|

Back

Comfort, Joy, And Discomfort New York

Avery Fisher Hall, Lincoln Center

12/05/2013 - & December 6, 7, 2013

Thomas Adès: Three Studies from Couperin

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 18 in B-flat, K. 456

Felix Mendelssohn: Symphony No. 3 (“Scottish”), opus 56

Richard Goode (Pianist)

New York Philharmonic Orchestra, David Zinman (Conductor)

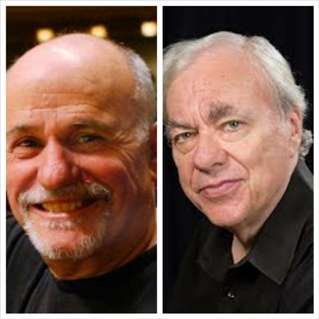

D. Zinman/R. Goode (© www.davidzinman.com/Michael Wilson)

Not only did the New York Philharmonic Orchestra run the whole abecedarian gamut from Adès to Zinman last night, but they twice squared the circle. First by playing music from four centuries in three pieces. Second, in the same musical trio, performing music from five different countries.

The distinguished soloist, though, played a single work from a single century. Richard Goode playing Mozart’s exquisite 18th Piano Concerto, was an essay in the most crystalline music, performed with affection.

Historically the jury is still out on whether Mozart’s work was actually written for the famed Maria Theresia Paradis. Ms. Paradis was blind from birth, but if Mozart did write this for her, she must have been at least a brilliant technician. For the soloist has to roam up and down the keyboard without stop. Torrents of notes from top to bottom, infinite sparkling arpeggios, trills, fountains of notes from start to finish.

It also seems to me that Mozart had to have been writing for a woman, since the 18th Century conception of the female was to be decorous, pretty and hopefully efficient. In this work, one does hear the listen to technically difficult, very pretty and certainly decorous music, with only rare glimpses for what we consider pathos or profundity.

Mr. Goode must have played this many times, but by bringing the score to the piano, he gave an impression of first-time enthusiasm. And yes, he brought that enthusiasm to all the runs, he shaped them not with architecture solidity but a fluid invention. When he ascended a few times with 32nd note-speed and descended playing in thirds, one could picture this played by a modest woman, not a stalwart man.

The tempos worked out by Mr. Goode and conductor David Zinman were a bit faster than usual, even in the second movement. Whether Mozart intended this for sheer external pleasure or not, even the wistful minor-key slow movement variations were given a playfulness, as if Mr. Goode was saying, “Why bother to plumb the depths, when we can all enjoy 30-minutes of sheer joy?”

American-born David Zinman made a name for himself in Europe, where he still conducts some of the best orchestras on the Continent. When he does make rare visits here, he shows experience, competence and the best of taste. Which more or less describes Felix Mendelssohn himself.

I confess that by coincidence I had been reading Richard Wagner’s long essay on conducting yesterday afternoon, especially his evident “praising with more than evident damns” the music of Mendelssohn. Wagner was hardly a subtle prose writer, so his contempt for that composer was barely hidden.

Still, Mendelssohn’s final symphony, based on his painter-like love for Scotland, has an ease, a comfort, and yes, a Hibernian swing which is undoubted. So competent is this (in the best sense), that Mr. Zinman let the NY Phil allowed the music to swing along. Some beautiful clarinet solos, and the triumphal brass chorale at the end made the “Scottish” Symphony, like the preceding Mozart, give in this holiday season, comfort and joy.

F. Couperin/T. Adès

(© Anonymous, Collection of the Château de Versailles/Faber Publishers)

That same comfort and joy was not to be had in the challenging–and very disconcerting– opening work, Thomas Adès Three Studies from Couperin.

The preposition says it all, for the prodigious and always inventive Mr. Adès took what he wanted from his beloved François Couperin harpsichord work and plumbed that razor-sharp line between orchestrating (with two chamber string groups and the usual winds, brass and percussion) and tranfiguring the mood.

The opening Les Amusemens was far from amusing. The bass and alto flutes, the cellos, the low strings were almost somber, almost ominous, the rhythms didn’t quite seem to jibe, it left us all just a wee bit rattled, as if Adès wanted to prove that Couperin was anything but a “nice composer.”

The middle work, Les Tours de Passe-passe (Sleight-of-hand) was most discomfiting of all. The original harpsichord piece is a jaunty song obviously about a street charlatan. Mr. Adès changed that by changing those triplet rhythms almost by the measure, by adding some (clairvoyant?) taps and swells of the strings, ending with a resounding whoop.

With the third, L’Ame-en-peine “The soul in distress”, David Zinman missed a rare opportunity. At first, it might have seemed cheap to dedicate the work to the memory of Nelson Mandela, who had died a few hours before. But this music, with its minor-key lugubrious sighing, its funereal lines, its emotional underpinning and–most of all–its muffled drums, the very symbol of a funeral procession, were as appropriate as any music could possibly be.

Anyhow, when I heard Mr. Adès’ transcription, far sadder than the original, my mind went off the music to that late great leader. I doubt if Mr. Adès would have minded. Mr. Zinman pulled out all the stops with the Philharmonic strings, and the drums were a virtual oratory on the death of Mr. Mandela himself.

Harry Rolnick

|