|

Back

Mr. Penderecki’s Planet New York

Zankel Hall, Carnegie Hall

03/20/2014 -

Krzysztof Penderecki: Duo Concertante – Suite for Solo Cello – Sextet – Sinfonietta per archi – Sinfonietta No. 3

Eunice Kim, Luosha Fang (Violins), Born Lau (Viola), Tessa Seymour, Arlen Hlusko (Cellos), Robin Kesselman (Double Bass), Stanislav Chernyshev (Clarinet), Dana Cullen (Horn), George Xiaoyuan Fu (Piano)

Curtis 20/21 Chamber Orchestra, Krzysztof Penderecki (Conductor)

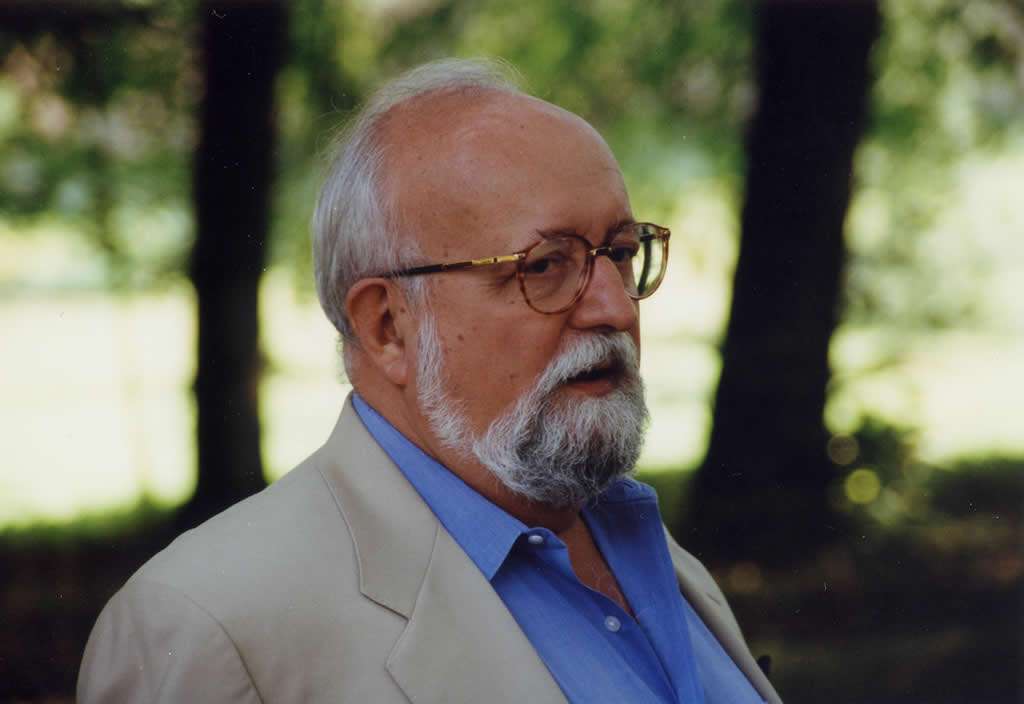

K. Penderecki (© P. Anderson)

Call it a serious case of Ageism. On one side of Carnegie Hall, the over-40’s group, the Great, the Good and the Elegant, bejeweled and bespoke-suited, crowded in to hear Mehta, Zukerman, and the Israel Philharmonic play another (sigh) Brahms, another (yawn) Tchaikovsky. Nothing wrong with that, except...

Except that on the other side of the wall, down in Zankel Hall, the under-40’s student group, sans cravates, but plenty of tablets, Ipods, musical scores and rapt enthusiasm, watched one of the most celebrated iconic composers of the past 40 years as he conducted, watched and obviously relished his music played by virtuosi of Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute.

It was not a packed house (New Yorkers are artistically as conservative as Nebraskans), but the audience embraced the music like young lovers. Amongst the rare older folk here were a critic or two, and of course Krzysztof Penderecki, the Master of his Universe, born ten years after the founding of Curtis Institute 90 years ago, but ever more youthful when he took to the podium for the final half of this extraordinary concert.

Mr. Penderecki has become one of New York’s more familiar figures this past year, with talks, concerts, and informal conferences. As immaculate in his dark suit as his music, bearded, eyes twinkling, a thinner Santa Claus, the composer bestows his gifts where’er he goes. And we (not the bejeweled Great and Good) are all the better for it.

On the podium, he is still the young conductor. Mr. Penderecki needed neither seat nor baton, but he conducted like a neophyte at a heavy audition. The Curtis Institute players are quite brilliant in their singularity, but he molded them into an ensemble with gestures, cuing, movements which broadened the color of his own pieces.

Actually, his two ensemble works were transcriptions of his own chamber music, so both, even the American premiere, had a certain familiarity. That, in fact, was the Third Sinfonietta, taken from his own Third String Quartet. And that incredibly personal work was played in front of the composer a few months ago at Symphony Space.

The transcription job was masterly, for Mr. Penderecki is a string virtuoso, and he lets nothing go by chance. Where in the Quartet, he let the individual instruments pursue their different motifs, here the mournful solo viola led the entire ensemble into his strange personal (it’s called “Leaves from an Unwritten Diary”) universe. What I was waiting for, after the first 14 minutes, was, after a nocturne and a waltz, a tune which dated back to an earlier era. I had imagined it to be a tune from the shtetl or a Roma (gypsy) warble. But Penderecki had described it as a tune which his violinist father had played, probably from Rumania. It was unsettling–similar to the composer’s sudden change to 14th Century music in his Passion.

Before that was a reworking of the String Trio, with the hammering chords as a motive, an idée fixe for the orchestra. It is called a “symphony for strings, but this is far more a concerto grosso, with the solo violin, viola and cello playing against the entire ensemble.

One doesn’t realize the intense mastery of this composer until a fugue towards the end. A fake fugue, for it starts and then disappears into a massive amalgam of contrapuntal chaos, a ferocious ending.

It says something about the composer’s gentility that, after the Sinfonietta, he proceeded to shake the hands of every member of the Curtis Ensemble. He is a modest person, but one had little doubt that he enjoyed being in the spotlight with such talented young players from so many different countries.

For the first half, the composer had taken his place in the balcony, while a group of amazing young soloists performed his chamber music. And I don’t use the word “amazing” lightly. For Mr. Penderecki earlier this year had told an audience that he does not make things easy for his players. He exercises them–vocalists, orchestras and soloists–to the limits of their instruments and their possibilities.

Listening to these first three pieces, I felt he had a kinship with the late Elliott Carter. Not in technique or language, but because both composers in their chamber music would take up an original musical challenge and compose to meet and vanquish the challenge, almost as a game.

What else could one say about the opening Duo Concertante, for violin and double bass? The idea came from Anne-Sophie Mutter two years ago, and Mr. Penderecki wrote it–but may have fudged the dare. After all, he lifted the double bass a whole tone higher, as did Mahler in his Fourth Symphony. But where Mahler was looking for a demonic sound, Penderecki was simply trying to give a lighter, higher feel for the double bass in order to complement the violin.

“With a three-octave difference between the instruments, he bass has to play fairly high.”

(On the other hand, perhaps the violin could have played fairly low, though violinist Penderecki probably didn’t wish to sacrifice that sound.)

The result was not quirky or ironic or amusing. But was a good duet with a full share of triple-stops, triple-stop glissandi, snaps and bangs on the double-bass (with hand and knee) and a delightful jaunt for them both.

The following Cello Suite had all eight sections of the Baroque suite. Again, this was such a demanding piece that Tessa Seymour, on stage alone, seemed to occupy all of Zankel Hall. I have only one bone to pick. The fifth movement is labeled Allegro con bravura. “Bravura”, though, describes it all, with eight evocative moods (including a most un-Straussian “Valse”).

The last work before the orchestral sections, was the Sextet, which has been played here no less than three times in the past year. On this third hearing, I couldn’t say I heard more than before, but this group played it with more youthful energy than I had heard before. At that time I compared it to a Chagall painting, with frenzied dances, desolate and joyful quotes.

And I can do no better than rewrite myself on Penderecki himself in this concert. “...a man whose mind embraces the sacred, the quirky, the forests and meadows, the forms of the past, the techniques of today, and the serpents, angels, hells and Edens of our minds.”

Harry Rolnick

|