|

Back

A Pair of Cosmic Visions New York

Avery Fisher Hall, Lincoln Center

03/27/2014 - & March 28, 29, 2014

Claude Vivier: Orion

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 9 in D Minor (Edition Nowak)

New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Manfred Honeck (Conductor)

M. Honeck (© Felix Broede)

Manfred Honeck. the last-minute substitute for Gustavo Dudamel, has a mighty handful of challenges this weekend.

First, he has to lure an irrationally picky audience into Avery Fisher Hall. Irrational, because Mr. Dudamel, whatever his talents, has become an Icon, a Brand. Mr. Honeck, merely an excellent conductor, the Music Director of the Pittsburgh Philharmonic, had no full house last night, and it’s questionable whether he can lure them in for two more performances.

Second was that Mr. Honeck is not Gustavo Dudamel, nor does he have that ambition. He is certainly a dynamic conductor, and his last appearance with the Philharmonic last year was an exciting one. Expressive as he was then, one would have thought that Bruckner, from his native Austria, would be in the same class. But Anton Bruckner does not lead itself to that kind of physical excitement which Mr. Honeck produced with Grieg and Beethoven’s Seventh.

He might be good, one thought, but Dudamel, had he been overly idiosyncratic would have produced a singular Ninth Symphony. Phil audiences lap that stuff up.

The third challenge was almost insurmountable. Mr. Honeck’s program contained the two most unlikely pair of composers since, say, Palestrina and Fats Waller. With no intermission, would audiences really relish Claude Vivier and Bruckner?

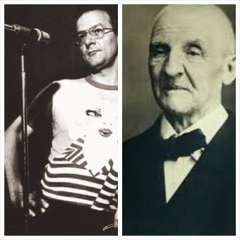

C. Vivier, A.Bruckner

(© Réunion de la Ligue canadienne des compositeurs, Windsor/Commons.wikipedia.org)

True, both composers were eccentric in their own ways. After that...well, Bruckner hated to leave his Austrian town, hated traveling, was a modest organ-player, was stolidly Catholic and died peacefully while finishing last night’s symphony.

Claude Vivier, born in Montreal, never knew his parents, was a happy homosexual, described his music as plainly sexual, had insatiable wanderlust, moving from Bali to Japan, to Morocco to Malaysia, back to Canada, over to Paris, where he had studied with Stockhausen. (And while the German admired the Canadian, he stayed physically away, since Vivier never took off his jacket, which was...er...pungent.)

In Paris, Vivier was knifed to death by a male prostitute at the age of 34–while composing a piece about a man being knifed to death by a male prostitute.

His life story, in other words, makes Berg’s Lulu sound like The Sound of Music.

Musically, of course, they had nothing in common, but Maestro Hornick did his level best to make Vivier’s 15-minute Orion as brilliant as the composer could make it. And, like Vivier, it was wild, multifaceted, and at very first hearing, almost delectable.

It starts with a trumpet melody, it continues with flourishes in the orchestra, then back to the trumpet, and now goes on a merry-go-round of its own. In the middle, the percussion plays some very authentic Balinese gamelan music (more bona fide than Benjamin Britten’s attempts), the solo trumpet calls are reminiscent of Ives’ The Unanswered Question, but the scurrying orchestra and mad solos from horns, trombones and drums make up the cake for which there are decorations.

The end is actually a series of faux-endings, but they all hinge upon–surprise!!–harmonies which come out of Ars Nova religious music. Vivier was a lapsed Catholic, but never rejected the esoteric mystical side of the Church.

Orion hung together thanks to that trumpet tune. But I would need a second hearing to actually dig myself into the manic enjoyment which Vivier must have had in composing it. The New York Phil sounded like they enjoyed it too, though in the supposed simultaneous orchestral climaxes, the orchestra was rather ragged, perhaps denying an unalloyed joy.

The Bruckner Ninth was given the standard treatment of abstruse, complex, meaningless revisions by various students (approved by the composer), a reversion to the original (with more revisions by Ferdinand Löwe), and that score revised by Alfred Orel, which was then re-edited by Leopold Nowak. (And the program notes describe this as “easier than most of his symphonies.”)

To add to the confusion, an excellent continuation from his 200-odd bar unfinished finale has been composed, though this is rarely used. In fact, Mr. Honeck was happy to conduct the first three movements with competence, a few exaggerations and a moderate reception.

The first movement was suitably mysterious, never pushed forward, and never played with any excess of pulse or meter, although Mr. Honeck did give very very long pauses. The finale was, like the opening, played directly, plainly, but the final horn parts, the last notes of a movement which Bruckner ever wrote, never achieved that so celestial sounds.

Where Mr. Honeck did make an effect was the Scherzo, which was absolutely terrifying. Whatever moderation he conducted in the outer movements, here he suddenly came to life and allowed the Phil an almost demonic sound.

After the concert, I was asked what I thought Claude Vivier’s music would have sounded like if he had lived more than 34 years. It’s a useless question, of course, but one would like to think that he would have continued with that brilliant technique in orchestra and piano music, thrusting himself into the musical cosmos.

On the other hand, he might have had a revelation and composed in a style merging Fats Waller and Palestrina. His own thoughts on the matter are thankfully tacit.

Harry Rolnick

|