent, an important value to keep in mind when listening to this composition. The timpani could very well have signaled the incessant thumping within his deaf eardrum...yearning for clarity, yet indignantly culminating to no meaningful conclusion. David Bernard pounds across this point in a well-delineated construct. Splendidly tempestuous. Not to eclipse the immensity and dramatic values inside the choral structure of the “Allegro assai”, the aforementioned selection is rendered sublime by David Bernard and The PACS.

Concerto for Violin in D major, Opus 61 (1806)

Brief and to the point, David Chan is charming: his “Larghetto” is smooth and well-articulated. The conclusive cadenza will leave one breathless. It is a simple joy to listen to this extraordinary being perform with classical perfection.

Concerto for Piano Nº 4 in G major, Opus 58 (1805-1807)

A showcase piece for any aspiring pianist, Spencer Myer flourishes inside and outside the musical staffs, both treble and bass. His triplets cycle like a well-run machine, yet the emotions are humanly felt. In the “Andante con moto”, Myer is patient to thoughtfully pause. David Bernard has a deep-felt need to not rush the tempo yet not entirely taking the wind out of the sails either. Myer’s pianistic skills in the “Rondo” demonstrate a confident bravado gleam while maintaining a mesmerizing shifting dialogue with the strings. Myer has a sophisticated energy that can be likened to a stately Rolls-Royce.

Since the album is a live recording, most extraneous noises (i.e. sneezing, coughing) are kept to a minimum. Sound quality is extremely good, but “finishes” for each of the tracks are rather inconsistent: some have an instant cut-off which comes across as disruptive while others continue with applause for an extended period. It would have been nice to see more uniformity such as gradual fades to create consistency. In a couple of places two movements would have been better served as a combination in order to avert abruptness in pacing. Case in point: linking of the “Larghetto” and the “Rondo” in the Violin Concerto in D major and the last two movements (the two “Allegros”) of Symphony Nº 5. Though miniscule points, this doesn’t detract from the umbrella of aesthetics.

Several days ago it was announced that Maestro Bernard was selected as one of the semi-finalists in the “The Community Orchestra Division” for The American Prize in Conducting. It is apparent that The PACS has worked hard in reaching this honor and distinguished nomination. We wish David Bernard and The PACS our best for a successful outcome.

Christie Grimstad

|