|

Back

Liturgical Celebration, Laud and Clear New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

03/06/2014 -

Ludwig van Beethoven: Missa Solemnis, opus 123

Susan Gritton (Soprano), Julie Boulianne (Mezzo-soprano), Michael Schade (Tenor), Nathan Berg (Bass-baritone)

Oratorio Society of New York, Kent Tritle (Music Director), Orchestra of St. Luke’s, Sir Roger Norrington (Conductor)

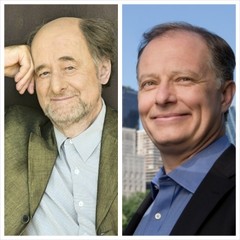

Sir R. Norrington, K. Tritle (© Manfred Esser/Jennifer Taylor)

With utmost temerity did I enter Carnegie Hall to hear Sir Roger Norrington conduct Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis last night. Sir Roger, the pioneer of “authentic” Olde Musicke, Sir Roger, never afraid to pare down mighty forces to give historical verisimilitude to familiar blockbusters.

What would he do with Beethoven’s single mightiest creation? Bring us eight singers and a chamber orchestra? Give the soprano part to a boy with short leggings?

Not to worry. In his 50 years as a stellar conductor, the eighty-year-old Maestro has led every kind and size of ensemble. And here, he hardly stinted on his forces. Yes, the 60-piece Orchestra of St. Luke’s was not exactly Brobdingnagian, but their sounds rang out well enough. Yet behind them, the 136-year-old New York Oratorio Society, led by Kent Tritle, had the kind of forces which would have satisfied a 1907 Elgar oratorio. I counted 200 voices in the program listing, and stopped when I had only gotten to the middle of the basses.

The essential thing was how Sir Roger, still elvish, delightful, humorous, giving a little wave to late-comers after the Kyrie, would handle this legion of singers.

One could only say, provisionally, that there was nothing “Austrian” in Kent Tritle’s New York Oratorio Society for this alleged Vienna Festival contribution. The chorus responded with electrifying alacrity. Their fugues were spot on, the melodies rang out without a murmur, they responded to the sitting Sir Roger like a shotgun–or like a Von Karajan chorus.

The result was a grandiose Missa Solemnis, not terribly solemn but certainly possessing the grandeur which Beethoven would have loved. True enough, such a stark 90 minutes of hallelujahs and amens could have a tendency to sound monotonous But Sir Roger, ever the genial controversial conductor, altered tempos, gave the most spiritual respite to solo violin and flute–”and the spirit of God moves upon the waters”– and happily lashed his groups into a euphoric totality.

(Total except those last four measures. What on earth–or in Heaven, since God realized that Beethoven’s creation was a lot more creative than His–prompted Beethoven to write such a boring ho-hum ending?)

Yes, the opening Kyrie seemed on the slow side. Beethoven called for it to be “sustained”, but Sir Roger held back his forces like steeds at the Kentucky Derby starting gate. After this, the chorus ran ahead, pumping, throbbing, and playing demonically difficult intervals and high tones (the sopranos starting a fugue on a high B-flat was impossible in Beethoven’s day and is difficult even today.)

St. Luke’s Orchestra (St. Luke was too busy writing his Gospel to actually found the orchestra, but they did begin in his church four decades ago) did not actually lag behind, and in other circumstances would have been satisfactory. Here, though, the lack of absolutely perfect stops and starts did seem a little awkward compared to the chorus.

M. Schade, S. Gritton (© Harald Hoffmann/Tim Cantrell)

Sir Roger did not place his soloists to the front of the proscenium. Instead, they were situated just in front of the chorus, a virtual Primus inter pares. Since the four have relatively few solo pieces, but interweave with the chorus, this made sense.

In their ensemble work, they were one organism. As soloists, they were lovely–Ms. Gritton strained as little as possible during the high Sanctus, tenor Michael Schade was appealingly lyrical, and Julie Boulianne and Nathan Berg blended in nicely.

On the other hand, what choice do the soloists have here but to sing as clearly, as resonantly and as enthusiastically as possible? Beethoven, from what we know, wrote this to please himself and his own inner ear. And to hell with making those singers feel comfortable with themselves.

Yes, Beethoven flogged them around, and Sir Roger Norrington restrained them as much as possible. The result was a rousing Mass, not a religious one. It was not so much sacred as insistent, not so much holy as whole-hearted. But in our secular world, in the secular confines of Carnegie Hall, that is probably sufficient.

Finally a message for Sir Roger himself, quoting from the Gloria: Gratias agimus tibi propter magnam gloriam tuam: “Thanks a whole lot for thy great glory.”

Harry Rolnick

|