|

Back

Soaring Sounds of Sea and Space New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

05/06/2014 -

“Spring For Music” Presents:

John Luther Adams: Become Ocean (New York Premiere)

Edgard Varèse: Déserts

Claude Debussy: La Mer

Seattle Symphony, Ludovic Morlot (Conductor/Music Director)

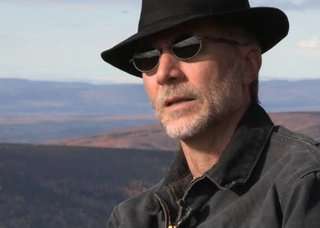

J.L. Adams (© Courtesy of the composer)

“Life on this earth first emerged from the sea. As the polar ice melts and sea level rises, we humans find ourselves facing the prospect that once again we may quite literally become oceans.” John Luther Adams

That comment, in the score of John Luther Adams’ Become Ocean, was far more despondent than the sonic waterscape he painted last night. But coming five-billion years after the earth was formed, and 24 hours after President Obama warned (in a pallid shortsighted quote), that “climate change is affecting Americans right now”, Mr. Adams work was a prescient reminder. A reminder that 70 percent of our world is ocean. And its mightiness, its torrents, it waves, placidity and storms are generated by infinitely more powers than the greatest scientist can imagine.

The Seattle Symphony commissioned Mr. Luther for this music, last year, it won the Pulitzer Prize, and its premiere here last night from the visiting orchestra showed that it is a singular work from a most singular composer. Mr. Adams, originally from Mississippi is now a resident of Alaska, perhaps the only famed musician (outside of Jewel, who moved away) to live there. As environmentalist, he has tried to picture his world and his nature. But in Become Ocean, he has finally surrendered and tried to actually “become” in music what he has actually seen.

In a certain way, Mr. Adams’ work was not so different than the piece which finished the program, Debussy’s La Mer, written 110 years before. Both of them tried to picture the movements of the ocean, both of them precluded even the idea of human (or piscatorial) movements, both of them were sheer energy.

Nor did either of them ever approach basic musical forms. Like the waves themselves, the climaxes, emotional not musical highs, and quickly went down to their own troughs. Both of them used energy as the propelling force. Neither of them used actual themes. Both were revolutionary.

Mr. Adams’ Become Ocean (the title comes John Cage) did have a form, that of a giant palindrome. But I doubt if many in the audience were aware of that, including myself. I felt that the different sectors of the orchestra, moving at different tempos, had gone from the softest rumblings to a series of highs and back again, but not until reading a piece by the New Yorker’s Alex Ross did I realized that Mr. Adams had literally gone backwards from the middle.

But this was unimportant, compared to the series of velocities, the varieties of harmonies (quite consonant), the pulsing, throbbing colors of the entire orchestra.

I was not bored by these changing colors, but was intrigued at Mr. Adams’ mastery, how he managed to create an entire easel of flows and ebbs, of tremors and undulations. That the work did have a time measurement of 42 minutes was almost irrelevant, because time quite literally disappeared. In a work like this, some in the full-house mainstream audience would be surreptitiously glancing at their watches, but nobody even thought about that. In eternity, time is a non-starter.

The repetitions by pianist, strings, percussion, brass and winds, might have seemed monotonous to us watching from the auditorium, and conductor Ludovic Morlot was perhaps restricted to beating a kind of modified series of rhythms. But I doubt if either of them were bored. Neither the orchestra, conductor or audience ever quite “became ocean”, but we were each in our way part of Mr. Adams’ segment of universal endless time.

Perhaps the major difference between Become Ocean and La Mer was that Mr. Adams tried to transform ourselves into nature. Debussy, by using the frozen stylized wave of Hokusai on the cover of his score, showed that his sea was a figment of his artistic imagination.

L. Morlot (© Sussie Ahlburg)

But it still was a dazzling performance by an orchestra which was founded exactly the same year that Debussy had written his score. La Mer played no palindromic tricks on the audience. Indeed, Mr. Morlot had a particularly intuitive projection of the music. This was not the music of sweep and enthrallment, but of color and freshness, and the final horn announcement of the chorale was almost a white-hot clarion call. (With even more red-hot music from a Debussy encore.)

Alas, in an otherwise electrifying performance of the Varèse Déserts, the French horn fluffed a few notes. But this hardly detracted from a work which must be heard live on a large concert stage. The four winds, ten brasses, the massive percussion (with the largest bass drum I’ve ever seen!) and piano were spread out over the Carnegie Hall stage, without any of the Varèse pre-recorded tape to interrupt the sound of pure music.

The few errors were minuscule compared to the waves of music sweeping across the stage. While this was meant as a tribute to these splendid players of the Seattle Symphony, Mr. Morlot again gave that sense of impetus and sheer momentum to the piece.

If John Luther Adams plumbed the spaces of the ocean, if Debussy had surveyed the infinite colors of the sea, Varèse seemed to say, “Let’s restrict ourselves to a few dozen yards on stage and see how we can turn that into an infinity of pure sound.”

It was a sound decision for an extraordinarily spatial occasion.

Harry Rolnick

|