|

Back

06/08/2014

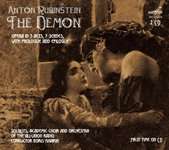

Anton Rubinstein: The Demon

Alexander Polyakov (The Demon), Nina Lebedeva (Tamara), Evgeny Vladimirov (Gudal), Alexy Usmanov (Prince Sinodal), Nina Grigorieva (Nanny), Nina Derbina (Angel), Yury Elnikov (Messenger), Boris Morozov (Old Servant), Academic Choir of the USSR All-Union Radio, Klavdy Ptitsa (Artistic Director), Symphony Orchestra of the USSR All-Union Radio, Boris Khaikin (Conductor)

Recorded in 1974 – 147’51

Firma Melodia # 10 02102 – Booklet in English, French and Russian

Anton Rubinstein is best remembered by his virtuosic mastery of the piano, but he also was prolific in the genre of opera. Within his life span he composed 20 operas, and he is best remembered by his 1875 premiere of The Demon. Rubinstein unfortunately had an uphill battle his entire life, himself proclaiming in a notebook journal, “…My conclusion is that I am neither fish nor fowl – I am a pitiful individual.” Pitiful indeed that he thought of himself in this manner since he contributed much to classical music by way of composition, conducting and the creation of music conservatorships.

The Demon, a fantastic opera in three acts (with Prologue, Epilogue and Apotheosis), was warmly received by the public, including his nemesis, “The Five”, a collective Russian nationalism force spearheaded by Mily Balakirev. Ignacy Jan Paderewski was direct enough in saying that Rubinstein “had not the necessary concentration of patience for a composer.” There is a bit of truth in these words for The Demon, despite the immediate accolades it received at the time of its debut, does have patches of unevenness in scoring and the characterizations of the protagonists (i.e. The Demon and Tamara) are a tad shallow. That said, it is still a rare treat to have the restoration of this 1974 recording released for the first time ever under the Firma Melodia label. Listeners who are open to venture beyond the expected Russian operatic canon will want to look into this generational “first.”

Based upon Mikhail Lermontov’s poem (the “oriental tale”), Rubinstein’s music is heavy and deepened to the core. Though the “Introduction” provides us with ominous threads, the pursuant choral repartee from the women’s chorus shines with hopeful brightness, Rubinstein’s more Westernized strains emanating with reminisces to Gounod’s Faust (1859). Alexander Polyakov soon follows in his “Monologue” that’s beautifully resolute, his voice likened to a light-timbre Boris Christoff. A bit of obscure Faust haunts the sidelines, but there’s even more energy and emotional anger tied to Rubinstein’s character than that of Gounod’s.

Nina Lebedeva’s (Tamara) aria, fluttering around the maids’ chorus, has woodwinds making their entrée mark, the 2/4 metering with chirping woodwinds which closely resembles Amalia’s eh voilà , “Lo sguardo avea degli angeli” from Verdi’s I masnadieri (1847.) Lebedeva’s voice has a clarion sheen yet a bit of steel edging as well. The music is very Puritanical and innocent with Lebedeva smoothly running through octave jumps in the end. Her Nanny (Nina Grigorieva) radiates with a tone of stability and mellowness that will instantly connect with Filippevna from Eugene Onegin (1879.) The ensuing “Trio” involving the Demon, Tamara and the Nanny is compounded by melodic and angelic sweeps, accompanied by beautiful runs on the harp.

Rubinstein’s Caucasus elements are first revealed during the “Hey! Hey!” (Prince Sinodal and the Servant) and continue with Alexy Usmanov’s “Romance.” Usmanov is disciplined with excellent voice control and wholeness in tonality. The voice sits tightly and comfortably within Rubinstein’s notes.

The bit of frivolity (if one were to call it that) lands within the opening of Act II. The men’s section of the Academic Choir of the USSR (The “Toast Chorus”) has magnificent blending and choral stateliness, bringing to mind Thomas’ section in Hamlet (1868.)

There’s some tricky, capricious pacing in “The men’s dance” simmering in pulsating visions and Eurasian steppe aural élan. The celebration continues with "The women's dance" containing subtle verves to Borodin’s Polovtsian Dances. This soon leads into the mounting “Romances” (First and Second) that The Demon sings, adding imminent climax to the forthcoming “Apotheosis.” One will hear a preponderant echo which gives Polyakov's singing a mesmerizing and intoxicating effect. The chorus of the Nuns (“The one who creates everything, the one who is eternally good") is simply gorgeous and brings with it a sense of anticipatory calm.

The Demon has many stupendous moments, but there is something of a disconnect in the music: it parses down to being a string of musical numbers, and its remains are musically fallow. Devoid of any true memorable numbers, Rubinstein’s work is still to be commended. The recording is clear, has a bit of echo and is chintzy on the bass. But now titled with “the only recording in town”, one simply can’t quibble.

Christie Grimstad

|